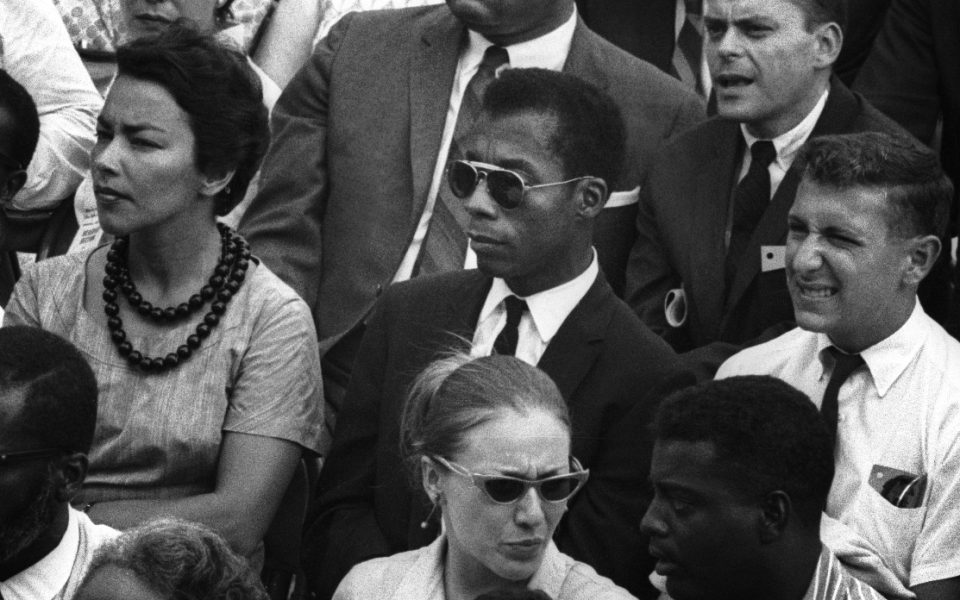

The incident outside of a high school in North Carolina is what finally provoked James Baldwin to return to the horror he’d left in the United States. When he encountered photographs of the episode in newspapers at every kiosk on a Paris boulevard, they devastated him.

Baldwin, the influential African-American author and social critic, once said on “The Dick Cavett Show” that he had left the United States to release himself “from that particular social terror, which was not the paranoia of my own mind, but a real social danger visible in the face of every cop, every boss, everybody.”

When Baldwin saw these images, he later wrote: “It made me furious. It filled me with both hatred and pity, and it made me ashamed.”

The photographs showed Dorothy Counts, a 15 year-old black student, as she approached the doors of Charlotte’s Harding High School. She was one of four black students to integrate the city schools in Sept. of 1957, less than 60 years ago.

All around her, pressing in on three sides, was a mob of white people — aggressive, reviling and dangerous — tormenting the young girl. Reports say that the long, red-and-yellow dress that her grandmother had made for Counts’ first day of school was covered in spit.

“Some one of us should have been there with her,” Baldwin wrote, ruminating on his mindset in France. “I could simply no longer sit around Paris discussing the Algerian and the black American problem. Everybody else was paying their dues. And it was time I went home and paid mine.”

I Am Not Your Negro, an Oscar-nominated documentary by Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck, begins with a surprising opening credit: “Written by James Baldwin.” Though the writer has been dead for nearly 30 years, his television appearances, recorded speeches and his writings — brought to life by Samuel L. Jackson — compose nearly all of the film’s spoken content.

Most prominent of Baldwin’s work in the documentary is his unfinished manuscript “Remember this House,” only 30 pages long by the time of his death. The incomplete memoir tells the story of Baldwin’s personal recollections of and friendships with civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. as he considered their lives and mourned their assassinations.

“I want these three lives to bang against and reveal each other, as, in truth, they did,” Baldwin wrote to his literary agent.

Throughout the film, Peck intercuts footage of racist violence, protest and police brutality in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, some indistinguishable from acts from the past few years.

Viewers hear Baldwin’s eloquent contention — often half a century old — as the contemporary images and videos roll.

“You watch the corpses of your brothers and sisters pile up around you, not from anything they have done — they were too young to have done anything!” Baldwin cries, while the images and the birth and death dates of Tamir Rice, Aiyana Jones, Darius Simmons and so many more pass by silently, one after the other.

[pullquote]I Am Not Your Negro runs at Aperture Cinema in Winston-Salem from Friday through March 2. A special screening on Saturday at 1 p.m. includes a discussion of Baldwin’s book The Fire Next Time presented by Scuppernong Books[/pullquote]

Understandably, there is more to unpack in the life of James Baldwin than even this profound documentary can undertake. Notably absent is any substantial conversation of Baldwin’s gay identity.

Peck succeeds in exhibiting the persistence of the oppression towards African Americans in the United States. But Baldwin’s sexual orientation played too important a role in his philosophy and in the triangulation of his life with others in the Civil Rights Movement to nearly wholly exclude it from the film.

Baldwin’s writing and social critique extend beyond racial oppression to all of the oppression imposed by dominant American society, and even to the disapproval and persecution within oppressed communities. Some theorize that Baldwin’s sexual orientation created distance between himself and King. Whether or not there’s truth to that theory, the documentary barely addresses Baldwin’s sexuality — a regrettable absence regarding the life of a man whose insight played an important role in the intersection of black and LGBT existence.

As the film’s credits roll, viewers hear contemporary hip-hop artist Kendrick Lamar’s track, “The Blacker the Berry.” While this choice celebrates Lamar, one of the great artists of a new generation, the song’s contents — segregation and sabotage; gentrification, generational hatred and genocide; institutionalism, Trayvon Martin and much more — suggest that the filmmakers don’t shy from the persistence of oppression, even at the film’s conclusion.

The lives of Baldwin and Lamar meet in the expression of similar and enduring persecution. Their experiences bang against and reveal each other, as, in truth, the lives of so many in the black community continue to do, year after year, one after the other.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply