“‘I am waiting for my case to come up,’” Brian Lampkin reads.

He flips the page in Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s Coney Island of the Mind, leaning back in his seat. The amalgamation of barstools and armchairs makes the back of Scuppernong seem more like a living room than a bookstore as the Sunday afternoon moves on. A balding man reaches up to scratch his beard in thought as Lampkin makes his way through the poem.

Lampkin recites the piece as part of one of many celebrations across the world for the 100th birthday of Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Born March 24, 1919, Ferlinghetti made his mark through poetry, painting and co-founding City Lights Booksellers & Publishers in San Francisco, becoming a figure of the Beat Poetry movement. Events for Ferlinghetti spanned from New York City to Venice to City Light’s home in San Francisco. In Greensboro, a chalkboard sign reading “A Ferlinghetti Day” out front beckons fans of the anarchist Beat into Scuppernong Books, strangers relating through a counterculture of literature.

“‘I am anxiously waiting for the secret of eternal life to be discovered.’” Lampkin stops. “He may have found it, dear god.”

The room stays silent as Lampkin delivers the piece. Only the occasional creaky wooden floorboard breaks through the streams of consciousness the 1958 poem delivers. Lampkin says that of all of Ferlinghetti’s works, the full staff of City Lights Booksellers recommended this — a repetitive list of desires for the future called “I Am Waiting.”

“‘I am awaiting perpetually and forever a renaissance of wonder,’” Lampkin ends.

Ferlinghetti received an undergraduate degree from UNC Chapel-Hill in journalism, went on to earn a masters in English literature from Columbia and a doctorate from the University of Paris. Through his enterprise of City Lights, he helped publish figures from the wide-open or Beat poetry movements, including most notoriously Allen Ginsburg’s Howl and Other Poems.

The association landed Ferlinghetti with an arrest in 1956 for the sale of writing labeled as obscene. Ferlinghetti’s beating of the case led to a wider legal understanding of culturally relevant artistic works.

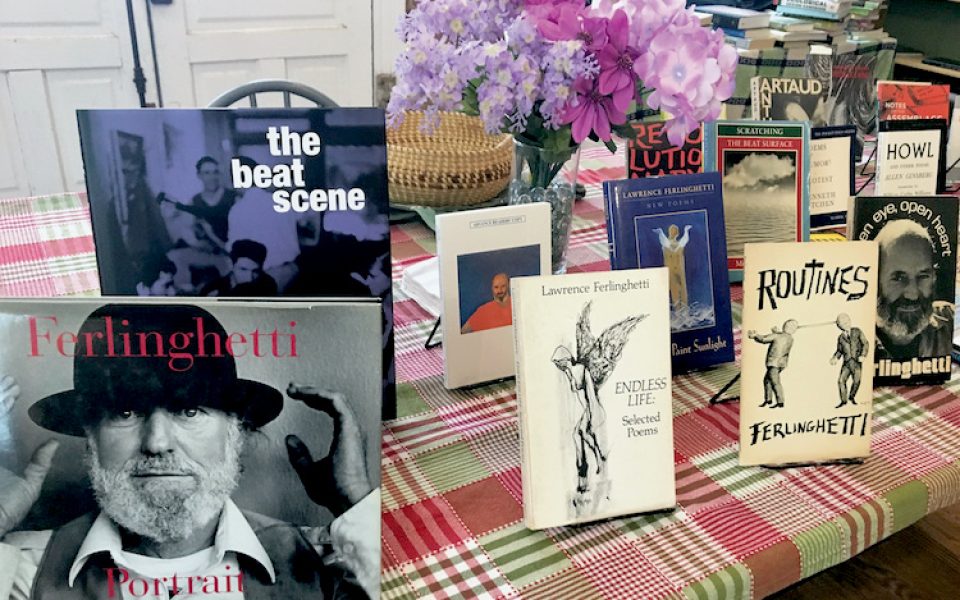

Lampkin grabs his copy of Ferlinghetti’s Little Boy from atop a plaid-covered table full of the man’s poetry, prose and criticism. His newest work came out on March 19 of this year, published on the cusp of a century of his life.

“I wanna publish a book at 100!” Lampkin laughs.

A college-aged man scoots his chair over to better watch as a projector turns on, displaying clips of Ferlinghetti walking around an art studio. On screen, he picks up a palette and then sets it down, turning to re-position vast stretched canvases of abstract and impressionist paintings instead.

“I met him once,” a man speaks up. He passes around an autographed copy of Ferlinghetti’s 1993 collection These are my Rivers bought from the famous bookstore.

A woman pauses, her hand on top of the loopy signature, as Lampkin breaks her attention briefly with his own story.

Lampkin’s encounter happened decades ago, at a party in the 1980s. The conversation was short, but impressionable.

“Of course I said hello,” he recounts.

The group continues on, bouncing around their discussion of Ferlinghetti and the Beat movement. They mention how some works fall into the white-male centrism of many literary canons, but the ripples made by movement remain.

“There is something about the energy of the works,” Lampkin says.

A young man mentions the rumors around psychedelics and drug use of the time, and a few who lived through the period laugh.

“There’s no doubt that the Beats allowed the ’60s to happen,” Lampkin continues.

Dave Williams nods, resting his elbows on his knees as he sits. He relives the memory of being a young boy in Lexington, North Carolina, finding solace in the writings of Ferlinghetti and his contemporaries like others in rural areas did. Peers took cross-country hitchhiking voyages inspired by Ferlinghetti contemporary Jack Kerouac and reflected upon their sense of humanity through Ginsburg.

“They found something in it,” Williams says. “Those kids did.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply