by Liz Seymour

When I was in second grade my whole class made ashtrays for Christmas. Everybody’s parents smoked. Grown-ups would send their kids to the corner store to buy a pack of Winstons or Tareytons. The copies of Time and the Ladies’ Home Journal on the coffee table were filled with cheerful ads showing people making their daily lives better with cigarettes. And then 50 years ago the Surgeon General’s office issued its report on smoking and health and things began to shift. Cigarettes remained — and remain — legal, but the culture around smoking changed dramatically. Second-graders no longer gave their parents ashtrays for Christmas and doctors no longer smoked their way through medical consultations (yes, that used to happen too). Hundreds of thousands of people who would have died of tobacco-related diseases didn’t.

What will it take for us to apply the same national will to guns? Every time there’s another mass shooting we line up on either side and post and re-post angry things on social media and then stagnate into theoretical issues of constitutional rights and personal responsibility. And people go on dying.

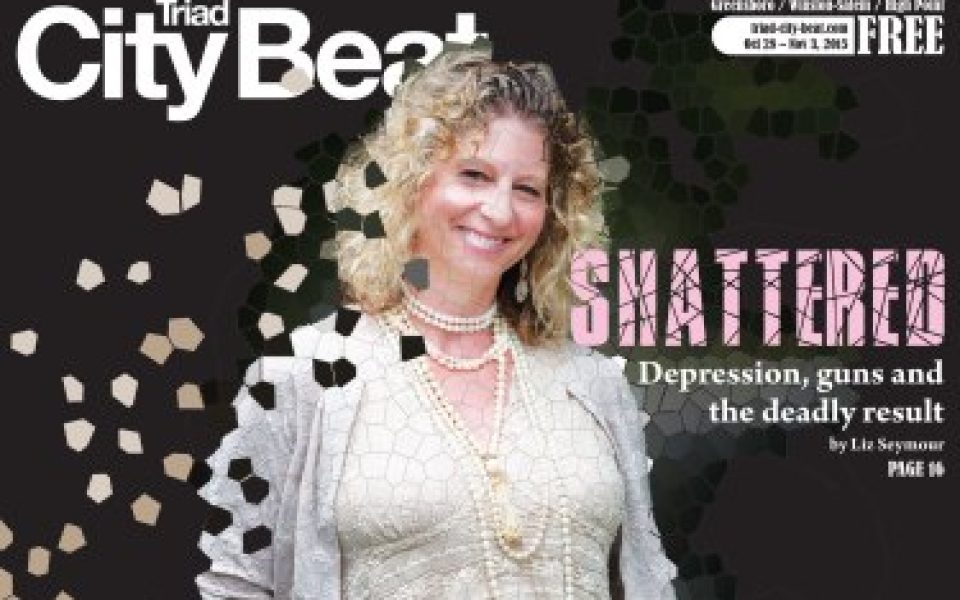

The cost of our American gun culture became painfully personal to me this past January when my beautiful, funny, smart sister Mary lost her way in the depths of a bipolar depression that her disease told her would never end. One chilly winter afternoon she lay down on her bed and shot herself in the head with a gun she had purchased earlier that day.

* * *

Something important to know about suicide by gun: At an 85 percent fatality rate it is by far the most effective method out there. The vast majority of those who survive a suicide attempt will never try it again, but once a gun enters the mix there are very few second chances.

Another thing to know about gun suicides: They are extremely common — more common than gun homicides, more common than accidental shootings and much, much more common than the terrible mass gun killings that dominate the headlines. Just look at the numbers: In 2013, according to the Centers for Disease Control, more than two-thirds of all gun deaths in the United States were suicides — 21,175 in all. That comes out to an average of 58 gun suicides a day. A day.

It has become commonplace within the medical community to define access to guns as a public health issue — so much so that the connection between guns and public health has stirred up a powerful backlash from the National Rifle Association.

Four years ago conservatives in Florida pre-emptively passed the so-called ”docs vs. Glocks” law that makes it illegal for doctors to ask their patients about gun ownership. Similarly, Dr. Vivek Murthy’s nomination for surgeon general was held up for almost 18 months largely by an NRA campaign that labeled him “President Obama’s radically anti-gun nominee.” His crime? Having tweeted, “Tired of politicians playing politics w/ guns, putting lives at risk b/c they’re scared of NRA. Guns are a healthcare issue.” Gun advocates went, well, ballistic. By the time he was finally confirmed in December of last year, Murthy had backed so far down as to promise that he would not use the surgeon general’s office as a “bully pulpit for gun control.” His position now is that we need more “common sense.”

* * *

It’s an odd part of the grief process, or the healing process, or whatever damn and unasked-for process I’m in the middle of right now, that every time I read a date a little clock in my head starts running backwards to where Mary was and what she was doing at that time. In May 2011, the month “docs vs. Glocks” was signed into law in Florida, Mary was starting a blog called Galloping Mind, subtitled “Musings on horses, humans, and life.” In the first entry she wrote about returning to horseback riding after a 25-year hiatus.

“I almost gave up,” she wrote, “but I sensed I would lose a lot more than a future with horses if I did. I’d be losing the self I was just beginning to construct — not the fearless girl who rode her pony bareback around fields at a gallop, but someone brave in a different way: a woman who was finding her own way, daring to be a beginner again, making peace with discomfort, and letting go of illusions.”

Mary returned to riding in her forties. Months before her 50th birthday she left a writing and editing job in Massachusetts, sold her house and moved to Greensboro where her two sisters lived. It was the end of 2008, which, as it turned out, was a terrible time to be making a change. Once she arrived in Greensboro, Mary couldn’t find another editing job; she ended up working in retail for $7.50 an hour and freelance writing on the side. One of her freelance articles was a wry, funny piece about her job search; that article led to a conversation with North Carolina Public Radio’s “The Story with Dick Gordon” about being a middle-aged, college-educated woman caught short in the recession. It made for great radio, but it was Mary’s own life and she was scared. One evening we sat on a bench in the Greensboro Arboretum while she cried and cried.

“I’m so tired of being plucky,” she said. Shortly after that she pluckily applied to graduate school.

In October 2012 when Vivek Murthy sent out his tweet about guns, Mary was a couple of months into a job she loved at the Mental Health Association in Greensboro. In May of that year she had graduated with a master’s degree in counseling from UNCG. Two months before that our other sister Abigail and I had forcibly taken Mary to the emergency room at Wesley Long Hospital.

“I tried to bolt,” Mary wrote later, “but my boyfriend pinned me in his arms and carried me, kicking and pummeling, to his car. I understood in a thunderburst of clarity that this was a cosmic test. The universal force that was giving me orders would show me how to surmount this newest obstacle. It would all become part of my enduring myth as the next Dalai Lama.”

Mary told us later that she had not taken her lithium for several months — whether she had stopped accidentally, stopped on purpose, or stopped accidentally-on-purpose even she didn’t know for sure. Once back on the lithium she returned quickly to center.

* * *

Read more:

It wasn’t the first time. Mary was diagnosed with bipolar disorder — the brain disease that used to be called manic-depression — in the summer of 1995 after a dramatic psychotic break. From that moment onward she worked vigilantly to keep herself on the middle path between the terrifyingly seductive highs and the soul-destroying lows that are the two poles of the disease, and for the most part she succeeded, becoming along the way a vocal advocate for greater public understanding of mental health.

She wrote about it — a piece she published in Newsweek in 2002 called “Call Me Crazy, But I Have To Be Myself” is required reading in some college classes — she lectured, she taught, she worked with individuals. She took up shardware, a mosaic technique that uses broken plates to make beautiful and eccentric works of art, and she taught it to other people with mental illness as a metaphor for finding the beauty in brokenness.

Still, Mary had a bipolar brain. At about this time last year, she started feeling depressed again. At first she attributed it to the change in the seasons — she hated winter’s long nights and cold days — and a change in jobs. She went to yoga class more often, rode her horse whenever she could, asked her doctor’s help in adjusting her medications, reached out to family and friends for support. Mary had been writing off and on about her own life; after she died we found fragments of a memoir.

“Depression is its own country,” she had written. “You don’t know exactly how or when you got there, but you know you want to get out. The country declares sovereignty and says you will live there until you die. Which may be sooner than you think.”

The particular depression Mary was writing about occurred in 1998, three years after her first psychotic break. It took two years for her to fully crawl her way out of that one.

“I grew used to days that were shaded from black to pale gray, grateful for any that were pearly,” she wrote. “I started therapy with a Buddhist-oriented practitioner and came to know the strands of anxiety, insecurity, fear, hopelessness and grief deeply woven into my psyche. I learned to sit with them and study them rather than push the feelings away.”

Eventually the pearly days began to outnumber the gray days, and then the sunny days outnumbered the pearly ones and Mary went on with her full, creative and satisfying life.

* * *

By October of last year it was clear that the depression had returned. Mary was educated enough in her own illness to recognize that this was the depression that inevitably, in the cycle of bipolar disorder, follows the mania — in this case just a couple of years late. By November she was describing a sense of despair and anxiety that rarely lifted; by December she had lost a noticeable amount of weight and was having trouble sleeping. To those of us who spent time with her every day, she seemed like someone disappearing under a sheet of ice, looking out at the world from a greater and greater distance. It was like her psychotic break but in reverse: a sharp parabola that felt like reality to her. But wasn’t.

“What’s so strange is that I am my own worst enemy,” she wrote near the end of December. “It’s my imaginings, my fears, that render me incapable. If I could only find a way to let go of all that fear. It’s irrational, really — I have enough money to get by for quite a while. It’s not about base survival — it’s about the mind playing tricks on itself, distorting reality.”

* * *

In 1996, in the wake of a mass shooting, Australia dramatically tightened its firearm-licensing requirements, prohibited several kinds of firearms outright and held a mandatory buyback of all the guns that had been made newly illegal. The firearm suicide rate subsequently fell by 57 percent. When Israel no longer allowed its soldiers to take guns home on the weekend, the overall suicide rate in the Israeli Defense Force dropped by 40 percent. Twenty years ago the state of Connecticut passed legislation that barred a person who had been a patient in a mental health facility within the last six months from purchasing a gun, and started mandating an eight-hour safety training course for anyone who wanted a gun permit. The firearm suicide rate fell by 15.4 percent. To receive a gun permit in Massachusetts, where Mary was living when she experienced her first big depression, you must fill out and mail in a hard-copy application, be fingerprinted and photographed, pay $100 and take a certified gun safety course. Massachusetts has one of the lowest overall suicide rates in the United States, fewer than ten for every 100,000 people.

* * *

In early January, Mary spent a couple of days in a mental health facility in Winston-Salem, hoping that a new regimen of medications might begin to reverse the despair that had overtaken her days and her nights. She came home from the center on a Thursday evening feeling little better. On the Saturday after she got out, she sat down in her sunny workroom overlooking her sloping backyard and wrote: “Today I signed up for a gun permit. Apparently it takes 5-7 days for the permit to come through. The thought of buying a gun and shooting myself terrifies me, but so does the idea of living any longer. Maybe my meds will kick in during the next few days and none of this will happen.”

Mary applied online and paid the $5 application fee. On Tuesday around noon — fewer than two business days after her application was submitted — she received an email from the Guilford County Sheriff’s Office letting her know that she had been approved and could pick her permit up from their office.

Perhaps given another couple of days the meds would have kicked in as she hoped, perhaps a good night’s sleep or a warm day or a decent meal would have been enough to alter her state of mind, but now we’ll never know. Five days after applying for a gun permit, Mary was dead.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

This is heartbreaking. A close friend did the same thing, purchase a gun to end her own misery, but unfortunately she survived the attempt. I say unfortunately because of course, she will never be a whole person again. I wonder how many more, attempt suicide and do not succeed?

I’m so sorry for your pain. Mary was a lovely person and you both are wonderful writers.

Oh come on…. so now a person’s decision to end their life is the fault of the gun? This sort of nonsense needs to stop. Personal responsibility must return to our society.

My brother in law committed suicide about 10 years ago. He stuck a hose into the exhaust pipe of his car, routed it inside, rolled up the windows, started the car and did the deed. What does this say about automobile culture in this Nation? With such easy access to automobiles no wonder we have so many suicides, right?

We never once thought about blaming the automobile for my brother in law’s suicide. It was no more culpable than a gun in such situations.

At least there are some wiser heads still around – how the automobile became a suicide machine:

http://paleofuture.gizmodo.com/how-the-automobile-became-a-suicide-machine-512698751

The author’s last paragraph sums it up perfectly: “Suicide existed long before the automobile arrived. But every piece of technology is simply a tool that has no opinion of its own. How we choose to use them is obviously up to us.”

I have lost two very good friends to suicide…. one by gun and one by falling on a knife. Both were Bi-polar. I blame neither the gun or the knife; what I do blame is the poor state of the mental health medical attention that is afforded the one’s who need help. The war on drugs is a failure; why not direct that money to make it very easy for the mentally ill to get the treatment they so sorely need?

Mary was a wonderful and beautiful person, and it is heartbreaking to know how close she may have been to coming out of this. I agree. The process for obtaining a gun and permit is far too easy. This is a story to be shared to advocates, policy-makers, and everyone in between. Her story and presence will live forever in my heart.

Thank you for courageously sharing Mary’s story and for making these devastating connections with gun availability. The clarity you bring and connections you shed light on through this story are so important. What a tremendous tribute to your sister and contribution to our community.

Thanks for sharing this Liz. As someone who has lived with a loved one with mental illness for over 30 years, much of your family’s story resonates with me. The peaks and valleys, the hope and despair, the irrational fears. Thanks again.

Steve McLeoad it’s the fact that she bought a gun and killed herself the same day. If we had a national background check and it took a week, maybe she would have gotten back on meds or changed her mind. Nobody wants to take your rights away just some common sense laws.

Or if, as some insist, we pursued the mental health angle perhaps the fact she was on anti-depressants would have triggered a flag in the background check process.

No matter why or how someone takes their own life, it is a horrible, tortuous event. Leading up to it, the act, and the fallout and damage one to the victim’s loved ones left behind must be most devastating.

My heart and love goes out to all who are pulled into this frightening abyss.

Mary, our son was almost 30 years old when he was playing Russian Roulette and killed himself. He had always been impulsive and made bad decisions. He had played the game before and said he was bullet proof. Sadly, the gun he used was one my husband had removed from a friend’s home because the friend was suicidal. Although it was hidden well, while Charlie was searching for something else, he found it and showing off to a friend, he killed himself. He also suffered from BiPolar.

I knew Mary well and from a different perspective. I watched my beloved friend, supervisee, and colleague suffer in physical torment from a mental illness with no relief. Regardless of the means to which she took to end her suffering, it leaves behind a ripple effect that no one can stop. I’m a mental health professional that has spent over 4 years in an ER hospitalizing people just like Mary. I’ve worked in prisons, and in inpatient mental health facilities. I was always diligent and checked in with her, asked her how she was doing as I did every Monday. The Monday before her death, she looked me straight in the eyes and lied to me. But we both knew she was lying. She had said to me the same thing she said in her memoir, “maybe the meds just need a few more days.” I in no way blame myself or anyone else. I am an avid gun owner, I used to be a police officer. However, I never knew it was ever possible to apply online for a gun permit till her sister Abigail told me. I was FLOORED! None of us can say for sure that she would still be here today had that gun permit not gone through. But I can say, that if the mental health arena had done their job, chances are, Mary would have never received that gun permit. People can’t be checked against involuntary commitment orders (IVC) when they are properly filed with the Magistrates office. Often times they are destroyed and are ever submitted to the proper authorities. Why? Because providers don’t want to “ruin” patients lives!!!!! This is the real deal folks. Often times people are told the are on an IVC hold while inpatient, when often times those papers have been destroyed once the person calms down and willing to go. The patient and their families just aren’t often told. So unless your family member is actually transported by law enforcement, you can pretty much count on the papers were destroyed and the IVC process was never completed. But lets say it had been, Mary would have had several more days to let the meds work. Knowing Mary as I did, she would have been too chicken to purchase a gun illegally. The permit coming through was as if the “powers that be” told her, yup, this is your plan and this is your destiny.

Mary, I will forever be grateful to the love and compassion you showed Maddie by sharing yourself and Mystic with us. I love you and miss you terribly!

Abigail where are you

If you want to die, you will find a way. It does not matter how but it does matter that we should be able to choose and do so with dignity, mental illness or not. It is my right. I choose to live now but who am I to judge?

The mind and heart behind the hand is the responsible and forgivable force behind the action. Time to stop blaming utensils. Come on, Drano is a solution, do we ban it?

I don’t think the author is blaming the gun. She feels like it shouldn’t be so easy to get one. Especially when you have a history of depression. Research studies have shown that a suicidal person that has to wait a significant amount of time to get a gun will end up not attempting. My personal struggles with depression bares that out. If I had access to a gun I would most likely be dead. There’s a reason why I don’t keep one in my home. Obviously people can still kill themselves other ways if they are determined. But for most people that wait can move them to get help. So the gun isn’t to blame. The easy access to firearms just makes it significantly easier. Especially for people acting impulsively.

“If you want to die, you will find a way.” I used to think this too, but it is simply not true. Access to highly fatal means is a major risk for suicide. The author addresses this when she informs us that the vast majority of survivors of attempted suicide do not repeat the attempt. People headed toward suicide from bridges (another highly fatal means) who are interrupted and directed toward a hotline or other support are unlikely ever to kill themselves.

She could do a better job of making this point. For example, she tells is that after Australia enscted gun restrictions, firearms suicides plummeted. What she doesn’t day, but is the crucial point, is that TOTAL suicides plummeted. People denied guns could have taken pills instead, or hanged themselves, etc., but that’s not actually how suicide works. The means available make a huge difference in whether someone dies or finds a way out of their quagmire.

The callous remarks here about “personal responsibility” make my blood run cold. Of course no one but the individual is ultimately responsible in suicide. But who would knowingly put a gun in the hands of someone suffering a bout of depression? And yet that is what our current system does.

What you do, when someone you care about is suicidal, is keep them away from the means to kill themselves, and get them help. You don’t shrug your shoulders and say “Oh well, it’s on them.” That would be a fatalism that is the same lie depression tells its sufferers.

Anyone determined to end their life will find a way to do it. On of our friends shot himself..another hung himself and my step-sister stepped into a tub filled with warm water and cut her wrists. All had depression problems..but my step-sister had been mentally for 30 years. She would still be alive today if it were not for Carter and Rivera..when they convinced the public that noone needed to be in a facility unless they killed someone. We could never have her committed longer than 120 days…she would get out..stop taking her meds and end up God only knew where..doing what..with who knows who..our stories are endless. There really are people that we need to take care of..if we want them to live. It wasn’t the fault of the warm water and the razor blades..it was the extreme political correctness that has gripped our country for far too long.

We all mourn when friends leave us, and part of that mourning is for our own comfort — for death is what we’re fearing; when others die, we are reminded of our own mortality. Nonetheless, it’s the person’s own decision what to do with their life.

I find some of the comments quite callous. Nearly 90% of people who try to commit suicide and fail to complete it do NOT go on to try it again. Therefore, the means chosen is critical. The fatality rate for gun suicide is 85-90%. The time from thought to action is usually quite short-it can be even seconds if there is a gun accessible. Using a gun does not allow time for second thoughts or someone else to intervene. I recall vividly the statement of a young man who jumped from a bridge and survived. He said, “Half-way down I realized I didn’t want to die.” If he had chosen a gun, there is nearly a 90% chance he would not have survived. And another statement some commenters should remember: Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem.

Thank you. Well said. I don’t think most people realize how impulsive of a decision it can be. Most people at least have some ambivalence about it. Staying alive a little longer can make a difference.

I agree that quick access to guns should be prohibited. I believe doing so would not stop, but would reduce suicides and hate related murders. It would be difficult if not impossible to calculate how many deaths such laws would prevent. No one knows exactly how many thefts are prevented by watchmen, but watchmen do prevent thefts.

I disagree with the statement “Suicide is a permanent solution to a temporary problem.” That may be true in some cases, but terminal illness is responsible for many suicides and it is not temporary.

I own a few guns, but am NOT a gun rights activists. I believe many gun rights activists fear any move to keep guns out of the hands of people with mental illnesses is because they have one.

I also suspect that it might be advantageous to have a 24 hour waiting period before e-mails are sent. 🙂