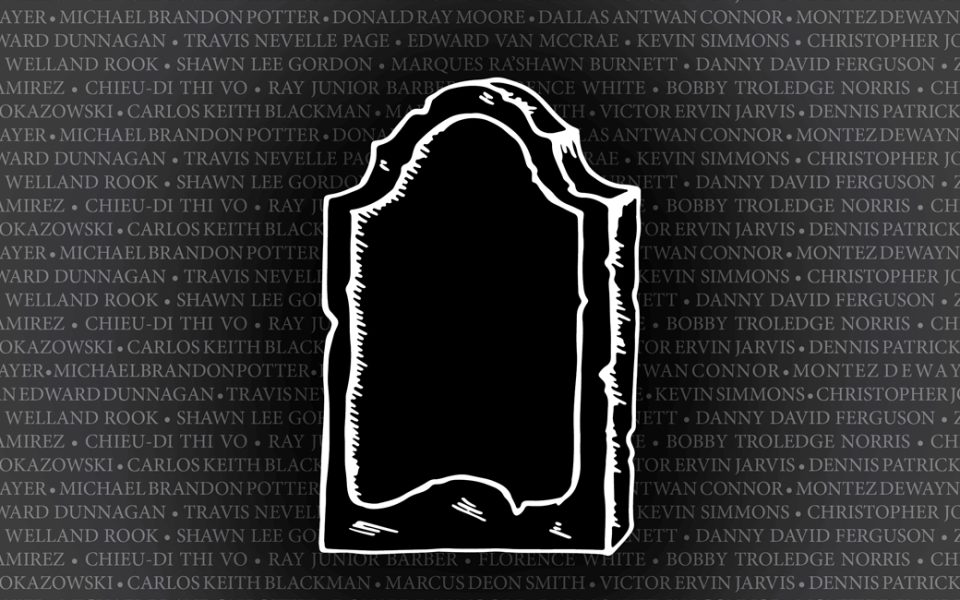

In the past 10 years, 25 people have been killed by law enforcement officers in Guilford and Forsyth counties.

Edward Van McCrae was riding in the backseat of an older-model Toyota Camry on March 30, 2018 when the car was pulled over by a Winston-Salem police officer.

The officer turned his attention to McCrae, asked him what he was holding in his hands and then told McCrae to get out of the car. A few minutes later, McCrae was shot and killed by the officer.

Less than six months later, Marcus Deon Smith was hogtied and killed by police in Greensboro.

While McCrae and Smith’s deaths took places within a few months of each other, a review of data by Triad City Beat found that at least 25 people have been killed by police or sheriff’s department officers from 2010 to 2020 in Guilford and Forsyth counties. (A publicly available spreadsheet of all of the deaths can be found here.)

As the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police reinvigorated the Black Lives Matter movement this past spring, law enforcement killings have garnered renewed interest across the Triad, and indeed across the nation.

A domestic-disturbance call involving a suicidal individual; a suspect wielding a knife; a traffic stop with a “suspicious” backseat passenger. These are just a few examples of situations that led to people being killed by law enforcement officers in the Triad since 2010.

For the purposes of this article, TCB reviewed data compiled through Fatal Encounters, an online database of killings by law enforcement officers that was compiled by journalist D. Brian Burghart. TCB focused on incidents from the past 10 years and only included incidents in which law enforcement officers were directly involved in the deaths of individuals. For example, incidents in which individuals fled police in a vehicle and died by collision are not included.

The 25 instances logged and analyzed by TCB found that both men and people of color, particularly African Americans, were overrepresented as victims of law enforcement violence. TCB’s data parallels national data which shows that Black people are killed at a significantly higher rate than whites. According to a report by the Washington Post, Black people are killed by law enforcement at more than twice the rate of white Americans.

Despite making up 28 percent of the population of Forsyth County, Black people accounted for 67 percent of deaths at the hands of law enforcement. In Guilford County, Black people made up 44 percent of the deaths, despite accounting for only 35 percent of the population.

In both counties, white individuals were disproportionately underrepresented in police killings. In Guilford County, white individuals made up 38 percent of the deaths despite making up 56 percent of the population, and in Forsyth county, 22 percent of deaths involved white people despite the same demographic making up 67 percent of the population.

Analysis by TCB also found that a majority of the officers involved in the fatalities were white males. A number of officers’ race could not be identified. Two officers were Black females and one was a Black male.

When is deadly force used?

According to North Carolina General Statute 15A-401(d), officers are justified in using force when “the officer reasonably believes the force is necessary” and “to the extent the officer reasonably believes the force is necessary.”

In the 25 cases analyzed by TCB, the situations in which officers were called to the scene ranged from domestic disturbance calls, mental health crises, traffic stops and crime calls.

In Forsyth County, most of the situations involving the victims were criminal in nature, while in Guilford County, mental health-related issues and domestic calls made up the majority of instances that led to the deaths.

A 2016 article published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine analyzed 812 deaths at the hands of law enforcement in 17 states from 2009 to 2012 and found the largest category of incident involved “mental health or substance-induced disruptive behaviors” which accounted for 22 percent of cases. The next most prevalent type was categorized as what the report calls “suicide by cop” in which victims exhibit suicidal behavior directed at law enforcement to elicit use of lethal force. The report explains that suicidal intent could include suicidal threats during the incident, a suicide note or prior expression of desire to be killed by law enforcement. These accounted for 18 percent of deaths. Intimate partner violence made up 14 percent of incidents and 6 percent was categorized as “unintentional deaths due to law enforcement action.” The article also found that in 94 percent of cases, the primary cause of death was a firearm.

The incidents in Guilford and Forsyth counties analyzed by TCB from the last decade found that in 18 of the 25 cases — or in 72 percent of cases — individuals died after being shot by officers.

On May 25, 2011, Deborah Moore called 911 and told the dispatcher that her husband, Donald Ray Moore, was acting erratically. When police arrived at their home in Winston-Salem, they found Moore, a 64-year-old Black man, barricaded inside. Police exchanged gunfire with him for almost three hours. In an effort to get Moore out of the house, police used an armored vehicle to knock out the windows in the living room and two bedrooms of the house. The vehicle also broke down the garage door. In the end, Moore was shot and killed by a sniper. In an article by the Winston-Salem Journal from June 2011, Moore’s wife, who called the police, said her husband had a history of mental illness and questioned why they didn’t call in a mediator from a mental-health association.

“He may not have been on his medication,” Moore said. “I don’t think it was necessary to do that to him. It’s wrong. It’s just wrong.”

The article goes on to say that many of Moore’s relatives believed excessive force was used during the incident. In the months that followed, the city hired a contractor to repair Moore’s house.

Five years later in Greensboro, Christopher Michael Tokazowski, a 43-year-old white man, died after being shot by Greensboro police officers. Tokazowski’s wife filed involuntary commitment papers for her husband, who she said was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and ADD. When police showed up at the house to serve Tokazowski the papers, he armed himself with a shotgun and stayed inside the house. Special-response and hostage-negotiation teams were called, according to a News & Record report, and Tokazowski called 911 to complain that officers were surrounding his home. A short while later, Tokazowski came outside with the shotgun and pointed it at officers, according to then-police Chief Wayne Scott. At that point, officers shot and killed at Tokazowski. Officers also shot out the lights around the house and the rear tires of Tokazowski’s Jeep Wrangler. Tokazowski’s wife said in an interview with the N&R that if she knew that the police were going to kill him, she never would have called them.

The 2016 article from the American Journal of Preventive Medicine states that law enforcement frequently serve as the first responders in mental health emergencies and that officers in a study from three US cities reported responding to an average of 6.4 calls per month involving mental-health crises. The article also cited multiple scholarly articles in which officers reported feeling inadequately trained to assess and respond effectively to these types of calls. The 2016 article’s findings indicated that one in five of the deaths were directly related to issues with the victim’s mental health or substance-induced disruptive behaviors.

The Greensboro Police Department directives states that “agency personnel shall afford people with mental illnesses the same rights and access to police… as are provided to all citizens.” The manual also states that agency personnel receive training on how to interact with individuals with mental illnesses and that refresher training is provided to all appropriate personnel on an annual basis. The training, according to the directives, includes strategies for recognizing mental illness behaviors, methods for accessing community resources and guidelines for responding to situations.

Kami Chavis, a professor of law and the director of the criminal justice program at Wake Forest University, said she doesn’t believe law enforcement should be the first responders for mental health crises.

“I think in general, there is widespread consensus that we don’t need an armed first responder in every situation,” Chavis said in an interview. “We can’t assume that every officer is going to be the best person to respond to a mental health crisis or deescalate a mental health crisis…. If an officer is called to transport someone who is having a mental health crisis and this person is not a danger to themselves or others, we need to be prepared to wait to bring that person peacefully to where they need to be.”

Many law enforcement departments enroll officers in crisis-intervention training, or CIT, to help reduce arrests for non-violent offenders with mental health concerns and to reduce use of force injuries. The Winston-Salem Police Department, Forsyth County Sheriff’s Department, Greensboro Police Department and Guilford County Sheriff’s Department have officers who have completed CIT training. However a 2019 article from the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law stated that CIT trainings can increase “officer satisfaction and self-perception of a reduction in the use of force” but that “no measurable difference in the use of force between officers with CIT training and those without it.”

In December 2019, Greensboro City Council approved a plan to create a separate response team for mental health crises. The idea for the Behavioral Health Response Program began after the death of Marcus Deon Smith and consists of a team of mental health professionals. In the case of 911 calls, dispatchers would send police, and the team could be called for backup by the responding officers or could be sent by dispatchers simultaneously.

Councilwoman Michelle Kennedy told TCB that the response team, which is comprised of less than a dozen mental health professionals who are not employed by the police department, has assisted on 355 crisis calls since implementation in March.

Kennedy said the average response time of the team is about 19 minutes and they spend about 48 minutes at each engagement.

“You can’t arrest your way through mental illness,” said Kennedy, who has been a proponent of the program for years. “The way a trained mental health clinician is going to interact is going to look different than how a police officer will react.”

Kennedy said she believes most of the time police officers call the team when they arrive on the scene, but she hopes that in the future there won’t be a need for police to respond at all in certain cases.

“I want them to come out without officers because the presence of officers can be triggering a lot of the time,” she said. “We’re not there yet, but that’s the end game.”

While cases in which mental health played a factor in the deaths were prevalent among the 25 incidents, at least two occurrences involved a fatal shooting resulting from a traffic stop.

On Feb. 10, 2017, Carlos Keith Blackman was stopped by Greensboro police officers, who said he fled on foot. According to the police department’s press release, Blackman, who was Black, and the officers exchanged gunfire; Blackman was shot and killed by police. The press release and news reports from the time did not state why Blackman was pulled over or whether Blackman or the officers shot first. One officer, JR LaBarre, was shot and taken to the hospital but was said to be in stable condition at the time.

About a year later, in March 2018, in Winston-Salem, Edward Van McCrae, a 60-year-old Black man, was shot and killed after a police officer stopped a car that McCrae was riding in because of an expired registration sticker. According to the officer, McCrae was “acting suspicious” in the backseat and the officer, Dalton McGuire, asked McCrae what was in his hand. McGuire then told McCrae to exit the vehicle and lie on the ground. In body camera footage analyzed by TCB, McGuire then repeatedly tells McCrae to “stop reaching” for a gun and then yells, “Gun. Gun… don’t reach for the gun!” McGuire then fires four shots at McCrae, three which hit and kill him. The grainy footage makes it difficult to see the gun referenced by McGuire but in a presentation by District Attorney Jim O’Neill, McCrae could be seen lying on the ground while reaching for his back pocket. In a later frame, a small pistol is shown lying in the grass near a storm drain. O’Neill determined McGuire acted lawfully during the incident. In December 2018, the city settled a wrongful death claim with McCrae’s family for $20,000.

Other incidents that led to civilian deaths could be categorized as crime calls.

On Sept. 20, 2012, Danny David Ferguson, a 60-year-old Black man, was shot and killed after police were called onto the scene in response to a stabbing in High Point. Officers told Ferguson to drop the knife. After Ferguson ignored their commands and approached the officers, police shot and killed him. Less than two years later, on May 25, 2014, Montez Dewayne Hambric, a 26-year-old Black man, was killed by Winton-Salem police officer David Walsh after Walsh chased Hambric while responding to a stolen car report. According to a report by the Winston-Salem Journal, Hambric and Walsh became engaged in a physical altercation after Walsh Tased Hambric. Hambric grabbed the baton and initially walked toward Walsh before running away. At this point, Walsh drew his pistol and started pursuing Hambric, who came within five feet of Walsh and ignored Walsh’ commands to get on the ground, according to the police department’s news release. Walsh then fired one shot to the chest that killed Hambric.

In instances like these, in which suspects are armed, the situations get trickier, said Chavis, the professor at Wake Forest University. Because the law allows officers to use deadly force if they feel threatened, oftentimes they resort to violence if they see a firearm, whether it is used or not. But Chavis states that in North Carolina, civilians are allowed to carry both concealed and non-concealed weapons.

“Just because someone has a firearm doesn’t mean they are wanting to harm someone,” Chavis said. “Just because someone has a firearm doesn’t mean they should be shot on sight. It very much matters what they are doing with that firearm.”

Chavis also brought up instances in which white suspects who have killed others like Dylann Roof in South Carolina in 2015, and more recently Kyle Rittenhouse in Kenosha, Wis. in August, were both apprehended by police peacefully after killing multiple people.

“It’s not often the same for others who may be carrying,” Chavis said.

What happens to the officers involved?

In the 25 cases that led to the deaths of individuals analyzed by TCB, only one officer — JR LaBarre, who was shot during the Carlos Keith Blackman case — was injured. None of the officers involved in the incidents were killed. According to records kept by Officer Down Memorial Page, a website that tracks when law enforcement officers are killed, three officers have been killed in the last 10 years in Guilford and Forsyth counties. All were killed in automobile accidents; none were killed by suspects.

Public record requests obtained by TCB found that after law enforcement officers were involved in the death of an individual, more often than not, the officers did not face any disciplinary consequences and were found to be justified in their actions by the attorney general or district court judges.

In March 2014, Greensboro police Officer Tim Bloch shot and killed Chieu-di Thi Vo after she approached him with a knife during a domestic dispute call. Bloch was found to have been “justified in the level of force that he used that day,” according to then-Chief Wayne Scott. Bloch did not face any disciplinary charges and defended his use of force after the event in news reports.

Public records requests by TCB found a majority of the officers responsible for the deaths in the 25 cases remain employed by the same law enforcement departments and have even been promoted or have received annual raises since the incidents. Bloch resigned in December, about nine months after he killed Vo.

Guilford County sheriff’s deputies involved in a June 22, 2014 case in which Ray Junior Barber, a man who appeared suicidal during a domestic dispute call, was shot and killed, remained on the force and were subsequently promoted. Deputy SM Burns was promoted to lieutenant in 2019 and makes $72,252 in an annual salary while Deputy JR Stevens was promoted to sergeant in March of this year and makes $72,298 annually.

While officers don’t appear to have faced disciplinary charges in these cases, some have resigned in recent years after being involved in the death of a civilian.

Lee Andrews, a Greensboro police officer who was involved in the Marcus Deon Smith case, was given two pay raises before resigning in December 2019. The rest of the officers remain on the Greensboro police force with the exception of Robert Montalvo, who changed positions within the department and then retired in April of this year.

Most of the incidents in Forsyth County in which a civilian was killed by officers involved officers with the Winston-Salem Police Department. A public records request found similar trends to officers in Greensboro in which Winston-Salem police officers were given yearly raises and promoted after the incidents. In many of the Winston-Salem cases, Forsyth County District Attorney Jim O’Neill — who is running for attorney general against Democratic incumbent Josh Stein — ruled that officers acted appropriately in each case. In addition to the Edward Van McCrae case in which O’Neill ruled that officer Dalton McGuire “acted appropriately and lawfully,” O’Neill cleared officer David Walsh after the death of Montez Dewayne Hambric was classified as homicide by law enforcement in May 2014. A letter by the Forsyth County District Attorney’s Office released at the time states that the office determined that Officer Walsh’s use of force was justified and demonstrates that Walsh acted to protect his life and the lives of others in Winston-Salem.

According to data tracked by the Washington Post and Bowling Green University’s Philip M. Stinson, law enforcement officers kill about 1,000 people across the country per year, but since the beginning of 2005, only 121 officers have been arrested on charges of murder or manslaughter in on-duty killings. Of the 95 officers whose cases have concluded, 44 were convicted, but often of a lesser charge. One of the most recent and glaring examples was the decision by the Kentucky attorney general to charge one of the officers involved in the shooting of Breonna Taylor with wanton endangerment for shooting into a neighboring apartment. None of the officers involved were charged for Taylor’s death.

Only one case could be found by TCB in which a police officer was found guilty of a crime in which a civilian died. In November 2015, Winston-Salem police officer John William Leone Jr. pleaded guilty to misdemeanor death by motor vehicle after he ran a red light while on duty and crashed into Alan Edward Dunnagan’s truck in May 2015. Dunnagan died 10 days after the accident. A judge deferred judgment and ordered Leon to perform 200 hours of community service and by the end of March 2016 the officer was back on active duty. In a similar October 2014 case in Greensboro, Florence White, a 51-year-old Black woman, was killed after being hit by Guilford County Sheriff’s Deputy Philip Lowe’s patrol car. Lowe was not charged.

According to an article by the website FiveThirtyEight, prosecuting police is difficult because many instances of use of excessive force or lethal force is considered legal.

“If a civilian is displaying a weapon, it’s hard to charge a police officer if [the officer] with murder for taking action against that civilian,” said Kate Levine, a professor of law at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law. “And even if a civilian doesn’t have a weapon, it’s hard to charge a police officer if the [officer] can credibly say they feared for their life.”

Most law enforcement departments cite case law which set precedents for when police can use lethal force. The Greensboro Police departmental directives allow officers to use deadly force “when the officer believes the deadly force is necessary.” This includes instances to defend the themselves from what they perceive to be “use or imminent use of deadly physical force” or to prevent the escape or attempt to arrest those who present imminent threats of death or serious physical injury to others. The directives for the Winston-Salem Police Department read similarly to Greensboro’s. The Greensboro directives attempt to clarify the definition of “reasonable belief” by describing them as a “set of facts or circumstances that would cause a reasonable person in the officer’s position to believe it was actually or apparently necessary to use the force which was actually used.”

However, a number of use of force changes have taken place within the Greensboro police department in recent months including the banning of shooting at moving cars unless there are no other means to stop an imminent deadly threat, directing officers to use minimal amount of force necessary to arrest individuals, banning chokeholds absent the need to use deadly force, directing officers to verbally and physically intervene in any use of force that violates policy and finally, warning an individual before using force. The Forsyth County Sheriff’s Department updated its policy for prone restraint in July, adding that those who put in prone restraint “have to be placed in a sitting position as soon as possible.”

The FiveThirtyEight article goes on to describe other barriers to charging and convicting police including the fact that prosecutors work closely with police departments, which means they may be reluctant to jeopardize their relationship by pursuing cases against officers.

“Police officers are sympathetic in the eyes of the jury,” Chavis added. “They give officers the benefit of the doubt.”

One other way in which victims’ families sometimes seek justice is through civil lawsuits and settlements. In the case of Marcus Deon Smith, the Smith family filed a federal lawsuit against the city of Greensboro in April 2019 for wrongful death under civil rights law. The case is ongoing. So far, according to a report by the News & Record, the city has spent more than $213,000 in legal costs and attorney fees defending the city in the lawsuit. However, the FiveThirtyEight article stated that police misconduct settlements are not effective in keeping police accountable because police almost never pay out of pocket. Instead, the money comes from the cities or the police departments themselves. The article also states that it’s difficult to successfully sue a police officer because courts have granted them broad protections from legal liability for actions they take on the job, otherwise known as qualified immunity.

Still, Chavis said it’s concerning that in the 25 cases, no officers were disciplined, charged or convicted.

“I mean, what’s going on with the DAs?,” Chavis asked. “It could be that these 25 officers were justified, but it strikes me as odd that not one has resulted in a prosecution or charge.”

What now?

In the several months since the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, activists around the country have been calling for a defunding or complete dismantling of police departments and a move towards more social-service oriented response units for situations that regularly involve police.

Brittany Battle, a Wake Forest University sociology professor and a founding member of Triad Abolition Project told TCB that she wants to see the abolition of the police in the future.

“We know that abolition is a long-term project,” she said. “Part of abolition is developing a community of compassion and care that looks at justice in terms of accountability and not punishment. We want to create a community that is about transformation and restoration.”

Battle, who helped lead a 49-day occupation of Bailey Park in Winston-Salem to protest police brutality, said the first step to abolishing the police is defunding law enforcement departments.

“We have police doing jobs that they are not trained for,” Battle said. “We need to create services that actually function in a way that will help people will their issues.”

Activists with Greensboro Rising sent TCB a statement that outlined the ways they want to see law enforcement change in their city and county. In addition to a public apology for Marcus Smith’s family, the grassroots group also calls for the reallocation and defunding of the Greensboro police department to fund community programs, services and professional crisis de-escalators. The group also called for the city council to more permanently codify their resolution on use of force for the Greensboro Police Department. The resolution, which was initially discussed at a September council meeting, calls for the Greensboro Police Department to “revisit their use of force policies and form deep, meaningful, year-round relationships with local communities and their leaders….”

Activists with Greensboro Rising said it’s not enough.

“The city council isn’t voting on making any changes to how they hold officers accountable for using excessive force on residents,” they said in a written statement. “They are voting on congratulating themselves for the chief making a series of regulatory changes…. The use of force resolution has no permanence. It’s purely performative from GPD and can be changed at any time. This is unacceptable. When there is no check on police behavior, they are able to abuse citizens without impunity. We need civilian oversight independent from police. We will continue to push for legislation that ends physical violence and aggression by police when they engage citizens.”

Chavis of Wake Forest University said that she wants to see a national database that tracks police misconduct and that the data should be tracked at the state and local levels too.

“Having this data will help us better understand this police violence when it happens,” Chavis said. “It will be able to show us in what kind of situations and what kind of officers are using lethal force. Whether it’s only happening in larger cities like Raleigh or Charlotte or happening in smaller towns too. We need this info. Not having it really hinders us.”

Battle echoed Chavis’ sentiments and said that there needs to be more data to keep officers with multiple disciplinary issues accountable. Battle pointed to officer Derek Chauvin, who knelt on George Floyd’s neck, killing him in May. According to multiple news reports, Chauvin had 18 complaints on his official record and had been disciplined twice.

“He never should have been on the police force,” Battle said.

One of the other findings that came out of TCB’s investigation is that most of the law enforcement officers in Forsyth and Guilford counties involved in a case in which an individual was killed were white men.

Battle said that it’s not surprising that this was the case.

“Those disparities that we see are productions of the original law enforcement system,” Battle said. “In the South, it was slave patrols to police the movement of Black people to return runaway enslaved people back to plantations. That mentality and the white supremacist ideology underlies the system of policing now.

“Some people think this is about freeing people who are viewed as criminals, but it’s about appreciating the humanity of everyone and understanding that the punitive carceral system doesn’t serve any of us,” Battle continued. “Reallocating funds away from police departments will keep us all safer.”

To view a publicly available spreadsheet of all of the deaths, go here.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply