In 1946, three voters in Illinois

took a complaint to the Supreme Court: that the state had failed to redraw its

congressional district lines since 1901, resulting in rural districts that

lorded political power over their overpopulated urban counterparts. Writing for

the majority, Justice Felix Frankfurter averred in Colegrove v. Green that “courts ought not to enter this political

thicket.”

Sixteen years later, in 1962, the

high court overturned Colegrove with

a finding that established the court’s authority to referee redistricting and

established the “one person, one vote” standard for apportionment.

Ever since, the court has been

steadily inching towards intervention in partisan gerrymandering.

In 2004, the court ruled 5-4 against

Democratic voters from Pennsylvania claiming their rights had been trampled as

a result of partisan gerrymandering by the Republican legislature. But Justice

Anthony Kennedy, who cast the deciding vote in Vieth v. Jubelirer, only reluctantly joined the majority because he

couldn’t identify a suitable tool to measure partisan gerrymandering to

determine whether it was excessive.

Proponents of fair districting have

been searching for a workable standard ever since.

Last year, the Supreme Court came

tantalizingly close in considering Whitford

v. Gill, in which Democratic voters in Wisconsin claimed they were harmed

by redistricting maps drawn to advantage Republicans. The high court ruled that

the plaintiffs needed to prove individual harm specific to their own districts

and remanded the case back to the district court.

The high court will have another

crack at the question on March 26 when they hear arguments over North

Carolina’s partisan gerrymandering scheme, in Rucho v. Common Cause, in which the Republican legislative majority

in North Carolina is appealing a lower court ruling that deemed the 2016

congressional map to be an unconstitutional partisan gerrymander.

“To be sure, the General Assembly

was quite candid about its partisan objectives, but it had just been faulted by

a federal court for lacking a clear record of political, rather than racial

motivation,” lawyers for the Republican majority wrote in their brief last

month. “Those reassurances were correct, and the time has come for this court

to make clear that the Constitution does not provide courts with the tools or

the responsibility to say how much partisan motivation is too much.”

Rep. David Lewis, the Republican

lawmaker who led the redistricting effort for the state House, said at the

time: “I propose that we draw the maps to give a partisan advantage to 10

Republicans and three Democrats because I do not believe it’s possible to draw

a map with 11 Republicans and two Democrats.”

The voters challenging partisan

gerrymandering in North Carolina also recognize the potentially far-reaching

consequences of the high court’s ruling in this case.

“By the standards of the past, North

Carolina’s current congressional plan is exceptional,” lawyers for the League

of Women Voters of North Carolina wrote in a brief filed on Monday. “It is the

first map in American history to ratify the pursuit of maximal partisan

advantage and to have its architect boast, on the record, about his desire to

harm his political opponents. It is the single most pro-Republican

congressional map of the last half-century. And it has set this record even

though the state’s political geography mildly favors Democrats. If this court

holds that partisan-gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable, however, the 2016

plan will be the wave of the future. In the 2020 cycle and beyond, both parties

will emulate — or exceed — its abuses, openly entrenching themselves

in power using the full array of modern mapmaking technologies.”

Quite simply, the League and other

plaintiffs are proposing the same tool as their Wisconsin counterparts — a

measure known as the “efficiency gap” — to determine whether partisan

gerrymandering has gone too far.

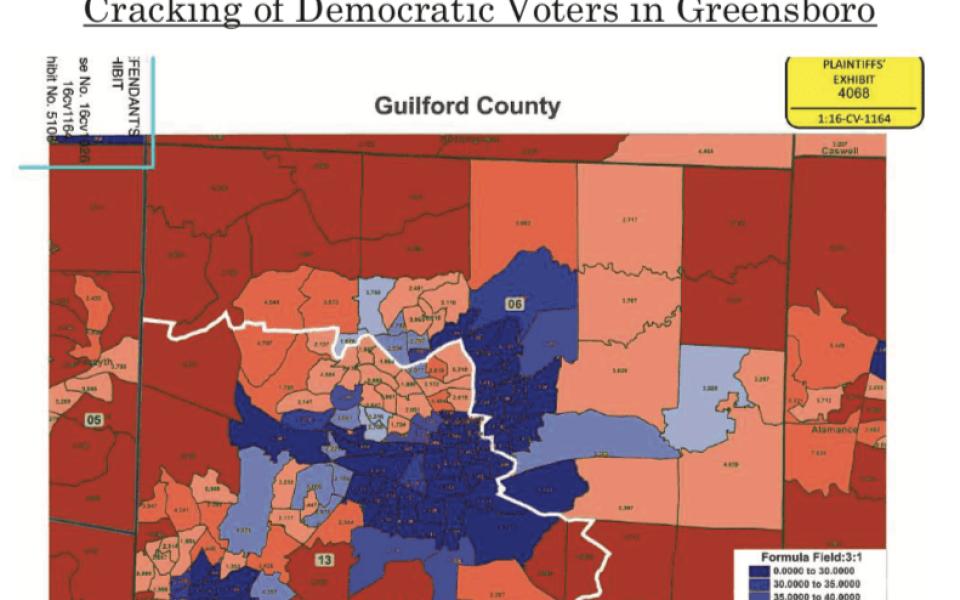

The Republicans entrenched their

legislative advantage in North Carolina by “cracking” Democrat voting blocs in

Greensboro and Fayetteville, and “packing” them in Charlotte and Raleigh. The

sizable Democrat vote in Greensboro is entirely wasted by being split between

the Republican-leaning 6th and 13th districts, whose

shared boundary runs right through the middle of the NC A&T University

campus. By contrast, a far smaller number of Republican votes are wasted in the

three districts where Democrat constituencies are packed.

The efficiency gap, then, is the

difference between wasted Democrat votes and wasted Republican votes. An expert

witness for the League will testify that North Carolina holds an efficiency gap

of 27 percent favoring Republicans, meaning that in a hypothetically tied

election, Republicans would win 77 percent of the state’s congressional seats.

Predictably, even in 2018 — a wave Democrat election — Republican candidates

prevailed in 10 out of 13 congressional races — with an asterisk on the 9th

Congressional District, where the state Board of Elections ordered a new

election after finding coordinated election fraud.

It’s not just Republicans imposing

victor’s justice over Democrats. In states like Maryland the sword is in the

other hand. If the Supreme Court gives a green light to North Carolina’s

extreme gerrymandering, Democrats will join Republicans in the grift — to the

detriment of all voters.

“Both parties are poised to wield

unified control of many state governments after the 2020 election,” the

plaintiffs warn. “If given a judicial green light, both parties will exploit

their authority to gerrymander even more aggressively, using even more potent

techniques than they have to date. Like North Carolina’s mapmakers, they will

ruthlessly crack and pack the opposing party’s voters. They will also program

computer algorithms to maximize their partisan advantage and make adjustments

throughout the decade to any districts that seem to be slipping from their

grasp. Through such machinations, ‘those who govern,’ who ‘should be the last people to help decide who should govern,’ will try to extinguish

‘the political responsiveness at the heart of the democratic process.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply