“Dee-ee-eep river, my home is over Jordan/ Dee-ee-eep river, Lord I’m going over into camp ground/ Oh, don’t you wanna go to that milk-and-honey land where all God’s children are free? Dee-ee-eep river, my home is over Jordan.”

James Shields, director of community learning at Guilford College, sang this spiritual yards from a 350-year-old tulip poplar, a historical destination within the New Garden woods, which is listed on National Parks Service’s “Trail to Freedom” map.

“We know this tree was a witness to some of the things Levi [Coffin] talks about, and he talks about as a young boy going to these woods, taking his sack of corn under the pretext of feeding the hogs. He had bacon, sometimes clothing, but most importantly he had information and he had empathy. He would sit and he would listen to their stories, to the songs that they would sing. He would listen to just how hard and cruel slavery was to the point where it continued to encourage him to do his work.”

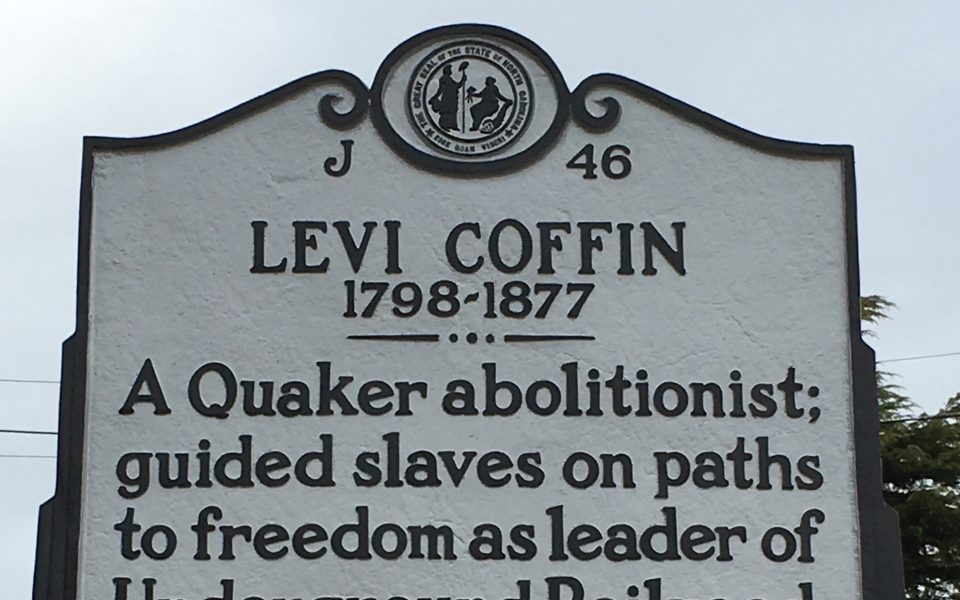

The North Carolina Fellowship of Friends and the North Carolina Friends Historical Society hosted a standing-room-only event on Feb. 9 at the New Garden Friends Meeting across from Guilford College’s campus. The occasion recognized the bicentennial year of the first known Underground Railroad activity in Guilford County: Levi’s cousin Vestal interceded on behalf of a free black man John Dimery, offering directions to a safe haven in Richmond, Indiana as the sons of Dimrey’s former owner attempted to re-enslave him. Levi, born in the New Garden Quaker society in 1798, is himself a significant figure in the history of Guilford County’s role in the Underground Railroad, and his pursuits illustrate the unique role of children in the loose social networks that supported enslaved people’s journeys to freedom. According to research at Guilford College’s Hege Library, the Coffins helped more than 2,000 slaves escape to freedom.

“It’s said that the song ‘Deep River’ is about our Deep River and I would like to think that it is,” Shields said. “We talk about the ingenuity of the freedom seekers, we know the spirituals were critical, not just as a form of uplift but as code for instruction, to tell you where to go. And they’re an example of how my ancestors were able to take their oppressor’s religion and make it their own.”

The Quakers that migrated to the Deep River and New Garden areas in 1771 were fiercely abolitionist, but not homogenous and not without their own rules of engagement.

“Quakers had integrity, and part of having integrity was following the law — and remember: Slavery was the law in North Carolina,” he said. “So, the idea that you would go and take someone’s property, there was no integrity in that, but if someone came to you or if you saw that someone had been kidnapped, that’s a different matter.”

One of the primary routes went through Greensboro up to Fancy Gap in southwest Virginia and then into Kentucky and across the Ohio River to freedom, though some escapees decided to stay in the mountains or venture further west. Shields and Guilford College history professor Adrienne Israel spoke of false-bottom wagons, and other tools “conductors” would use to usher people towards freedom in daylight, though most travel happened at night, to the slavecatchers’ disadvantage.

Both speakers stressed that the Underground Railroad was an interracial movement, though not without nuance.

“Whether the Quakers were there to help or not, there still would’ve been an Underground Railroad because the impetus for change has to come from the oppressed people themselves,” Israel said. “That partnership won’t work unless there is a sense of balance. Our understanding of this subject won’t work unless we acknowledge it wasn’t just a few individual free blacks but the free black communities as a whole supported these efforts. Even enslaved people who themselves did not try to run away were helping others.”

“A lot of times, we get caught up in the Quakers doing their work and as much as we appreciate it, African Americans played a major role in gaining their freedom as well,” Shields said, alluding to a pitfall of stripping agency from enslaved Africans in historical analysis.

“They came here with skill,” he said. “When you think, for example, of the enslaved Africans of the sea islands of South Carolina, they were sent there because they knew how to grow rice; they knew how to take a saltwater marsh and turn it into a freshwater marsh and grow rice. That’s engineering.”

Though plantation culture thrived along the eastern coast, some Quakers did own slaves and there was a time when the New Garden Meeting formally condemned the Underground Railroad.

“Among these white allies, of course, were some of the Society of Friends,” Israel said. “But the truth be told, here in North Carolina there were many Friends who were slave owners and not like the Mendenhalls who were doing it to prepare them for freedom, but for the money. All of them who participated [in the Railroad] did so because of their inner sense of what was right, not because they were supported by their Meeting,” she said.

They risked fines, jailing, loss of property and ostracization.

Yards from the great tulip poplar tree on Saturday afternoon, Shields questioned his listeners before concluding the hike with “Deep River.”

“The reality is we got a lot going on in our country right now… and a lot of it is unnecessary,” Shields said. “This is why continuing to tell this story is so important. We can come together, we can do the right thing for people that are seeking refuge. We have a lot of folks in our county as we speak who are fearful of the knock on the door. What are we gonna do? What are you willing to risk? How far are you willing to go? Are you willing to go up against family and friends?”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply