About a week ago, my parents returned from a short vacation to Canada and New York City. It was my mom’s first time in Quebec and my dad’s first time returning to the area in almost three decades. They were visiting an old friend of his, from the days when Dad was still an undocumented immigrant — before he was a father, before he had met my mom, before he came to call the US home.

He still has his original green card from those days.

It looks nothing like the kind of cards issued to immigrants today. The modern ones say something like “United States of America Permanent Resident.”

His reads: “Resident Alien.”

It’s flimsy, and the laminate is peeling off the edges. He looks so young he’s almost unrecognizable, but his signature at the bottom of the card remains the same. His fingerprint is fading.

My mom keeps telling my dad to get a new green card because the one he’s kept for decades gives them trouble when traveling overseas. It’s legit; it’s just rare — so old that it doesn’t even have an expiration date. He says he doesn’t want to get a new one.

And after giving it some thought, I get it.

The card isn’t just a weathering piece of cardstock wrapped in plastic. It’s a memento. A valuable trinket of the life he’s lived until now. Of the years of running around and traveling, searching for stability before he met my mom and had me and my sister. It’s an homage to the struggles and triumphs he faced as a young man facing the unknown for the first time.

My dad came to the US at the age of 18 to visit his uncle in Buffalo, NY. He fell in love with the country as an impressionable, rebellious teen and decided that he would one day come back. After teaching himself English through textbooks, radio programs and countless play-throughs of his Eagles, Chicago and Simon and Garfunkel records, he returned four years later to Boston, a city where he knew just one person, a restaurant contact, and was put in charge as the manager of a Benihana because he fit the part. He once told me about his first shift there, just standing in the middle of the dining room smiling when a woman came up to ask him where the restroom was. He didn’t understand her.

Six months into the job, he was found by immigration officials and was told he had to leave the country. The management at Benihana sent him on a plane to Canada where he was immediately approached by more immigration officials who sent him right back. He eventually made it to his uncle in New York and slipped through the Canadian border posing as a tourist at Niagara falls. From there, he traveled back to Quebec and made friends with the man with whom he reunited just a week ago. He lived there for about six months before going back to Japan to obtain the green card he still keeps in an office cabinet at home.

Once he was classified as a resident alien, he came back to the US and bounced from city to city, job to job. Throughout my childhood, he would drop hints and memories of places he had lived, jobs he had held. He tended bar in Boston for a while, he lived in Las Vegas and then in LA as a guide for Japanese tourists. He worked in a restaurant in Detroit before deciding the weather didn’t agree with him and then he packed up and moved to New York where he met my mom years later.

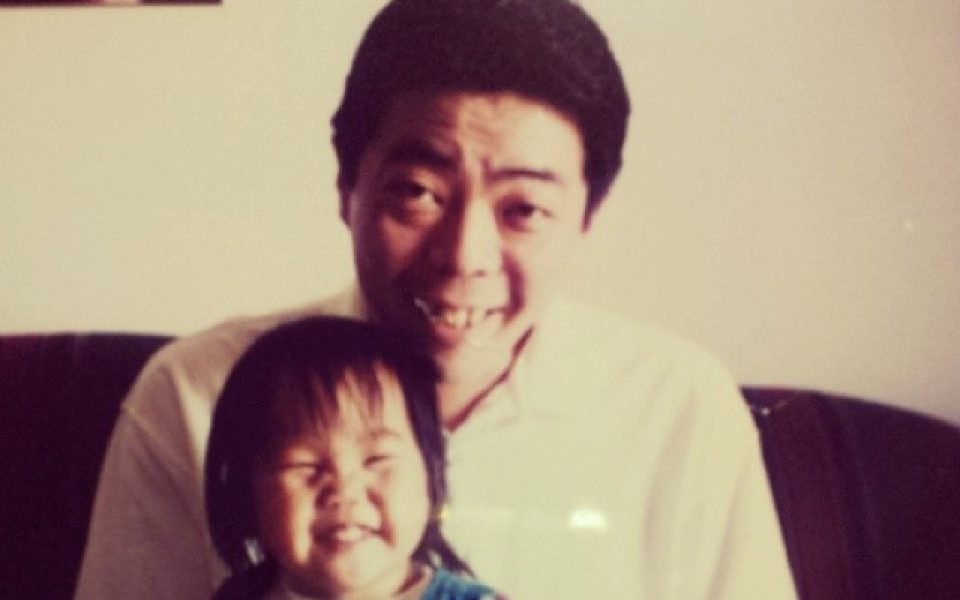

In the 26 years that I’ve known him, I’ve only known Tokumitsu Matsuoka as my dad. I didn’t know about his whole life before I came into the picture until about a year ago when I sat him down and he told me this story while sipping his usual whiskey and oolong tea concoction as I took notes.

Last summer, my parents closed the hibachi restaurant they had run for two decades and finally retired. He had been working for about 40 years straight.

This year when I asked him what he wanted for Father’s Day, he said he wasn’t sure and that he would let me know. He asked if he could bundle whatever gift he decided on with his birthday in September. I told him of course.

The thing is, he could bundle this holiday with countless birthdays and Christmases and it wouldn’t be enough. It wouldn’t be enough for me to say thank you for sticking it through even when he wanted to quit. It wouldn’t be enough for me to say thank you for giving me and my sister a life much easier than his own. But that’s what being a good parent is I guess. Doing all the things to give your kids a better life and asking nothing in return. We just got extremely lucky.

Happy Father’s Day Papa, thanks for everything.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply