As an Asian child, I was always told to remove my shoes when entering a household; I still do. It was only when I began visiting my white friends’ homes in elementary and middle school that I realized that this wasn’t necessarily the norm for every family.

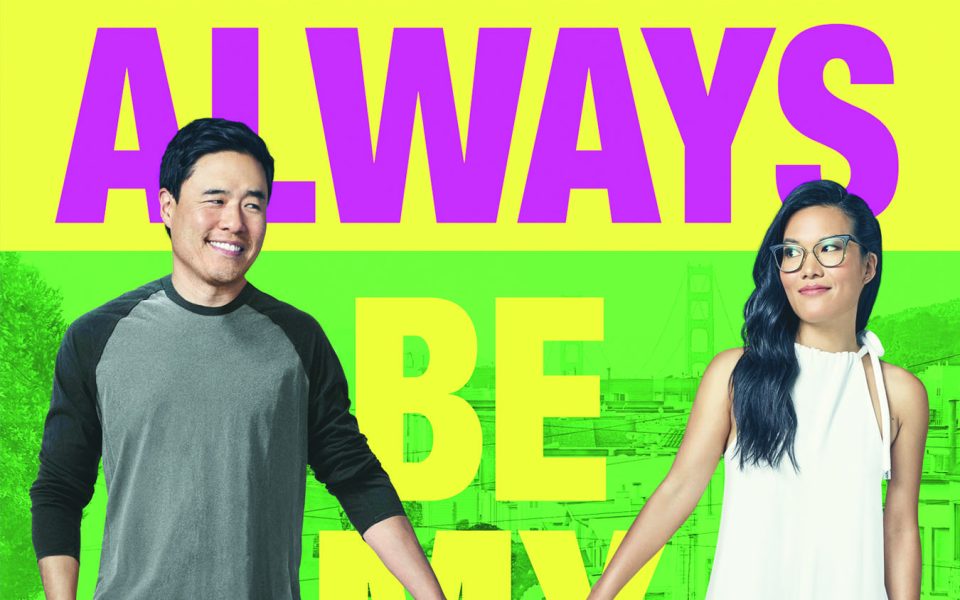

In a scene from the recently released Netflix movie Always Be My Maybe, director Nahnatchka Khan (creator of “Fresh Off the Boat”) purposefully crafts a shot where two young Asian girls run through a house during a birthday party, but only after removing their shoes prior to entering and then carrying them through the house so they can slip them back on once on the back patio. The film, which debuted last Wednesday is notable because, like Crazy Rich Asians from last year, it features an almost all-Asian cast with stand-up comedian Ali Wong and “Fresh Off the Boat” star Randall Park as its leads. The film plays like a traditional rom-com by following Wong and Park from their childhood as best friends into adulthood when they reconnect.

At a passing glance, the film seems like just another fun but relatable romantic comedy. However, like Shirley Li of the Atlantic pointed out in her article on June 2, Always Be My Maybe is significant in so many ways because of the deliberate choices made by the cast and crew in how the story is told.

For example, to those with no connection to Asian culture, the scene with the girls might very well be overshadowed by all of the other notable scenes in the film. I mean, it only lasts a few seconds. But to those who know, the shot is a call back to our own childhoods, to our own cultures.

“I spent more time on that shot than I think a director would have if that wasn’t an important detail,” says Khan in the Atlantic piece. “We had to get that timing right. You could get into [that scene] in any number of ways, but I liked showing that.… It’s a part of this world.”

In so many other little ways, Always Be My Maybe — which is written by three Asian writers including Park and Wong — makes important efforts to subtly ground the characters in their respective Asian cultures and identities without pigeonholing them.

As kids, Wong and Park can be seen riding a trolley (the film is set in San Francisco) while eating Pocky, or wrapping dumplings with Park’s mom.

And yet, they are also still just normal kids. They dress up as Wayne and Garth from Wayne’s World for Halloween and they play music in a band. The parents don’t have thick accents. They don’t have to be good at math or play the violin or do karate.

They look, think, and feel like us.

Of course, being Asian is an individual and varied experience; we’re not all the same.

But the particular ways in which Wong, Park and Khan imbued their lived Asian-American experiences without having to smash the audience over the head is refreshing and a welcome departure from the decades of racist, stereotypical portrayals of Asians that we’ve gotten. And that’s if we’re depicted at all.

With the increased awareness of the importance of diversity and representation in media, I look forward to seeing more characters that look like me living complicated, regular lives whether it’s in a romance or drama or horror.

It’s about damn time.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply