The spare, undulating desert blues

emanated from the battery-powered speaker set up at the edge of the parking lot

outside Wise Man Brewing, a spidery web of electric guitars, bass and

percussion that was bracing and serene all at once, as yogis laid down their

mats to begin a session.

“This music is Tinariwen,” the

instructor said as she gestured across the parking lot towards the music venue,

where a cluster of Winston-Salem police officers kept a friendly vigil.

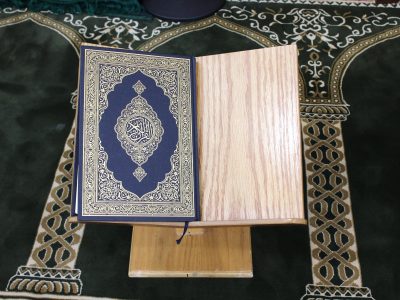

“They’re playing at the Ramkat tonight. Since they can be controversial, the

announcement that they were coming caused some backlash. People said they were

Taliban, but they’re the opposite of that. If you see a lot of police officers

in the areas, that’s why.”

When the Ramkat started publicizing the concert by the acclaimed nomad desert blues band of the Sahara on Facebook in July, a stream of hateful comments quickly ensued, apparently based on nothing more than that the band members were wearing turbans:

“Go home; maybe your country will

like your music.” “Gotta bring my AR, too….” “Take the fucking towels off your

goddamn heads.” “Shootout at midnight?” Taliban rock?” “Ain’t looking at

nothing Muslim. The wannabe religion that’s the plague of the world.” “Or bomb

us, your choice.”

The backlash made international

headlines.

But on Tuesday, a couple hours before the concert, Winston-Salem City Councilwoman Annette Scippio read a proclamation signed by Mayor Allen Joines declaring it Tinariwen Day in Winston-Salem. The Winston-Salem Symphony played a brief fanfare prelude to set the stage for the proclamation, while Imam Khalid Abdul Fattah Griggs and Wayne Martin, executive director of the North Carolina Arts Council, brought greetings.

At 6:08 p.m., shortly after the

ceremony ended, Ramkat partner Richard Emmett received a letter from Gov. Roy

Cooper. It was addressed to Tinariwen.

“North Carolina has a long history

of excellence in the arts, and we are proud of the diverse community of

musicians that have visited our state and called North Carolina home throughout

the years,” it read. “As you prepare for your performance at the Ramkat, I hope

that you feel at home here, and thank you for bringing your music and culture

to our state.”

In a political moment fraught with

fear, division, distrust and toxicity, at least for one moment and in one

particular place, love won.

While ICE is deported hard-working

community members like José Samuel Solis Lopez, a labor organizer at the Case

Farms plant in Morganton, President Trump came to North Carolina last week, and

whipped up fear, declaring, “North Carolina has released thousands of dangerous

criminal aliens into your communities, and you see it. The charges against

these free criminals include sexual assault, robbery, drug crime and homicide.

Murder!” In what has become a regular drumbeat of official hostility towards

Muslims, a Sikeston, Mo. public-safety officer resigned after stating on

Facebook: “I get to choose whom I dislike and it just so happens to be all

muslims [sic] and their beliefs.”

And on Monday, during a rally in New

Mexico, Trump casually demonstrated the contingent status of people of color in

the United States in 2019 when he pointed to CNN contributor Steve Cortes, and

asked, “Who do you love more, the country or Hispanics?”

Sometimes white supremacy is shut

down when community members show up and drive out extremists by crowding them and

yanking away their platform, and no one should doubt that those tactics are

effective. But it’s even better when a community comes together and makes a

statement of affirmative welcome and interfaith, multicultural solidarity that

speaks louder than hate.

“We don’t have to tolerate hate or

anything bad,” Scippio told me after the ceremony on Tuesday. “If people would

speak up and speak truth, and model behavior, we could defeat hate.”

Tinariwen proved during their concert

in Winston-Salem on Tuesday that the North Carolina Taliban picked the wrong

band to fuck with. Ultimately, the threats and bluster don’t affect them.

Ali Rogan, a producer with “PBS

NewsHour” who brought a crew to Winston-Salem to capture the scene, told me two

members of the band told her they weren’t even aware of the threats.

Among the three lead guitarists,

founder Ibrahim Ag Alhabib’s playing conveys the most weight and sadness — a

desert-blues meditation reverberating with modulating tone patterns.

This is a man who watched his father

get executed by a pro-government gunman in his native Mali at the age of 4,

whose band members participated in violent uprisings against the governments of

Mali and Nigeria in the 1990s, and whose band members escaped the persecution

of al-Qaida-inspired Islamists in 2013.

“I have no hate left for anyone, my soul is confused,” Alhabib sings on “Tenere Maloulat,” the opening track on Amadjar — the new album released on Sept. 6. “I believe in no one now. I’ve become the son of gazelles who grew up in the meanderings of the desert.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply