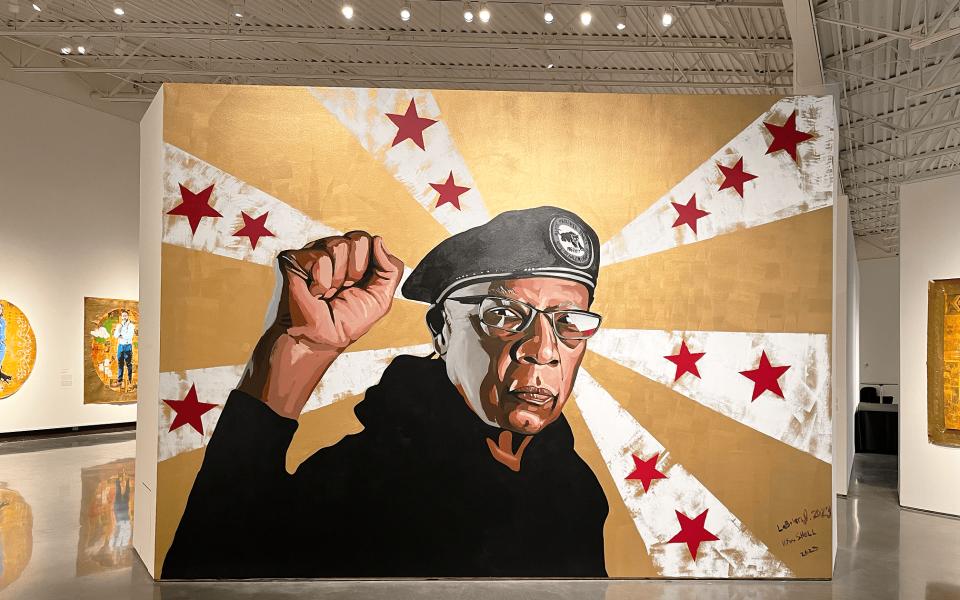

Featured photo: A mural of Larry Little is on display at SECCA until June 18 for the “Vitus Shell: ‘Bout It ‘Bout It, The Political Power of Just Being” exhibit (photo by Daniel White)

The adolescent girl stares out at the viewer as a camera flashes and captures the historical moment in progress. She stands out amongst the small group that has gathered, dressed in a bright yellow two-piece suit that hangs limply off her small frame. A monarch butterfly finds purchase on her left shoulder. The soft, black curls of her bangs kiss her forehead as she lightly places her left fingers over her right, just tight enough to grip the American flag that balances against her right shoulder. She doesn’t smile.

“A New Generation” by Stephen Towns was painted in 2021 but depicts a scene from just after the banning of segregation in the mid-1950s. The girl, unnamed, and two Black boys stand in the front row of the painting as five white men in suits position themselves behind them, and one Black man stands off center in the back row. The painting is one of the last presented to viewers in Stephen Towns: Declaration and Resistance currently on display at Reynolda House.

A mile away, another young woman dressed in yellow captures the attention of visitors. This time she’s wearing a sleeveless tank dress that’s bisected by a light blue shirt tied around her waist. Gone is the American flag and the butterfly, replaced by a pair of white doves that flank the girl in the background. Instead of meeting the viewers’ eyes this time, she looks off into the distance to her right but maintains a reserved posture, her right hand gripping her left wrist. Neither does she smile.

This girl, also unnamed, appears in the work “Do What You Do” as part of Vitus Shell: ‘Bout It ‘Bout It, The Political Power of Just Being at SECCA which opened just two weeks before the show at Reynolda.

The shows didn’t open in the same time frame for any reason except that maybe the curators wanted to have exhibits featuring Black artists for the month of February. And the artists’ styles diverge, with Towns opting to use large, traditional canvases and quilting while Shell prefers freeform canvases that hang off of grommets to create slightly curled edges. But then again, both artists hail from the South, and through their work, tackle issues of race, deeply rooted in their birthplaces. Shell, born in Monroe, LA, in 1978 predates Towns’ birth by just two years, the latter being born in Lincolnville, SC in 1980. And upon viewing the exhibitions in tandem, repeating motifs and a continued conversation about the story of survival, joy and the simple existence of Black people in America rises to the surface.

In Stephen Towns’ show, the artist follows a linear timeline of the struggles and triumphs of Black Americans starting from enslavement to the Black Codes during the post-Civil War era through Jim Crow and finally in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement.

Literature like the 1619 Project by Nikole Hannah-Jones and Caste by Isabel Wilkerson are displayed on a wall within the show. And in a world in which governors seek to ban African-American studies from schools and Black people continue to be victimized by the police state, Towns’ exhibit connects history to the recent present.

Images of men working on chain gangs in intricately sewn quilts give way to lush, painted portraits of notable individuals like Susie King Taylor, a nurse and educator who served in the Union military without pay. Painted in 2021, the work places Taylor in a verdant swamp as she stands amongst reeds that reach up to her waist. The sky behind her is painted in gold and like Byzantine saints of old, Towns sanctifies Taylor with a golden, studded halo. As with the girl from “A New Generation,” monarch butterflies converge on Taylor, acting as symbolic visualizations of hope. Other paintings depict nurses, crossing guards and coal miners who influenced American society in the next 100 years.

With the ending of Towns’ show after the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, viewers may be left wondering what happens to the individuals depicted in his paintings and their descendants for the next 60 years. And across the street in Vitus Shell’s exhibit, viewers may find their answer.

On the main wall as viewers enter the main gallery, Larry Little, dressed in all black, raises his right fist up in the air in a power salute. He wears glasses and his signature Black Panther hat atop his head as golden rays and white stripes with stars sprout from behind him.

The mural, which is temporary and unable to be saved because it was painted directly on the wall, highlights Winston-Salem’s most famous Black Panther. The work is Shell’s most recent piece in the exhibition and is part of the artist’s motivations to give Black people their flowers in life, rather than in death.

Not unlike the works of Kehinde Wiley, whom Shell himself notes as an influence, the artist’s pieces at SECCA depict ordinary people, often ones that make appearances in Shell’s life in Lafayette, LA.

Like Towns, who uses metallic paint and adornment to recalibrate Black figures as holy, so too does Shell in his depictions of members of his own community. In “Like It’s Hot,” Shell paints a beautiful young Black woman with long wavy hair in a cropped jean jacket and low rise jeans on top of muted advertisements peddling cigarettes, drugs and hair care. Behind her he adds a white, seven-pointed star and frames her with an oval, golden frame complete with flying cupids and a Baroque-like embellishment on the bottom. In one of the wall placards, Shell explains his approach to portraiture.

“I often ask people to be models for my work, and this does several things: It highlights the importance of people and encourages them to see themselves in a different light; it gives them a sense of importance and the possibility of seeing themselves in a different way,” Shell says. “There is a sense of freedom that can come from this.”

And indeed, part of the title of Shell’s exhibit, “The Political Power of Just Being,” further explains his motivations behind his work — his desire to separate the Black body from limiting narratives of pain and even defiance and survival, in the way that Towns’ exhibit does. As such, the two exhibits could read like opposites, with one telling the story of “Resistance” while the other argues for the mundane, the simple life for Black people.

But together, the shows work to tell a more complete and nuanced story of the Black-American experience — one in which the pained history of subjugation and survival in this country, to this day has deadly repercussions for many, which in turn, prompts the increasing need to create space for people to just be, to simply exist.

Stephen Towns: Declaration and Resistance is on display at the Reynolda House until May 14. Learn more at reynolda.org. Vitus Shell: ‘Bout It ‘Bout It, The Political Power of Just Being is on display at SECCA until June 18. Learn more at secca.org.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply