Joe Strummer, the de facto leader of the Clash, declared, “I think people ought to know that we’re antifascist, we’re anti-violence, we’re anti-racist and we’re pro-creative. And we’re against ignorance.”

The music of the Clash, which burst across the world like an illuminating flash of lightning from 1976 to 1982 (the aptly titled 1985 album Cut the Crap doesn’t count), has never sounded more vital and current than today.

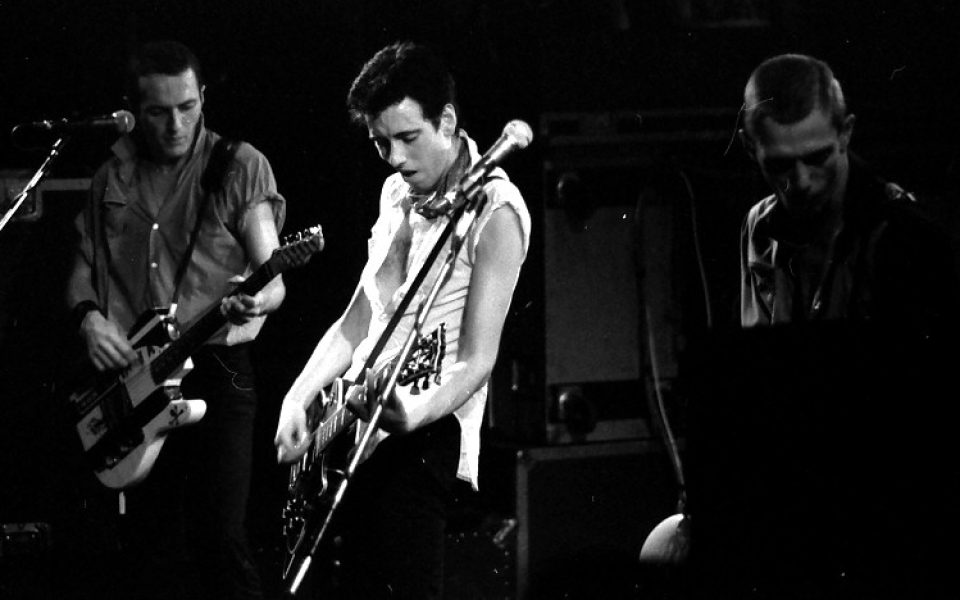

An English band that copped the loud and fast sound of American groups like the MC5, the Stooges and the New York Dolls, the Clash cut their hair and sonically leveled the bloated rock-and-roll conventions of gratuitous guitar solos and outsized egos when they emerged on the scene.

In a way, it makes sense that the Clash would be relevant again. On the eve of Conservative Party leader Margaret Thatcher’s election as prime minister, English society felt like it was at a dead end. The avowedly fascist National Front was ascendant and making its presence felt in the streets.

The Sex Pistols, who set the punk template and came first, sang, “There’s no future, no future, no future for you.” The Clash, meanwhile, conceived and modeled a youthful rebellion that promoted values of community, class solidarity and Third World revolution (they even named their 1980 triple album Sandinista!). The semi-fictitious documentary film Rude Boy includes a scene with Strummer arguing socialism to the band’s roadie, a wayward guy flirting with the far-right politics of the National Front. In fact, Strummer’s older brother, who committed suicide, had been a member.

We need the Clash’s music now more than ever as an antidote to the soul-crushing nationalism, extreme wealth inequality and reckless international brinksmanship that rules the world.

From the blistering class rage that fuels the first two albums to the kaleidoscope fusion of ska, rockabilly, funk and disco that radiates from the brilliant London Calling and Sandinista! albums and the anguished pop poetry of Combat Rock, the Clash left an unparalleled body of music. A 1982 concert recorded in Kingston, Jamaica that’s available on YouTube captures the exhilaration and sonic fearlessness of the Clash’s music at their peak. A 10-minute sequence through the kinetic funk of “The Magnificent Seven,” the feverish reggae of “Armagideon Time” and off-kilter intensity of the band’s cover of New Orleans R&B pianist James Booker’s “Junco Partner” is Exhibit A for the Clash’s MO. The fact that all three songs are delivered with raw, punk energy makes them all the more astonishing.

The Clash made a lifestyle out of their egalitarian politics, inviting fans backstage after every show, playing five-night runs at smaller venues to avoid stadiums and high ticket prices, and selling their double and triple albums for the price of one. They practically lived together, writing music and recording in a sustained burst of creativity and mayhem. In hindsight, it’s no wonder that they were broke and hated each other by the end. And when the band collapsed, it’s understandable that the individual members struggled on their own to make music one-tenth as vital as the Clash.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply