Winston-Salem is a city that cares about its history, as Mayor Allen Joines noted during the May 14 unveiling of a historic marker to commemorate Five Row. He might have added that the city’s reverence for history sometimes amounts to memorializing what’s been lost rather than sustaining what has value.

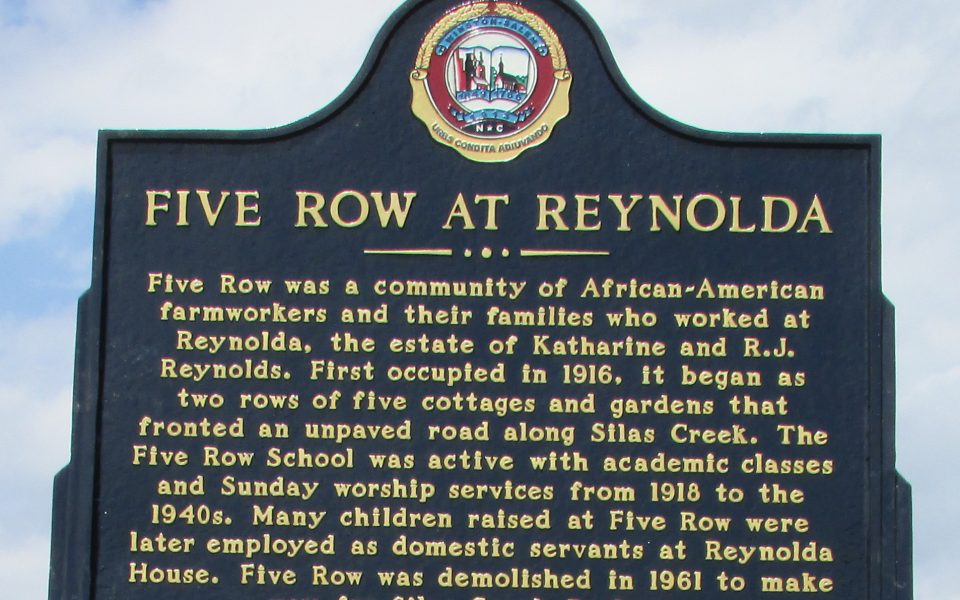

The community was home to the African-American workers who helped build and maintain Reynolda, the early 20th Century country estate of the Reynolds tobacco family.

Segregation, which had been well established for almost two decades by force of law and custom by the time the Reynolds family took up residence in 1917, decreed separate and parallel communities for the white and black workers that supported the estate.

The American Country House movement, of which Reynolda became an exemplar, emphasized self-sufficiency and healthy, country living. It was in many ways a reaction against the industrialization that created the wealth to make these utopias possible. The working farm and landscape gardens at Reynolda employed a brigade of dairy farmers and horticulturists, providing the economic basis for Reynolda Village, whose residents were exclusively white, with the exception of Katharine Reynolds’ major domo and chauffeur, according to the official history of the estate.

Black workers, who mowed, drove, hauled, cleaned and trimmed the estate according to a new photo journal produced by Reynolda House Museum of American Art and Peppercorn Children’s Theatre, were housed in a separate community down a dirt road on the banks of Silas Creek. Both Reynolda Village and Five Row had their own schools.

Compounding the initial insult of segregation — the implication that blacks must be inferior by the requirement of separation — the aftermath only poured salt in the wounds by treating the black community as an aspect of Reynolda’s history that should be erased to cover up the embarrassment of institutional injustice.

While developers and preservationists saw fit to retain the handsome, English-style white buildings of Reynolda Village and give them new life as a retail center — a Chinese dumpling shop, bistro, salons, yoga studio and restaurants currently inhabit the complex — the separate black community along Silas Creek was treated as an impediment to progress. The community was demolished in 1961 to make way for the new Silas Creek Parkway, which connects Wake Forest University to Hanes Mall, and enabled the development of affluent, new subdivisions on the west side of the city.

Gigi Parent, an administrator at Wake Forest University who has researched Five Row, described a modest, but well-loved community of 10 houses, five on either side of the road, along with a church and schoolhouse.

“All the houses had four rooms, a kitchen and a wood stove,” Parent said. “They had a screened front porch, wood floors and ceilings, and they were painted white. There was no electricity or plumbing in Five Row. They used gas lamps, and they had an outhouse.

“There was a dirt road down the middle, but the houses were lined with hedges and lawns,” she continued during her remarks before the marker unveiling. “Each of the houses had a flower or a vegetable garden — most had both. There were awards given for the best flower garden by Mrs. Reynolds, when she was alive.”

Perhaps the rarified atmosphere of Reynolda, as a model farm and a world set apart from the industrial behemoth Reynolds’ tobacco works, allowed the black residents to take advantage of professional opportunities that were other otherwise denied in the larger Jim Crow society. Parent recounted that when Katharine Reynolds discovered that her maid, Lovey Eaton, held a college degree and had worked as a teacher, the lady of the estate said, “I can get another maid; you’re going to be the principal of the school.”

Also unique for the time, Parent said the students in Five Row used the same textbooks as the white students at Reynolda Village School. Five Row School, which at its height served 60 students, ran eight months a year, in contrast to the six-month calendar used by the public schools at the time. The school held a stellar reputation, Parent said.

Subjects of study included history, geography, spelling, arithmetic, the Palmer writing method, health and hygiene, art and music. The students performed operettas for audiences that included Katharine Reynolds, and produced plays using scripts from New York that would have been considered novel in Winston-Salem for any school, black or white.

It’s hard to comprehend how 50 years ago city planners determined that such a community wasn’t worthy of preservation, or maybe it was virtually invisible. The fate of Five Row raises the question of what communities today might be undervalued, invisible and at risk of erasure.

While the destruction of Five Row cannot be undone, the community and its descendants have now finally received a long overdue recognition.

Reflecting on the experience of walking from Wake Forest University to Reynolda, Parent laid out a vision.

“I can see the men and women who worked in the woods when I walk on the paths,” she said. “This marker will allow me to see the houses, the gardens, the school and the church, the boarding house where multiple families and the school teacher lived.”

She choked up with emotion.

“They were here,” Parent said. “They were important. They made this community. They deserve this.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply