by Sayaka Matsuoka

Some of things conceived in 1996 have since slid into irrelevancy, like askjeeves.com, but the Vagina Monologues is not one of them.

Eve Ensler’s sassy, blunt play debuted the same year that parents all over the country hit stores for a Tickle Me Elmo, and unlike the creepy “Sesame Street” plush, the piece has continued to be successful throughout the years. The Vagina Monologues rose rapidly in popularity, quickly becoming an annual staple on college campuses and community theaters — both of which hosted the production in Greensboro last week.

There were only a few stray open seats at the Feb. 12 opening production put on by the Sherri Denese Jackson Foundation, a nonprofit for the prevention of domestic violence. The audience at the Stephen D. Hyers Studio Theater was predominantly female, with a handful of brave male souls scattered throughout. Brave because this show, as you may have guessed, talks a lot about a taboo subject — vaginas.

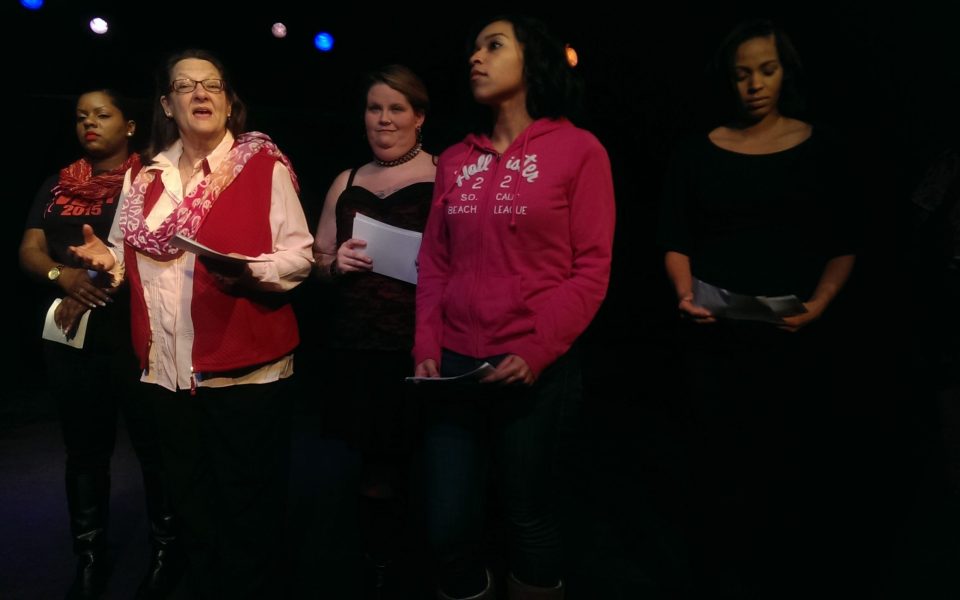

The show opened with an introduction by four women expressing a dire personal concern, the same mantra exhorted at productions each year; they were worried about vaginas. They worried what people thought about them or more so what they didn’t. They likened vaginas to the Bermuda Triangle.

“No one ever reports back from there,” one woman said. They lined up at the front of the stage and posed another awkward question: “What do you call a vagina?” They popcorned back and forth with both familiar and unfamiliar answers. “Pussy cat.” “Twat.” “Pooninana.” “Coochie-snorcher.” “Mimi.” The list went on and on, each name more ridiculous than the last. Although the play started with a slow, rocky start with some actresses stumbling over lines or repeatedly glancing at notes, by the third or fourth monologue, these women couldn’t be stopped.

The play sources its dialogue from Ensler’s interviews with women of different ages and races, and it is awkward to say the least. It’s in your face and direct, causing ample seat-squirming. As the show progresses however, the tension subsides and the repeated mentioning of perhaps the most intimate human body part becomes normalized. Rather than feeling embarrassed and uncomfortable, it becomes uplifting and educational.

The show takes on the rarely talked about issues surrounding female genitalia such as its appearance, pubic hair and sexual awakenings. One segment that immediately comes to mind is “The Flood,” performed by Michaeline Wright Parrish, an older white woman who recounts her first sexual experience in the back of a white Chevy Bel Air. Her impeccable acting and facial expressions elevate the humorous original script of the story and makes viewers empathize with her over-exaggerated sexual mishap. Other more serious and triggering stories in the play recount sexual assault and rape. But Ensler takes great care to execute the vignettes in a way that empowers and brings the right attention to the speakers.

While painful and at times heartbreaking, each of the monologues is an important lesson in feminist theory. In a short segment titled “My Short Skirt,” women strut onto the stage in skin-tight skirts and exclaim that their short skirts are “not an invitation” to sex and do not mean that they are “asking for it.” By having these women make clear, concise and straightforward statements, Ensler’s play plants mindful seeds that lead to increased awareness about rape culture and violence against women.

Other empowering speeches include “Reclaiming C***” which takes the “bad” word and ventures to reclaim it as a positive one in the female community. Rebecca Martin spells out the four-letter dirty word with clearly marked notecards, making for a hilariously bizarre, vulgar take on a spelling lesson. It even has viewers yelling the “obscenity” by the end of the segment.

In the midst of horrific and tragic stories like “My Vagina Was My Village” chronicling one woman’s traumatic experience in a Bosnian rape camp, pops of humor are sprinkled throughout, regularly lightening the show’s mood. “My Vagina is Angry” is a perfect example of this. In this rendition of the play, Pilar Benjamin storms onto the stage with overt sass and immediately begins ranting about why her vagina was angry. Everything from having to stuff cotton tampons up there to visiting the OB/GYN and dealing with “mean cold duck lips,” Benjamin executes the scene so perfectly that all of the members of the audience are still catching their breath after she stomps off the stage.

The bulk of the stories in the play remain the same annually but some have been tweaked since the first performance of the Vagina Monologues almost 20 years ago. Incorporation of transgender women in “They Beat the Girl out of my Boy — or So They Tried” and the rephrasing of the “The Little Coochi Snorcher That Could” are examples. In the latter, the original speech recounts a woman’s early sexual encounter with an older woman after getting drunk, which many viewers criticized as being statutory rape. In the original script, the monologue ends with the woman saying, “If it was rape, it was good rape.” This line has been taken out of more recent adaptations of the play and the age of the speaker has been changed from the original 13 to a more palatable 16.

Despite its few shortcomings in political correctness, the Vagina Monologues serves as an effective platform for awareness and stirs important dialogue when it comes to the sensitive topic of vaginas and the various experiences associated with them. The Vagina Monologues is fun, smart, sassy as hell and the only place where you can see Alice Mitchell, fully dressed in red lacy lingerie, act out, in painstaking detail, so many female orgasms and hear the word “clitoris” in the same span of 90 minutes.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply