What’s an editor to do when the biggest scandal of the young century drops on his desk?

This one had it all: Prohibition-era booze, a fancy neighborhood, crooked cops, hookers, a cover-up and a list of willing participants that reached into the highest echelons of Winston-Salem society. Allegedly.

It was the biggest story the city had seen since Santford Martin took over the editor’s desk of the Winston-Salem Journal, the city’s morning paper, in 1912 — just two years after taking a job as a reporter there.

And it came to him through reporting both solid and kind of sketchy, teasing out a short exchange that occurred during a trial about a completely separate matter. Martin honed in on it, began gathering facts and employed a little bit of journalistic gamesmanship to bring this one to light.

Momentum gathered on the front pages of the morning Journal for more than a week, when the story inexplicably vanished from the newspaper of record.

It’s likely that Martin didn’t know exactly what kind of tiger he had by the tail on the night of Saturday, Sept. 19, 1925, when he laid in copy for the next day’s paper with a juicy detail from the trial of Mrs. Grace Renner, who had been arrested for stealing a hat.

DAY 1

Sunday, Sept. 20, 1925

Woman’s Hint of Night Ride With Cops Stirs Court

Policemen’s Names are Linked With Ardmore ‘Parties’

Mayor and Chief in Secret Parley

Winston-Salem’s 12-Day Scandal began with a Sunday morning off-lead news piece, running on the left side of the broadsheet above the fold.

Following the three-line headline, just two columns across, were a series of subheaders in the newspaper style of the day.

It certainly sounds pretty juicy.

The story recounts a trial the day before in municipal court involving Mrs. Grace Renner, who had been convicted for stealing a hat, fined $25 and given a six-month suspended sentence.

But the nut paragraph concerned testimony from Mrs. Charles Johnson, Renner’s sister. While she was on the stand, Martin reported:

Judge Watson stated that he had received a number of complaints charging that dances and liquor parties were being held in the home of Mrs. Johnson; and that many people, “both married and single,” were frequently seen at the place.

Now here’s where a little context comes into play. In 1925, the United States was six years into the grand experiment known as Prohibition, making it illegal to sell, manufacture or transport “intoxicating liquors” anywhere in the country.

We all know how that played out. But it would be eight more years before Prohibition was repealed. And though cops all over the nation turned a blind eye to the black-market liquor business, the idea of it happening in Ardmore was just too much for a guy like Santford Martin to take.

It’s important to note that Martin was what could be described as an “ardent prohibitionist.” And that North Carolina had been dry since 1909, 10 years before the rest of the country.

By 1925, Martin had already graduated with a law degree from Wake Forest University, worked as private secretary to Gov. Thomas W. Bickett, been named president of the NC Press Association, served on the state fisheries commission and sold war bonds during the Great War. And by that year, North Carolina had perhaps more illegal stills than any other state in the union.

It must have galled a man like Martin, whose editorship at the Journal marked a period of repressive politics — including segregation, which he hoped “negroes” would settle into “voluntarily.”

His feelings on alcohol are best illustrated by an anecdote about Martin and Marshall Kurfees, who served as mayor of Winston-Salem from 1949 to 1961 and was solidly on the “wet” side of the issue.

As the story goes, years before he became mayor Kurfees told Martin that he could throw three rocks from the Journal’s offices and with each hit a place where he could buy a drink.

Martin then had Kurfees subpoenaed; he found himself before a judge that very day with orders to disclose the speakeasies.

Kurfees unflappingly named the Robert E. Lee Hotel, the Twin City Club and the bus station, and then named three prominent political and business figures who routinely drank there.

As the story goes, Kurfees left the name of the reigning mayor off of the list. None of the names made it into Martin’s story in the Journal the next day.

Now, about those “parties”….

Suffice it to say that an editor like Santford Martin could never bring himself to put the word “whorehouse” in his newspaper.

The Sunday newspaper piece had Mrs. Charles Johnson — as she would be referred to in the Journal every single time throughout the scandal; we never learn her first name — in a car late Friday night with two Winston-Salem police officers. Riding around in cars had connotations of its own in those days.

And according to the piece, it was municipal court Judge TW Watson who addressed the parties after they were brought up during cross-examination. Martin quoted him as saying:

“It is a question as to whether or not it is best to aggregate these people and have them where the police can watch them all the time, or to have them in the best hotels and the best residential sections of the city.”

Martin must have learned about an emergency meeting between Mayor Thomas Barber and police Chief James Thomas, because he began questioning them about it. The mayor had no comment. Chief Thomas dropped a great quote:

“What investigation? I haven’t heard anything about any investigation. You must have heard some rumor that hasn’t reached me.”

The story could have died there, but Martin, empowered by the Sunday A-1 piece, began doing some digging. Things started to move quickly after Martin spent the rest of Sunday pestering the mayor and police chief.

One final piece of context: Winston-Salem, like most US cities, was a two-newspaper town in 1925. The Journal, which had not yet merged with the Sentinel, came out in the morning. The Sentinel was an evening paper. And they wouldn’t bite on the story for days.

DAY 2

Monday, Sept. 21, 1925

Woman’s Story of Night Ride Brings Suspension of Cop

Monday morning’s Journal ran the story as the lead in the upper-right corner, a follow-up to the previous day’s big scoop. Now Martin had a name: Sgt. WM Cofer, who had been suspended, and another, “plain-clothes officer” Gregory, who had not. Martin figured both had been along on the night ride with Mrs. Charles Johnson.

Both the mayor and the chief still were not talking, so Martin mined the testimony from the previous week’s trial, naming Miss Evona Allred as the one who brought initial charges against Mrs. Renner for stealing the hat. And he wraps the piece with a bit of editorializing — not necessarily inappropriate considering the journalistic standards of the day.

While the case is considered by some as small within itself, it is believed to have brought to a head an intolerable situation in the city which must be cleaned up. On the particular street where these ‘going–ons’ were testified in court to have taken place, many people are said to have declined to rent apartments because of the moral situation.

And because of his dearth of material, Martin penned a gut-wrenching, flag-waving A-1 editorial under the headline, “Turn on the Light.” Among the highlights:

Instead of attempting to shield officers, if they are guilty, the responsible executive

authorities of Winston–Salem should be anxious to turn on all the light through the channel of publicity….This is not Russia under the Czar or Germany under the Kaiser. Under our system of government, the people have a right to the fullest information possible concerning all public officials….

Secret government is the vilest fruit of autocracy and is opposed to the very genius of American institutions.

Santford Martin could really blow it up once he got going.

DAY 3

Tuesday, Sept. 22, 1925

Ardmore Scandal Arouses Alderman to Oust Cofer;

Police Inquiry Demanded

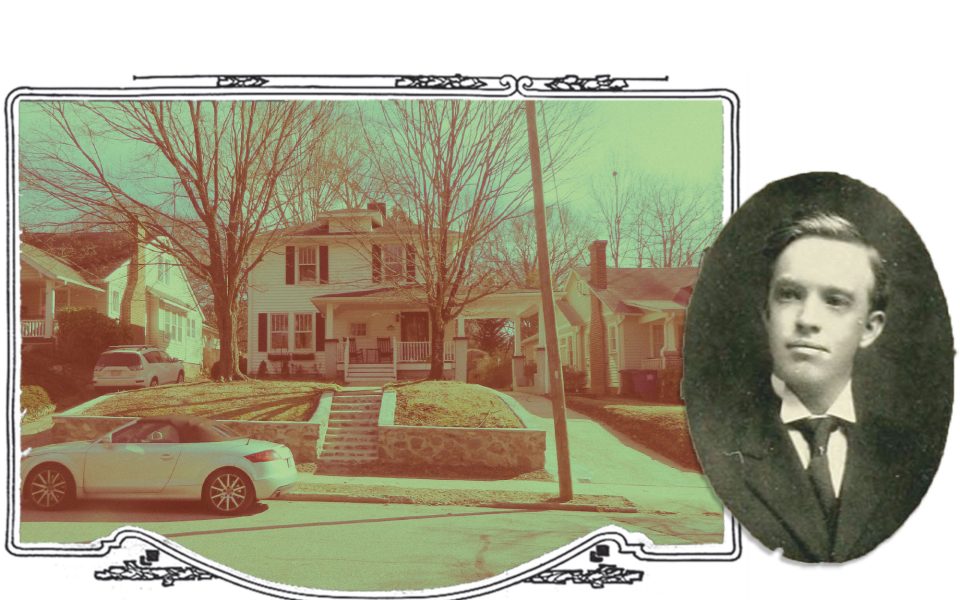

Tuesday’s coverage ran across four columns on the upper-right side, an update on the Cofer situation — he was fired — and news of a series of affidavits sworn by neighbors of Mrs. Charles W. Johnson, who by now had acquired a middle initial and also an address: 1824 Elizabeth Ave. It was also reported that Mrs. Johnson and her sister had left town, but had been seen on city streets the day before.

Three headshots ran above the fold, one of Chief Thomas — “has answered none of the charges that officers of his department frequented a house of ill-fame on fashionable Elizabeth Avenue” — one of city solicitor Phin. E. Horton, who had spun the affidavits and court testimony into a demand for a pubic investigation; and one of Judge Watson, who first heard the case.

Of prurient interest was the complete text of the affidavits, which ran on A-1 under the italicized headline: “Ardmore Citizens Make Affidavits, Complaining of Immoral

Rendezvous.”

“Mesdames RA Spainhour, Laura A. Cox, SE Sprinkle and Messrs. RA Spainhour and SE Sprinkle” — women were referred to by their husbands’ names in the paper back then — called the Johnson home “a blot on this community,” a place of “drunken laughter and singing at all hours of the night,” with “partially clad men in the home,” some of them police officers.

Martin wrote:

They declared unanimously in the presence of their curly–headed children, most of whom were between four and six years of age, that they had reached the limit of their endurance in trying to rear their families under such unspeakable conditions….

But he saved some pomp for the lede of the main piece, where he dubbed the 12-Day Scandal “the greatest city and police scandal that ever has broken in Winston-Salem’s history.”

By the third day, city aldermen had convened an emergency meeting, though none of them nor the mayor would tell Martin what transpired.

Bereft of official statements, Martin took to the streets of Ardmore and asked the people of Elizabeth Street about their neighbor. In this reporting, Martin begins to insinuate the people who frequented the house at No. 1824.

A man weighing 200 pounds and of jovial face.

[A] slender man in khaki who rode on a motorcycle.

[A]t least three officers and half a dozen prominent citizens of the city had been frequenting the Johnson home for a long time.

Some of the women in the neighborhood appealed directly to former

Mayor James G. Hanes while he was in office — but before they reached home Mrs. Johnson and her sister, Mrs. Renner, it was stated, came out on the porch and laughed at them.

One neighbor quotes Mrs. Renner as saying, “I guess the mayor told those people who have been attacking me where to get off.”

And with that, the city was on notice. This could get very bad.

DAY 4

Wednesday, Sept. 23, 1925

Barber Leads Probe to Clean Up Police System;

Thomas at Last Speaks, Defends SilenceCitizens Aroused

By Wednesday, readers had begun to latch onto the story as emblematic of life in the city under Prohibition. A political cartoon submitted by RC Flynt of 1902 Beach St. ran prominently on A-1 of the morning Journal.

It depicted the Journal itself as a glowing light in the upper-right corner of the frame, not unlike a sun, with a policeman’s cap lending shade to a whiskey bottle marked “CRIME.”

Martin also published letters from former city alderman and state representative OE Hamilton and Geo. D. Clodfelter in support of the paper’s reporting on the matter.

By now, the police department was in full-on manhunt mode for the two women, who were last seen in Pittsburgh, and Martin took glee in the chaos his reporting had wrought, relaying “varying reports of thirty to forty citizens occupying the anxious-seat of fear that their names will be revealed in the investigation.”

He wrote of “an unprecedented sensation” among citizens, and salted innuendo throughout his writing:

People were aroused, and the city was filled with a thousand rumors of what was going to be done. Winston–Salem’s scandal was discussed on the street, in stores, in busses, on street cars and everywhere men and women gathered.

The B story gave an interview to Cofer, the dismissed cop, who called himself a “goat.”

His frequent visits to the Johnson home, he said, happened because of a longstanding friendship with Mr. Charles W. Johnson, “a fellow member of a railroad fraternal order.”

He went there in an official capacity to investigate rumors of dances, but said he found nothing of an illegal nature, and that he had never received a complaint about the house until he saw the affidavits of that week.

He admitted, however, to the night ride with Mrs. Charles W. Johnson.

Martin also quoted the officer’s wife, identified only as “Mrs. Cofer”:

Holding a five months old baby in her lap, she told a story of his fidelity as a husband and father, declaring that during their fifteen years of married life practically all his time had been spent at home, pointing out a large rocking chair on the porch, broken by the weight of the deposed sergeant, where he had passed his hours while off duty.

Cofer’s son, Martin reported, had only learned of the scandal while selling the Journal on the street.

The boy had sold over 50 papers before a neighbor boy called his attention to the story of his father’s disgrace, and then dropped the papers and returned to his horse in tears.

DAY 5

Thursday, Sept. 24, 1925

Rumors of Suspension of Eight Police Officers Stir City Police Department Scandal

By Thursday, information had slowed to a trickle. Martin had learned that his story could implicate some of the city’s most powerful people. None of the city officials would comment on the record, and alderman Norman Stockton, an upscale haberdasher whose store survived in the city until 2010, called Martin personally, saying, “The Journal is the last paper I shall ever advertise in. It shall never have a line of advertising from me so long as Santford Martin is its editor.”

Martin boxed the quote and ran it on the front page.

The city had been squirming under the weight of Martin’s reporting, which had been discussed “on the street corners, in drug stores and hotels yesterday and last night by hundreds of men, and in many instances women.”

It now looked like eight cops would be suspended, though no names were mentioned. Martin accused the city of a “clam-like attitude” after officials heard testimony from neighbors and police.

The sole story ran maybe 12 inches along the right-hand side of Page 1, with headshots of the mayor, mayor pro tem and officer an Teague, the man who arrested Mrs. Grace Renner, filling out the front page.

DAY 6

Friday, Sept. 25, 1925

Attempts to Quash Police Inquiry Are Laid to Higher-Ups

The lede wrote itself: “High officials of the police department are doing all in their power to hush up the investigation and exonerate the officers under fire, it was learned yesterday from a reliable source.”

Martin was in a jam. No one was talking to him, but the scandal had captivated his readers, whose appetite for the story seemed insatiable. And he knew by their silence he had the bad guys running scared.

But all he could muster for the front page was speculation on the gravity of the scandal and how far it went, while the mayor and aldermen conducted their investigation that Martin deemed a farce.

As soon as civilian witnesses are heard, it has been declared, the forces of the department are marshaled to develop evidence to kill the testimony of residents and other witnesses

that police officials frequented a house of ill–fame on Elizabeth Avenue….This development, it is believed, throws a light on the investigation hitherto little suspected of existing.

He also got a juicy secondhand quote from a Capt. Herbert C. Whiteheart of the Winston-Salem Police Department, who was reported as saying, “Residents of Ardmore are a lot of ignorant country trash whose homes are on a piece of white paper, and all are liars!”

“Captain Whiteheart branded the story as false,” Martin reported, “[and] declared that he was willing to meet the author of the story anywhere and face him in it.”

But as the newspaper hit the streets and began circulating, Martin would dig something up for the Saturday edition.

DAY 7

Saturday, Sept. 26, 1925

Ex-Cop Charges Police With Protecting Whiskey Storage; Says Probers Hushed Him

Rum Cache in Elite Suburb Ignored, He Declares

It was true: The city investigation had been a circus designed to hide information rather than reveal it, according to an anonymous former cop whom Martin had convinced to talk.

In the course of the investigation this officer had stated that he had arrested a citizen in the Ardmore neighborhood, and in the course of investigating that crime he had come upon a store of liquor, 15 gallons worth, in an “elite suburb of the city.”

The officer said that when he reported this information to his desk sergeant, he had been told, “It is best to let matters of that kind drop.”

Martin’s lede hit hard: “The police department refused to take action to capture a liquor supply of 15 gallons in an elite suburb of the city.”

Quotes from JH Lancaster, from RFD No. 3, provided more salacity to the tale: an episode in front of the house, where Lancaster and his wife sat parked in a car and witnessed two police officers engaging with a “poodle-dog” that apparently lived in the house. As the poodle returned to the porch of 1824 Elizabeth Ave., two women blew kisses to the officers.

Since the story broke, nine “women of bad character” had been arrested, two from the Robert E. Lee Hotel.

The mayor had yet to make a statement to the Journal, but the stakes were getting higher. Martin’s turncoat cop had begun naming names.

The former policeman who last night charged the police with protecting liquor dives, called names freely, involving some of the highest officials in the department, but due to the fact that he was not willing to have his name printed now, the specific charges against individuals of the department temporarily are withheld.

Martin also remarked that a grand jury was set to convene on Oct. 5, less than two weeks away, and floated the notion that some of the cops charged with frequenting the house might be indicted.

He also published a cartoon submitted by SH Adams, of 54 West End Blvd., a former cartoonist on the staff of the Duke University magazine. It depicted a lighthouse casting twin beacons marked “publicity” and “investigations,” with a ship in the distance whose caption has been lost to the vagaries of microfilm. And there was a letter from James Atkins, president of the North Carolina Press Association, commending the work.

DAY 8

Sunday, Sept. 27, 1925

Ousted Sleuths Complain of Protection for Higher–Ups;

2 Detectives Fired Saturday

Martin’s Sunday edition led off with a cartoon from JC Teague, “who resides near this city.” It shows a uniformed cop walking a tightrope clearly labeled “line of duty,” with a scrolled up newspaper on one end marked “public press” and another guy dressed like a fisherman or something similar. Both of them have spears. The cop’s shoes are muddy, and the mud pit below the tightrope reads, “crime.” The message is broad but effective.

But the big development came from the city: Two cops, Ronda Gregory and Benjamin Phelps who both worked under the discharged Sgt. Cofer, had tendered resignations. The cops told Martin that the committee had refused their resignations and had instead fired them outright.

But the piece has none of the indignation and innuendo that marked the ones leading up to it, instead leaning on statements from the officers. This would prove to be Martin’s undoing — human sources give great color and context to a story, but they are fallible.

The two cops got the front-page treatment as heroes. But a counterstrategy seemed to be at work behind the scenes, as evidenced by the next round of coverage.

DAY 9

Monday, Sept. 28, 1925

Ministers Throughout City Demand ‘Light’ on Scandal;

Thorough ‘Clean-Up’ UrgedPulpit Leads in War Against Vice

By Monday, Martin’s zeal must have cooled somewhat. So he relied for Monday’s paper the content of sermons that had been preached in the city’s churches the previous day, in some cases cribbing the entire text.

In Sunday schools the Men’s Bible classes especially adopted resolutions endorsing the action of those who took the first step toward cleaning up the city…. Many expressed themselves as being of the opinion that the investigation should continue until all immorality had been wiped from the city’s fair name.

But there were no photos, no cartoon and no more speculation about “higher-ups” in the city and police department.

It looked like Martin was pulling back on the story. And forces were at work to silence Martin’s crusade.

DAY 10

Tuesday, Sept. 29, 1925

There was no mention of the Ardmore Scandal in Tuesday’s morning Journal. The main story was on the Cole murder trial taking place in Rockingham County.

Meanwhile, Martin’s police informants were being questioned themselves in downtown Winston-Salem, in a special hearing convened to shed light on the scandal.

DAY 11

Wednesday, Sept. 30, 1925

AW Ogilbie Held on Run Charges as Result of Inquiry

Keeping Liquor in Elite Area Alleged

The day’s Journal was marked by a rare headline typo — the man’s name was Ogilvie, it eventually was revealed. But that was a minor detail.

Ogilvie worked at the Westover Golf Club, arrested on testimony from Officer PC Flynt, who turned out to be Martin’s anonymous police source.

Flynt told police the day before that Ogilvie was the man he had arrested for drunkenness and who had shown him the 15 gallons of illegal liquor, stored in jars and kegs in the locker room at the Westover Golf Club, a new nine-hole course with homes built on the periphery just outside of Ardmore. Ogilvie’s trial was set for that very morning.

Flynt had spent the previous day in police court preparing for Wednesday’s hearing on the matter; Martin caught up with him later that evening.

At his home last night Flynt declared he told the committee a straightforward story and he would be at the trial in the morning.

There was also some news of Mrs. Charles W. Johnson, who had been seen in Lynchburg, “but this report could not be confirmed up to a late hour last night.”

DAY 12

Thursday, Oct. 1, 1925

Ogilvie Acquitted as Flynt Fails to Hold Up Liquor Charge

Evidence wouldn’t Convict Cur, Says Watson

Thursday’s headline said it all: Ogilvie’s trial resulted in an acquittal before the day was done. Judge Watson provided a money quote from the bench:

“I have heard enough,” he declared. “This case has grown nauseating to me, as it must have to others in the room. I would not convict a mangy, yellow cur dog with a black tongue on the evidence of that man.”

“I am gong to dismiss the case and recommend that PC Flynt go off and form a co–partnership with a polecat. I warn him to play straight or the skunk will desert him. I regret to say that men have probably been wrongly convicted in the past on the evidence of this man, for having lied today, the chances are that he has lied before.”

The main story ran in the upper-left corner of A-1, just about 14 inches, most of it summarizing the day’s testimony in which the charges made by Martin’s main source, Flynt, were dismantled one by one.

Ogilvie denied that Flynt ever came to the club that Sunday.

The mayor and mayor pro tem testified that they had not dismissed Flynt from the force.

Flynt’s sergeant, whom Flynt had said told him to let the matter drop, testified that the conversation had never happened.

Two members of the Westover Golf Club, a man named Ed Conrad and a Dr. Mason, testified that Flynt had not seen anything unusual that evening at Westover.

And the final nail in the witness’ coffin came from a Forsyth County sheriff’s deputy who also had the last name of Conrad.

The captain testified that he had arrested Flynt for immoral conduct in August out in the county, after catching him parked by the side of the road with a woman who was not his wife.

Under cross-examination by Ogilvie’s attorney JH Clements, Flynt himself eventually denied knowing anything.

Martin ran the entire transcript of the hearing, possibly to illustrate just how ridiculous the matter was. In one exchange, Clement asks Flynt about the report he had made before the police committee the previous day.

Q: What did you know that you didn’t tell them?

A: I knowed things I don’t care to tell now.

Q: What are they?

A: Don’t care to tell them.

Q: I want to hear them.

A: I can’t be made to tell them.

Q: Why can’t you be made?

A: Because I don’t know them.

Q: So you don’t know anything?

A: Yes sir.

Clements also pursued Flynt’s statements to the Journal, which contradicted the testimony he was giving that day.

Q: Have they printed anything at all that is true that you said?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What is it?

A: I can’t recall.

The transcript was the last piece printed in the morning Journal about the 12-Day Scandal.

POSTMORTEM

So what happened?

It’s possible that Martin allowed his zeal for Prohibition to cloud his judgment on this story, which threatened to tear away the veil of false sobriety the city had clung to for decades.

It’s possible that he cooked the quotes from the cops, that he coached his interview subjects to tell him what he wanted to hear. It’s certain that he printed secondhand and hearsay information, stacking the deck to dispose readers towards his position.

But it certainly looks like Martin was onto something, even if the only evidence was that he was printing things that many powerful people would have preferred he left alone.

And that’s what good journalism is all about.

Telling too is the way the evening paper, the Sentinel, treated the story.

In the days of Prohibition, a wet-dry divide existed in most cities, and while Martin’s paper was avowedly dry, the Sentinel was decidedly less so.

The first mention of the 12-Day Scandal on the pages of the Sentinel didn’t come until Day 5, a 2-inch item under the headline “Nothing New in Investigation” placed on Page 3.

It hit the front page on Day 7, below the fold, the series of bold-faced headlines running longer than the meat of the story itself:

Board of Aldermen Discharged Officers Phelps and Gregory

This in Addition to Earlier Action on Sergt. Cofer

Committee Found No Evidence Reflecting On Any Other Members of Force

Probe Was a Thoro One

And like so many political scandals, this one died with a whimper.

A couple years later, the Journal would buy the Sentinel and Martin was named editor of both, a position he held until 1952.

A new mayor, George W. Coan, came on in 1929. Ardmore remains, and the house still stands at No. 1824.

Prohibition ended for all US states in 1933, and Martin himself lasted until 1957.

He died in Winston-Salem and is buried in Forsyth Memorial Park; he likely carried there with him his grudges from the 12-Day Scandal.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Winston-Salem Mayor Thomas Barber never gave a quote to the Journal.

” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/mayorbarber.jpg?fit=200%2C300&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/mayorbarber.jpg?fit=200%2C300&ssl=1″ data-recalc-dims=”1″>

Winston-Salem Mayor Thomas Barber never gave a quote to the Journal.

” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/mayorbarber.jpg?fit=200%2C300&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/mayorbarber.jpg?fit=200%2C300&ssl=1″ data-recalc-dims=”1″> Downtown Winston-Salem in 1925

” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/downtown1925.jpg?fit=300%2C178&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/downtown1925.jpg?fit=600%2C356&ssl=1″ data-recalc-dims=”1″>

Downtown Winston-Salem in 1925

” data-medium-file=”https://i2.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/downtown1925.jpg?fit=300%2C178&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i2.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/downtown1925.jpg?fit=600%2C356&ssl=1″ data-recalc-dims=”1″> Members of the Winston-Salem police motorcycle squad in 1928.

” data-medium-file=”https://i1.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/police-motorcycles-1928.jpg?fit=300%2C182&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i1.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/police-motorcycles-1928.jpg?fit=510%2C310&ssl=1″ data-recalc-dims=”1″>

Members of the Winston-Salem police motorcycle squad in 1928.

” data-medium-file=”https://i1.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/police-motorcycles-1928.jpg?fit=300%2C182&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i1.wp.com/triad-city-beat.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/police-motorcycles-1928.jpg?fit=510%2C310&ssl=1″ data-recalc-dims=”1″>

“WM Cofer”, as he is referred to in the story, was my great grandfather and I know the story well.

Fascinating. We’d love to hear more about it.