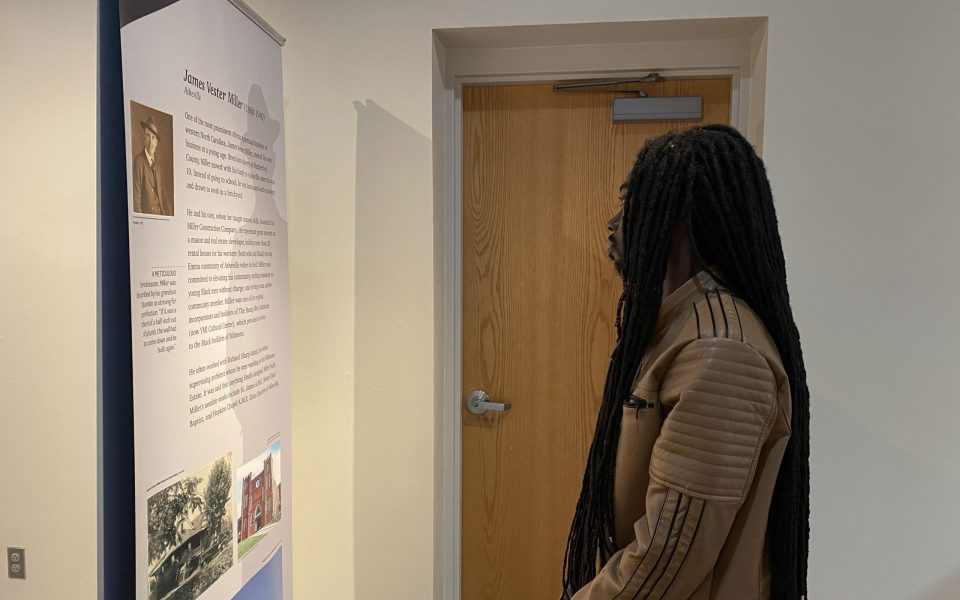

Featured photo: Delvon Peterson goes around the We Built This exhibit at NC&AT on Oct. 27.

If walls could talk.

That’s the idea behind We Built This: Profiles of Black Architects and Builders in North Carolina, a traveling exhibit on display in the University Galleries at North Carolina A&T State University until Dec. 9. The exhibit, made possible by Preservation Greensboro, highlights the stories of the Black architects who constructed or designed historical sites throughout North Carolina. It spans more than three centuries, providing historical context on topics like slavery and Reconstruction, segregation and more.

In a press release from A&T, associate professor and visual arts program director Roy Carter stresses the importance of knowing the history behind treasured landmarks.

“Many times, we walk into these facilities and admire them, and are not aware of those who built them,” Carter says.

Dudley Memorial Building, located in the historic district of campus, is hard to miss with its grand entrance adorned with intricate stonework, splayed arches and six tall, wide columns. Through the main entrance, immediately on the right is H.C. Taylor Gallery, where the exhibit “We Built This” lives.

Delvon Peterson took into the exhibit on Oct. 27 after leaving work. He’s interested in Black history and seizes any opportunity to learn more about it.

“We’re quick to go look at art from European artists when we can literally go and look at a piece of our [Black] history by simply going,” he says.

He continues, “As soon as you walk in, you feel the energy and significance of being there.”

More than a dozen near 7-foot scrolls in chronological order stand in neat rows neatly arranged around the sides of the room, one behind the other. On both sides of the scrolls is a brief biography of a builder, a portrait of them and images of buildings they constructed. Resting against the back wall of the gallery are two large standing boards, one covering historically Black colleges and universities, and the other Black churches. In the center of the room are two more large boards of the same style, but these are double-sided, designed to be read with the side of the exhibit the board faces. For the best viewing experience, visitors should start on the left side of the gallery, make their way towards the back and come back up on the right.

The exhibit highlights the accomplishments of those who constructed buildings that viewers may have visited themselves. From 1859-61, Elvin Artis served as a contractor for the construction of the John D. Bellamy Mansion in Wilmington. On the back of a decorative plaster piece on the rearback of the mansion are the initials of William B. Gould, an enslaved plasterer also featured in the exhibit. George Henry Black, from Winston-Salem, mastered the art of making bricks by hand by the late 1920s. His handmade bricks became a hot commodity, easing the reconstruction and restoration of structures and sidewalks around Old Salem. Salem Tavern, located in the Old Salem district, was built with bricks created by Black. He lived in the George Black House and Brickyard, located in Winston-Salem from 1934 until his death in 1980. The building is still standing.

As he walked around the exhibit, Peterson noticed the lack of women featured on the scrolls, but they were mentioned as mothers and wives. He hypothesizes this was due to sexist societal practices limiting job opportunities for women through the 18th to 20th centuries.

“That line of work would’ve been considered ‘man’s work’ for a long time,” he says.

That’s not to say women and children weren’t around.

“Even though they weren’t showcased, there were probably instances of Black women and kids helping,” he guesses.

To Peterson, the most interesting of the artisans was Julian Frances Abele, chief designer for all West Campus buildings at Duke University and the Duke Chapel. He died in 1950, 11 years before the first Black student would be enrolled at Duke.

“It’s interesting to think that we were good enough to design but not good enough to attend,” he says.

He notes how the exhibit brings a sense of home instead of feeling out of place, especially when viewing the boards dedicated to HBCUs and Black churches. Peterson grew up in a Black church, and although he doesn’t attend anymore, he’s gained a new appreciation for them.

“They weren’t built and given to us; they were built by us and for us,” he says.

He encourages those who can attend the exhibit to do so. Not only does it feature the historical relevance of some of the state’s buildings and their creators, but it also represents the resilience of the Black people who created them. These artisans, some the children of enslaved people, some enslaved themselves, failed to let their circumstances deter them from greatness.

“For me, it shows a good representation of us because no matter how many times we’ve been knocked down, no matter how many times we’ve been brutalized, no matter how many times we’ve been victimized, we manage to stand up again,” Peterson says.

“The buildings are mirror images of the people that made them.”

The free exhibit is open to the public during normal University Galleries hours, Monday through Friday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Saturdays by appointment. For more information, visit ncat.edu/cahss/gallery.

There will be a free talk on Nov. 9 in the gallery from 6-8 p.m.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply