The most important construction in Greensboro isn’t a high-rise or a performing arts center. It’s a road that will change everything.

“The big key is the loop” says Greensboro City Councilman Jamal Fox, “The loop and Phase II.”

Fox represents District 2, where what he claims is the most crucial section of the Greensboro Urban Loop is in the early stages of construction.

“You tell me another project in the entire city that’s going to bring people in and out of the city every day.”

Maps of his district fill the wall space in his modest office in Melvin Municipal Office Building, most of them concerning the outlying area on the northeast fringe of Greensboro. He’s got digitized maps tilted against the walls, stacked atop satellite-image maps and digitally designed concept maps. More maps, run off a computer printer, hang at eye level on the shelf above his desk. A gold ceremonial shovel crusted with dirt leans into the corner.

Phase II, also known as the Cone Boulevard Extension, will connect vast, isolated tracts in his district to the rest of the city and the state, bringing opportunities for development to a part of the city that hasn’t seen much attention since talk of reopening the White Street Landfill died down.

It should all be done by 2022, and though most of the loop itself is already functioning, the last few miles — the most important ones, according to Fox — require a lot of heavy lifting before completion.

***

The boulevard named for the Cone family who brought large-scale industrialization to Greensboro begins, fittingly enough, at a McDonald’s on Battleground Avenue.

From there it quickly moves eastward, over Lawndale Drive and into the fringe of New Irving Park, where a median splits the road into two ample lanes on each side.

It curves past Buffalo Lake on its way through town, giving access to communities old and new on either side: Kirkwood, Irving Park, O Henry Oaks, the Mill District, Rankin Farm. It unloads at the juncture of Highway 29 and the old Carolina Circle Mall, now a mega-strip mall anchored, also fittingly, by a Walmart.

Cone Boulevard itself is part of a loop, joining at Battleground with Benjamin Parkway and then Wendover Avenue to encircle three-quarters of the city’s core, catching downtown in a pincer movement, sort of a Pac-man bite. The Wendover artery connects the interior with points east, through Burlington, and west, through northern High Point. Benjamin spins off into Bryan Boulevard, an expressway opening up the northwest part of the city running directly to the airport.

But Cone, after connecting with Highway 29, continues on for a promising mile and then, just after 16th Street, unceremoniously stops at a stand of temporary orange hazard markers holding back the wilds of the northeast fringe of the city.

Now Cone Boulevard is awakening, greeting the scant vehicular traffic with groans of trucks and glimpses of freshly turned earth. When it finally fulfills its destiny in 2022, it will connect with Interstate 840, which is the official name of the Greensboro Urban Loop.

***

The urban loop is a tweak to the Interstate Highway System, which itself is perhaps the most important component of the nation’s infrastructure, envisioned as far back as 1916 and finally built by President Dwight Eisenhower in the 1950s. Interstate 85 claimed its original route along the southeast edge of Greensboro in 1960, with Interstate 40’s southern parabola coming on around the same time.

By then the project’s first urban loop — the 695 Beltway around Baltimore — was already open to traffic.

The urban loop is both a concession to the reality of urban traffic and a solution to it. The freeways allow vehicles — trucks, mostly — to pass by without getting caught in high-density traffic. At the same time, a loop pulls traffic from its interior, easing congestion on a city’s arterial flow.

And with the cars come economic activity. A loop creates points of ingress to the city, with exits populated by gas stations and convenience stores, strip malls, hotels and motels. Residences go up, first townhomes and condos, and then full-fledged commuter neighborhoods strengthened by proximity to the highway.

A complaint with urban loops is that they encourage sprawl and car travel, dilute municipal services and create further insularity among communities. But in Greensboro, where all of those things already exist, the loop may have the effect of reining in the city.

From the bird’s eye, the map of Greensboro looks like a turtle that’s been squashed under the wheels of a tractor-trailer on the highway. A barrier of lakes to the north screens the city from Summerfield and Browns Summit. Piedmont Triad International Airport defines the west end while growth to the south and southwest is blocked by Pleasant Garden, Jamestown and High Point. Only the northeast corner of the city has enough undeveloped and unincorporated land for growth. There are more creeks than roads out this way, in the acute angle formed by Highway 29 and Wendover Avenue, and the Cone Boulevard extension will run right through the heart of it on its way to the loop.

Greensboro’s partially constructed loop already shaves 20 minutes or so off the drive from the airport to the southern reaches of the city. Truckers taking Interstate 85 can now route around the city instead of driving through it. When complete, it will create a route through the north from the airport with spokes at Battleground, Lawndale and Elm leading to downtown, and give residents of those longstanding neighborhoods easy access to the highway.

***

Most of it is already done.

About 25 miles of the 40-mile lasso that will encircle Greensboro has already been constructed, reclaimed or re-routed since City Manager James Townsend hired a street engineer named Willard Babcock to deal with the huge influx of cars on city streets in 1953.

Babcock’s plan, adopted by city council in 1954, overlaid a set of concentric circles — loops — around the city that included the one now formed by Cone and Benjamin. The Babcock plan gave us Wendover Avenue and elevated Holden Road from a country lane into a main artery on the west side and anticipated the urban loop, which came to be known as Painter Boulevard, decades before it seemed necessary. The plan also laid out a blueprint for the city’s development that would serve the next 50 years.

The state got serious about the urban loop for its third largest city around 1989, finally approving a plan in 1995 and finishing construction on the first segment, a two-mile stretch connecting Wendover with 40/85 in the west, by 2002.

Today the the loop begins — or ends — at Bryan Boulevard at the northern end of the airport, with a southerly stretch that includes a rare highway stop sign before entrance to Interstate 73, one of the newer roads in the system that will eventually run from Myrtle Beach through West Virginia but which for now is confined to a stretch from Greensboro to Randleman.

Here, 73 crosses the westernmost edges of Friendly Avenue and Market Street and then cuts across Interstate 40 through the Adams Farm area. This piece of 40 along the south side of the city was briefly renamed Business 40 and the interstate rerouted. But after complaints about confusion from drivers, the state got permission from the feds to change it back.

Now 73 merges with Interstate 85 where the loop continues its counterclockwise roll, along the southern border of Greensboro and deep into the rural space of Pleasant Garden before turning north through McLeansville. Here, after 24 miles of loop, proper signage for Interstate 840 marks the last few miles, which dump off into a very easterly part of Wendover Avenue, just a quarter turn from the planned Cone Boulevard interchange.

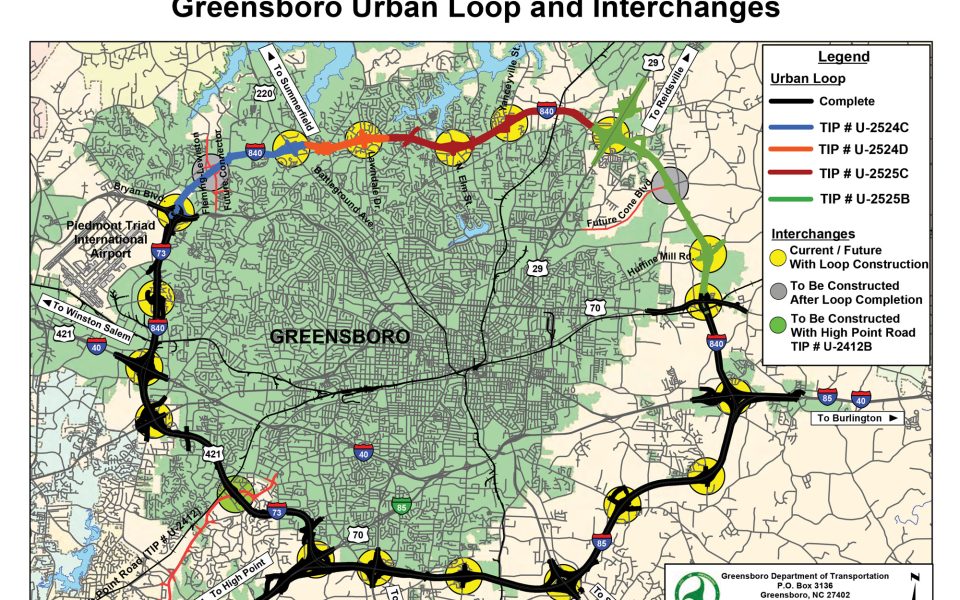

Gov. Bev Perdue gave the final go-ahead for Greensboro’s urban loop in 2011, releasing the state highway funds necessary to complete the northern stretch. The four segments begin at the airport, then cut across Battleground, Lawndale, North Elm Street and Yanceyville, connecting with Highway 29 and that final northeastern stretch.

You can see the T-shaped risers coming up on the North Battleground and Lawndale in the northwest.

In the relatively uncharted territory of the northeast, the westbound lanes already announce themselves above the tree line out by Rankin Mill Road and Hines Chapel Road, two of the three that define the wide open space that includes the White Street Landfill where, on a clear day, you can see the cranes off in the distance from the top of the tallest mound.

The roads don’t always connect out here; some of it is the city and some isn’t. Wide patches of clear-cut rubble stand among trailer parks and small urban farming operations. One fenced-in yard holds about a dozen sheep. Campgrounds of concrete and rebar and fresh-turned dirt bloom in the spaces between cable cuts and homesteads while, just a couple of miles and what seems like a world away, the city sleeps.

***

This sort of development in the northeast has been on the table for decades, its halting progress spurred, Councilman Jamal Fox says, by demographic shifts and changing traffic patterns.

“Everybody started using 29 to get to DC and Virginia,” he says. “And we got folks stuck in commutes out there that have to go through town to get anywhere in our city.”

He moves around the maps that line his downtown office, repeating the mantra — SIF — that guides his efforts.

“SIF,” he says. “Strategic, intentional and focused. What I would hate is if [the loop] were to come through and we weren’t prepared for it.”

By the time the loop is finished in 2022, it will affect thousands of acres along the north side of town, particularly pockets of undeveloped land at the Battleground interchange and the raw terrain that will eventually be traversed by Cone Boulevard.

Fox’s vision includes a central park off Cone with athletic fields and trails that build on the existing Keeley Park, new residences and commercial properties.

“I believe this area can hold four hotels,” Fox says, angling a map of a planned infill development so it catches the light. It’s slated to be built in the wedge formed by Cone and 29: a couple hotels, a retail strip mall, a movie theater, a bowling alley.

“I said, ‘We need a bank out here,’” Fox says. “We need some meaningful projects. We have the rooftops. We’re trying to make it an entertainment area — you can shop here, you can play here, you can invest here, you can live here.

“You show me another geographic location in Greensboro that has this great of an opportunity,” he continues.

Investors have been online for years now, waiting for the roads, he says.

Near the eastern leg of the loop, in the crook where Business 85 meets 840 and Interstate 40, the McConnell Center, a 140-acre industrial park, broke ground in 2008. Its only current tenant is an O’Reilly Auto Parts distribution center. Developer Roy Carroll built Innisbrook Village Apartments just across the street, and Marty Kotis has a 28-acre parcel near where the loop runs into Wendover — by 2022 it will be a $25 million shopping center. Greensboro holding company AnnaCor Properties has 42 undeveloped acres nearby.

The city owns property out there too: the Sportsplex, the wastewater treatment plant and the White Street Landfill. The Cone extension will run right through another parcel that, right now, is nothing but trees.

***

In all, the Greensboro Urban Loop should soak up about $1 billion — more if implementation doesn’t keep up with inflation. The leg running along the northeast corner from Wendover to Highway 29 comes with a price tag of $112 million, paid for with state DOT funds. But the Cone Boulevard Extension, with a relatively low cost of $11 million, remains unfunded. It’s the final hurdle in the rejuvenation of this corner of Fox’s district.

“When you talk about transportation funds,” the councilman lets loose a long exhale. “That’s a tough one. It’s a city project, but at the same time it’s a state road.”

The Cone interchange isn’t scheduled until after that section of the loop is completed in 2018, and will perhaps be active by 2022, 70 years after the Babcock Plan was crafted to bring Greensboro into the modern world of automotive transportation.

The original architects of the plan knew they likely wouldn’t be around to see the fruits of their handiwork, but the young councilman, who turns 28 this month, thinks he might see the results of his labor.

“I plan to still be here in 50 years,” he says.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

There is no interchange planned for Cone Boilevard and the Urban Loop.

Not so. It just hasn’t been funded yet. The point is that it WILL be funded and built….

Mr. Perkins! I knew I should have interviewed you for this piece.

But the DOT map indicates otherwise, that the interchange is scheduled for construction after completion of the loop.