A poster of a muscly man in a black leather cap and jockstrap hangs on the wall while magazines featuring leather-clad dominatrices clutter a table.

The mementos are part of Leather History Preservation Weekend, an event by the Leather History Preservation Foundation that brings the leather community together to share stories. The event, which is in its second year, drew visitors from across the country — as far as Alaska — and was held at the Red Lion Hotel in High Point on November 2-4. Panels of historians, play rooms, a library, vendors and a bootblack area (kind of like a shoeshine but for all things leather) made up the event.

None of the sources cited in this story speak for the association.

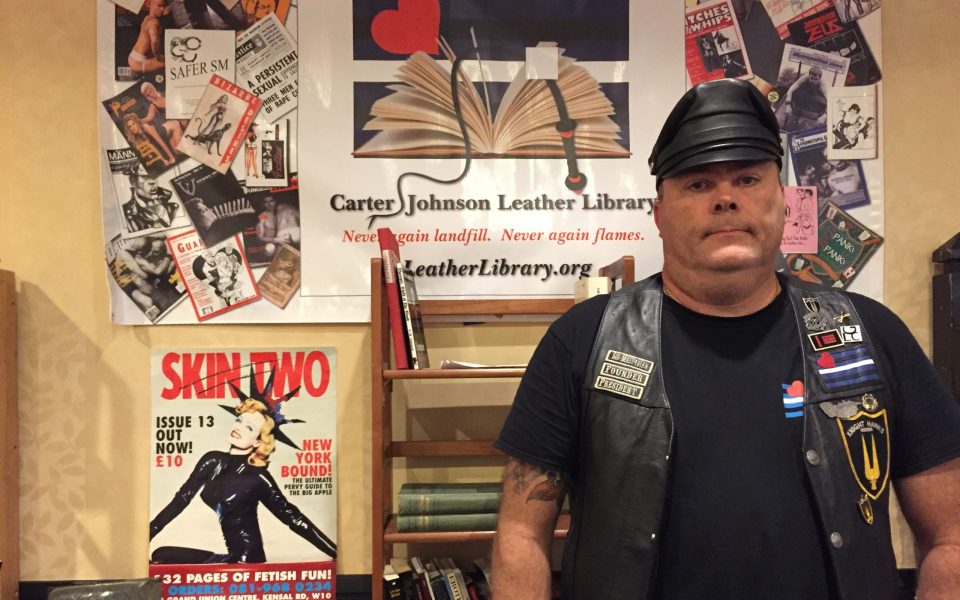

Sir Michael Malcavian brought these items to the conference. Malcavian is not his real name; like most people in this story, he preferred to be identified by his scene name. The objects are part of an annex of the Carter Johnson Leather Library which is dedicated to preserving leather mementos. His is one of 11 annexes the library has. He points to a large, wooden chair in the corner, one he refuses to sit in.

The throne, which is made of solid plywood and painted black, towers almost as tall as Malcavian himself as he stands next to it, dressed in a black shirt, jeans, black leather cap, leather vest and black boots.

“It belonged to Master Doug Harris at the Sanctuary of a Dark Angel,” Malcavian says. “He sat in it. I don’t sit it in out of respect.”

The Sanctuary of a Dark Angel, which closed in 2003, was a semi-public BDSM dungeon in Atlanta operated by Harris, a gay man, and his family, and was one of the largest in the Southeast. It was a place to explore one’s sexual fantasies and a haven for those in the leather community.

Now, the Leather History Preservation Foundation hopes to create that same sort of welcoming atmosphere while preserving decades of leather history. The foundation, which is based out of Georgia, puts on the annual event in North Carolina each year, recording oral histories of attendees and collecting and displaying artifacts from the leather community.

It’s widely thought that the leather subculture grew out of post-World War II biker culture, which thrived when soldiers came home and joined gangs for a sense of community as well as danger. When the 1953 film The Wild One starring Marlon Brando further aligned the hypermasculine, “bad boy” persona with leather attire, it presented gay men with a different form of expression than the mainstream stereotypes of the time. At the conference however, men and women and genderfluid attendees of all different sexual orientations came clad in leather to commune.

Lily Mia Lilith (also not her real name) joined the community in 2012 when she was in her mid-twenties.

“I had been sexually abused growing up,” she says. “I spent my whole life feeling alone or like I didn’t belong.”

Lilith, who identifies as genderfluid, was introduced to leather culture by her mom, Tori Jones (also not her real name), the executive director of the foundation.

“People didn’t care how screwed up I was,” she says. “They just accepted me.”

Jones’ husband, Geoff Wingard, is the treasurer and webmaster of the foundation. Although straight, he says he also discovered a home within the leather community decades ago.

“I connected with a group on Yahoo chat called ‘Bondage A Gogo,’” he says. “And I found that these people were doing the stuff I fantasized about for real.”

Wingard, who uses his real name, says that many in the community still aren’t “out” for fear of discrimination.

“Americans are so damn uptight about sex it’s not funny,” he says. “There are some people who are out as gay, lesbian and trans but aren’t out as part of leather. For a lot of people it’s riskier.”

Back in the room with the artifacts, Vi Johnson, the founder of the Carter Johnson Leather Library, sits surrounded by people she calls family. She’s been involved in leather for over 40 years and is “Mama” and “Grandma” to many in the community.

The words “Never again landfill” and “Never again flames” are printed on the poster above her. They symbolize why she started the library 25 years ago.

Johnson had been mentoring “young kinklings,” as she calls them, and was collecting educational materials online when a realization changed her life.

She remembers winning a book on Ebay but later found out that the man she was bidding against had been buying books just to burn them.

“I thought, ‘You don’t get to destroy my family’s history,’” she says. “I started telling more stories about who we were and where we came from. To help us understand that our sexuality is normal. It’s just another way to love.”

She says that sometimes when leather members pass away, their mementos are thrown away or burned by family members out of shame. The library, and the foundation, is a way to combat that.

“The next generation needs to know where we come from,” she says.

Outside the room, Tim Smith, an attendee, wears a shirt that reads, “I am the penis whisperer” along with a black leather vest with yellow stripes and a neatly trimmed goatee. Smith says as a gay man growing up in rural North Carolina, finding the leather community meant finding a family.

“It’s like a family reunion,” he says. “Our last name is ‘leather.’”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

[…] Article on the history of the Carter/Johnson Memorial Library […]