Hundreds of men and women brandishing torches while shouting, “You will not replace us,” flash across the screen as viewers watch in dead silence. A silver Dodge Challenger drives into a group of protesters, killing one Heather Heyer, reminding viewers of how far we have not come.

We’ve seen it all before.

Only this time, the scenes don’t play out on a smartphone or laptop or TV screen; they carry a new kind of weight as the coda of Spike Lee’s latest film, BlacKkKlansman, in movie theaters across the country. The movie, which debuted on Aug. 10, marked the one-year anniversary of the events in Charlottesville and chronicles the real-life story of how Ron Stallworth, the first black police officer of the Colorado Springs Police Department, infiltrated the Ku Klux Klan in the late 1970s.

As the harrowing scenes come to an end, Lee offers up an image of the American flag and turns it upside down and drains it of color, leaving it black and white. It’s a telling shot, one that serves as the backbone and theme throughout the movie: that America is and has always been a country that has failed to address its racist heritage, causing it to forever teeter back and forth between the black and white, the oppressed and the oppressor.

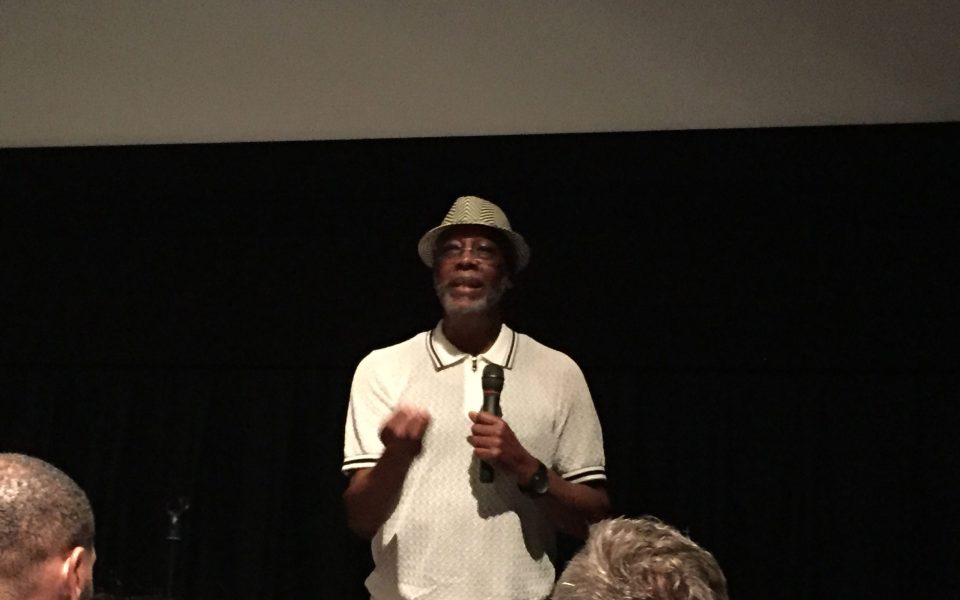

Larry Little, who attended a screening of the film at a/perture in Winston-Salem on Aug. 16, doubled down on the idea. Little grew up in Winston-Salem and helped found the city’s Black Panther Party in 1969, the first chapter in the South, before becoming a city alderman and, later, a professor of political science at Winston-Salem State University.

“I have a lot of emotions from watching the film,” said Little, during a dialogue at the end of the film. The event was part of a new series by a/perture and the New Winston Museum called the New Winston Dialogues that invites special guests like Little to lead conversations after select films.

The screening for BlacKkKlansman, which took place at a/perture, was sold out.

The film uses its bizarre premise of a black police officer infiltrating the KKK by pretending to be a white man on the phone, then using his white partner for in-person meetings to paint the film as a kind of comedy. And while the movie certainly has its moments for laughs, including when Stallworth unwittingly uses his real name to talk to the KKK for the first time, Lee makes sure to keep audiences woke by weaving real-life quotes by President Trump throughout.

KKK and white supremacists in the movie make references to “making America great again” and calling black people “murderers and rapists.” There’s even a scene towards the beginning of the film when Stallworth is told by his superior that David Duke, the Grand Wizard of the KKK at the time, is attempting to clean up his image to run for office to which Stallworth naively insists, “No one would elect someone like David Duke for president of the United States.”

Groans and laughs from the audience ensued.

Countering these lighter, yet all too familiar instances of racism are more serious accounts of the terror that the black community and other marginalized groups have had to face at the hands of white supremacy throughout America’s history.

In one of the tensest stretches of the film, Colorado College’s black student union invites a senior black activist, played by Harry Belafonte, to a meeting. There, Belafonte’s character, Jerome Turner, tells the true story of Jesse Washington, a black teenager who was lynched in Waco, Texas in 1916. The episode is one of the most gruesome accounts of lynching in history, with a white mob chaining Washington, cutting off his fingers and genitals, then burning him alive for hours. Photographers sold pictures of the event as postcards and children stopped on their lunch break to watch. As Turner recounts the horrors, members of the student union gasp and shake their heads.[pullquote]BlacKkKlansman will be screened at A/perture through Aug. 30. Tickets can be found at aperturecinema.com.[/pullquote]

During the film’s discussion after the screening, Little offered a similar story to the audience. He talked about the story of Clyde Brown, a black teenager who openly dated a white woman in Winston-Salem in the 1950s. After being spotted by the woman’s father, Brown was convicted of rape and found guilty by an all-white jury who sentenced him to death by gas chamber.

Little, who echoed Lee’s central argument from BlacKkKlansman, said that racism was and is alive and well in the city.

“In Winston-Salem, you don’t see the Klan but you see people in three-piece suits with the same racial biases,” Little said. “We have to come together to make the future that we deserve. We deserve better than the grand wizard. We deserve better than that.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply