“Even as a little girl, I can remember that we didn’t need to be on the highways at night,” says JoAnn Stevens of Snow Hill.

Her voice, along with those of a few other elder black North Carolinians’, resounded through the Greensboro History Museum’s auditorium speakers on Jan. 9 as dozens learned about the North Carolina Green Book Project.

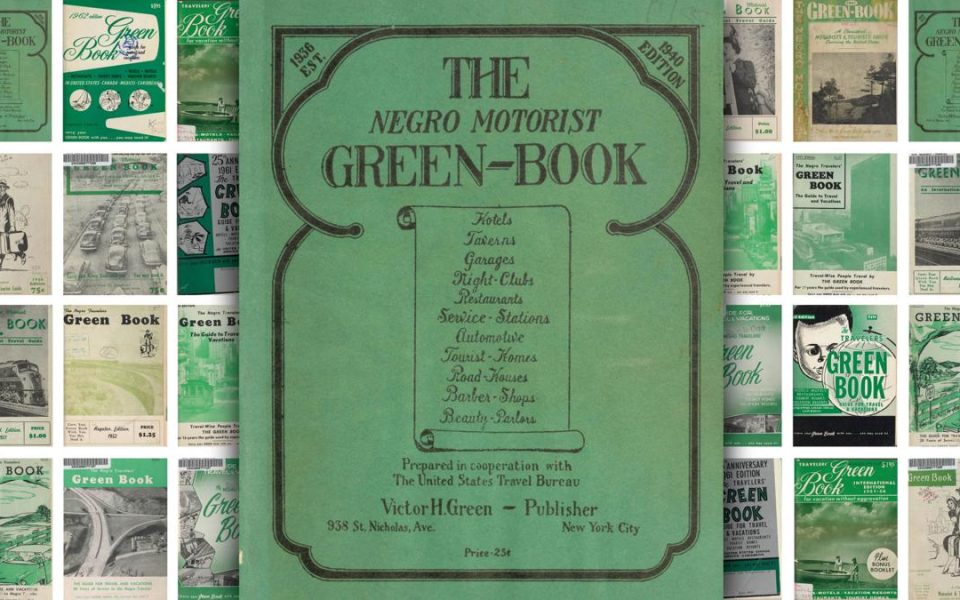

Angela Thorpe, acting director of North Carolina’s African American Heritage Commission, detailed the statewide effort to document community stories in connection to the 327 North Carolina historic sites listed in The Negro Motorist Green Book during its publication from 1936 to 1966. From hair salons and diners to motels and nightclubs, the sites listed in the annual catalog chartered safe course through the constraints of formal segregation. The project — which situates memory as artifact and recognizes sidelined communities as loci of knowledge — will culminate in an interactive web portal, two identical traveling exhibits and related community programming in March 2020.

“We wanted to understand what it was like for African-American families, businesspeople and individuals to travel in North Carolina in the Jim Crow era,” Thorpe says, noting that black people continue to document discrimination while traveling with hashtags like #TravelingWhileBlack and #AirbnbWhileBlack.

“There are still things African-Americans in this state and across the world, really, are still experiencing as it relates to segregation and discrimination as we try to move our bodies around the world. We hope some of the programs we can do will explore that reality.”

Cassandra Williams, education coordinator at the International Civil Rights Center & Museum in downtown Greensboro, spoke to the packed auditorium about her own connections with the publication.

“Imagine my surprise one day as I was giving a tour to a group of visitors and I was looking at the pages from the Green Book — which is a part of our exhibit in our Travel and Accommodations Gallery — and my eyes fell upon Traveler’s Inn in Bloomfield, West Virginia,” Williams says. “I explained that’s my Great Uncle Charlie’s hotel where my mother her sisters and brothers used to visit in the summer, listed right there in the Green Book.”

-

1960 edition of the Green Book -

1956 edition

While all 18 sites listed in Forsyth County have been demolished, five of the 17 sites in Guilford Country remain, one of which is the Magnolia House on Gorrell Street, which Williams remembers from her childhood in Greensboro.

“I passed by regularly, walking to Girl Scouts meetings or downtown back in the days when transportation was either your feet or the city bus,” she says.

Williams’ recollection is exactly the type of memory research historian Lisa Withers wishes to hear from fellow North Carolinians.

“To my knowledge, what makes our project unique is its attempt to connect the human stories,” Withers says. “Projects in other states are more on the historic preservation side of our field, identifying whether these buildings are still standing or not. We’re adding the human element.”

“You all see how tiny it is, how small it is, how flimsy it is?” Thorpe says, showing the audience a copy from the stage. “But inside of it, it was filled with so much. If you open up that Green Book, you know what you’ll find? Oasis. Oasis spaces. A tagline that often appeared in and on the Green Book was: ‘Carry your Green Book with you. You may need it.’ And there was a reason for that; in the era of legal segregation, protecting your body and your humanity as an African-American in this country was critical and that teeny little book had the ability to do that. When you opened that book, you were able to find spaces that could provide you refuge, protection, comfort as you traveled through the United States.”

Withers invites the public to connect her with locals who may be able to offer contacts, stories, pictures and other memorabilia from their own experiences with these cultural institutions.

“It’s so important that we’re able to connect with community members… so we won’t forget not only the businesses and the roles they played in making our cities and even rural areas safe to travel in, but also that… people built lives on these businesses — the Green Book also documents livelihoods,” Withers says.

According to her, many African-American-owned businesses were demolished during “urban renewal” periods such as the development of Highway 147 in Durham or Highway 52 in Winston-Salem.

At the end of the evening, an audience member asks Withers what she sees as the biggest challenge of this project.

“My belief is that the biggest history books are in the graveyard,” he says.

In a way, she says, he’s alluded to the problem, exacerbated by the passage of time.

“Unfortunately, due to the nature of our society during the time when a lot of archiving was happening… we really do have to connect with community members to help fill in those gaps,” Withers says.

Research intern Bria Johnson — a graduate student earning her master’s in history at NC Central University — is doing that work, partly with recording equipment in the homes of elders like JoAnn Stevens. According to Thorpe, it’s no coincidence that Johnson, like each intern affiliated with the NC Green Book Project, studies at an HBCU.

“A major project goal is building and developing the next generation of African-American heritage practitioners, the next generation of people who will be doing this work.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply