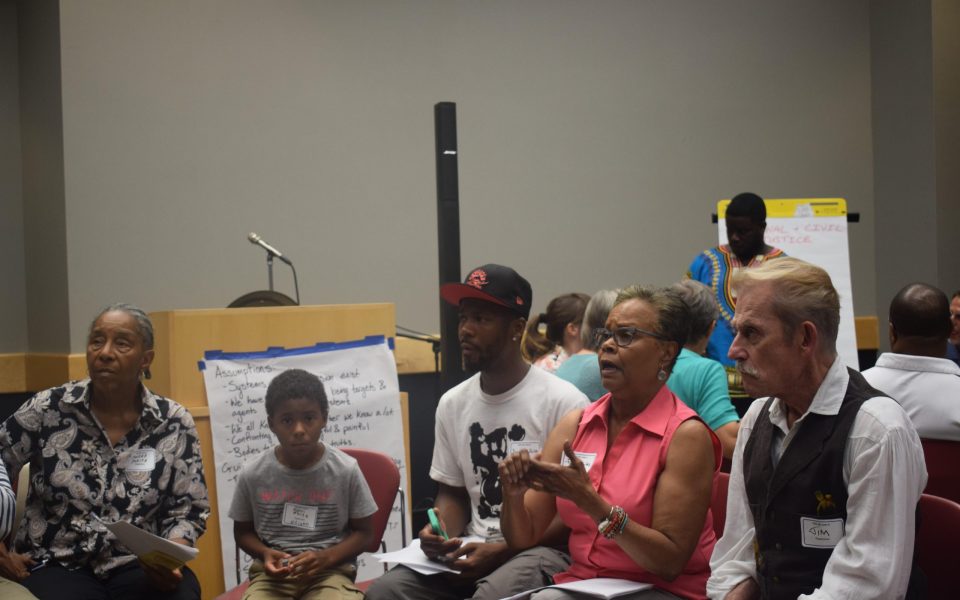

In the wake of Bernie Sanders’ concession to Hillary Clinton in the 2016 Democratic primary and disillusionment with national electoral activism, motivated Greensboro residents shifted focus to local politics and formed Democracy Greensboro. On Saturday afternoon, more than 120 community members convened for a summit, further deliberating the group’s platform.

Steering committee members facilitated working groups on four areas of concern: criminal and civil justice; economic justice; environmental justice; and social justice.

“I felt very strongly that we shouldn’t start with just selecting candidates,” said the Rev. Nelson Johnson, the executive director of the Beloved Community Center and pastor at Faith Community Church. “I thought we should start by figuring out how to unite our community. To me, the priority was developing a way to both build unity and clarity around what the community really wants; that is the basis on which a community can or cannot support a candidate.”

Throughout the summit, participants pushed for more intentional language in the platform. “Equity,” for instance, will replace “equality” because — as one attendee explained — although both are strategies for fairness, equity takes disparate vulnerabilities and needs into account when writing policy whereas equality prescribes one-size-fits-all solutions. Participants also agreed that demands should center the language of fundamental human rights like shelter, healthcare and education.

“When we’re talking about social justice, we’re talking about collective decisions, transparency and expansive participatory budgets,” activist April Parker said. “These things are at the root of collective democratic process.”

Parker, a librarian and organizer with Black Lives Matter Gate City, and other participants in the dialogue aim to reallocate Greensboro’s economic resources to sustain community-determined solutions.

“Right now, when you think about social justice in Greensboro, a lot of it looks like the nonprofit-industrial complex and not [funding] what communities are doing to survive,” she said.

Participants are also interested in addressing environmental racism; expanding public transportation; and resisting the disproportionate surveillance of communities of color.

No matter the issue or differences in priorities, community members agreed that the platform should offer policy suggestions to pressure elected officials to sign on to substantive action rather than simply issue blanket statements of support.

“You can say whatever you want to city council, but unless you have the power to compel them to act, you’re just saying it,” Johnson said. “The power is in a united people; power doesn’t need to beg.”

Volunteers will amass and present participants’ suggestions to a nine-person synthesizing committee charged with drafting the group’s new platform. While some advocated for brevity, others wanted to discard bullet point-style lists entirely. It is clear, however, that updates will be more specific and expansive in scope.

For example, some community participants pushed back on a handful of platform positions focused on housing conditions, arguing that criminalizing landlords would not serve marginalized communities as well as policies rooted in a conversation about gentrification; city council should prioritize community input when deciding the future of vacant buildings, some said. Previous calls for increased police accountability manifested in proposing an independent citizen oversight committee and launching independent investigations into past and future law enforcement abuses.

Democracy Greensboro will share the revised version with the public and encourage additional input on June 22 at 7 p.m. at a location to be determined.

The Rev. Johnson wants to offer training for people to go door to door in the run-up to the election. He believes young people will be decisive to Democracy Greensboro’s success.

“There has to be a process that earns the respect of young people and… orients both young and old people toward the things that are important [to them],” he said. “Electoral politics has been essentially used against young people, and until there is a sense that it can be used for their interests — and they can see that — I think the work is helping to create a mechanism that will work for them and helping them to see and join it.”

Though enthusiastic, Johnson and other leaders anticipate that broadening community input will introduce new difficulties.

“The work of democracy remains challenging, but it’s work that we can and must do together. The talking time continues, but the walking time must begin,” he said.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

The Establishment gather in their private homes secure in their phonyness.