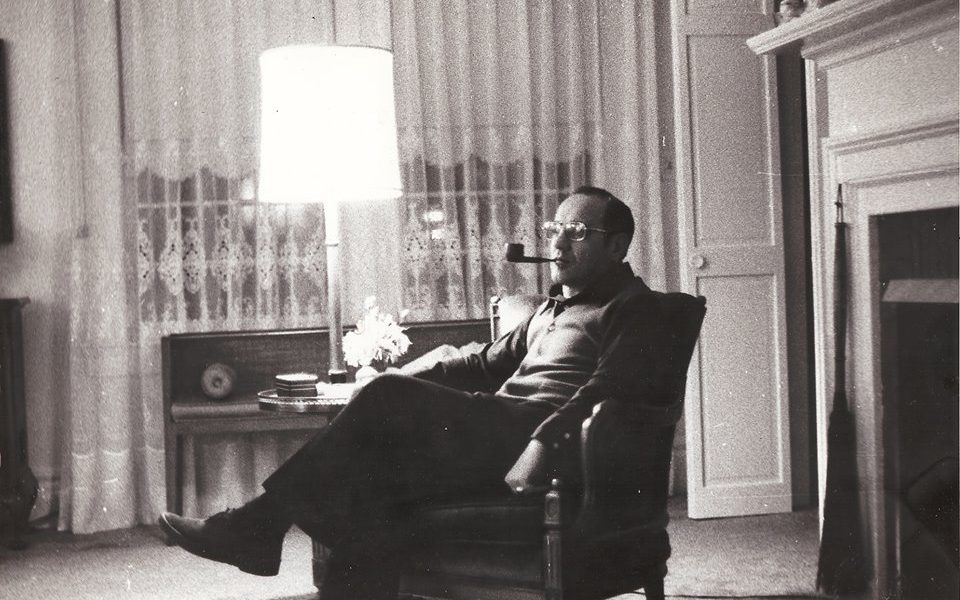

We lost PaPa the first time more than 10 years ago, when dementia and alcoholism conspired to rob the man of his final act in a good, long life.

So by the time we truly lost him, just a few days shy of his 98th birthday, most of us had already mourned for his soul.

I traveled to New Jersey by plane, train and automobile, joining those of us who were left to bury him in a plot in Rockaway, purchased long ago. There he would join my grandmother and her parents in a small hillside cemetery filled with gravestones bearing Italian names.

He outlived his six brothers and sisters, including an identical twin, Carmelo, who died almost 50 years ago, when I was in the fourth grade. I remember my PaPa bringing me to the mausoleum where his brother was interred shortly afterwards, the only time I ever saw him cry.

In PaPa’s eulogy, delivered in the same Morristown church where he was baptized and attended mass his whole life, my Uncle Tom referred to his “underprivileged upbringing.” He was the son of immigrants, Pellegrino and Brigida Pagano, a less-than kid who worked his way to an Ivy League education and a thriving dental practice through the Depression, a world war and an era of discrimination against Italian Americans. His admission to Springbrook Country Club in the 1950s was scandalous, no matter that he was a professional and a war veteran.

PaPa went to Germany as an army dentist at the end of World War II, fell quickly under Gen. George Patton’s command and went to Dachau shortly after it was liberated, bringing home stories of the piles of jewelry, human hair and baby shoes that he saw, as well as an enormous Nazi flag plundered from a stadium after US occupation began.

My uncle, a former school superintendent, quietly donated the flag to a traveling Holocaust museum, but he keeps the stories intact.

Over penne Bolognese and chicken piccata at Portofino’s in Morristown, one of PaPa’s haunts, those of us who were left traded these stories like shared artifacts, some unearthed for the first time.

We digested it all in the ride back to my aunt’s house near Princeton, our moment of closure for the man we loved and who loved us in return.

“I wish I asked more questions,” my mother said from the back seat.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply