It’s a Tuesday night, and so Matty Sheets, like he has done almost without exception for the last 17 years, drags himself out to host open-mic night.

The clubs have changed — first it was the Flatiron with his pal Mikey Roohan; later it moved to New York Pizza before it landed here, at the Westerwood Tavern, where he’s held this Greensboro standard for the last 110 weeks, missing just one installation for a trip back home to New Hampshire to celebrate his mother’s 70th birthday.

“On my brother’s frequent-flyer miles!” he exclaims. “First class!”

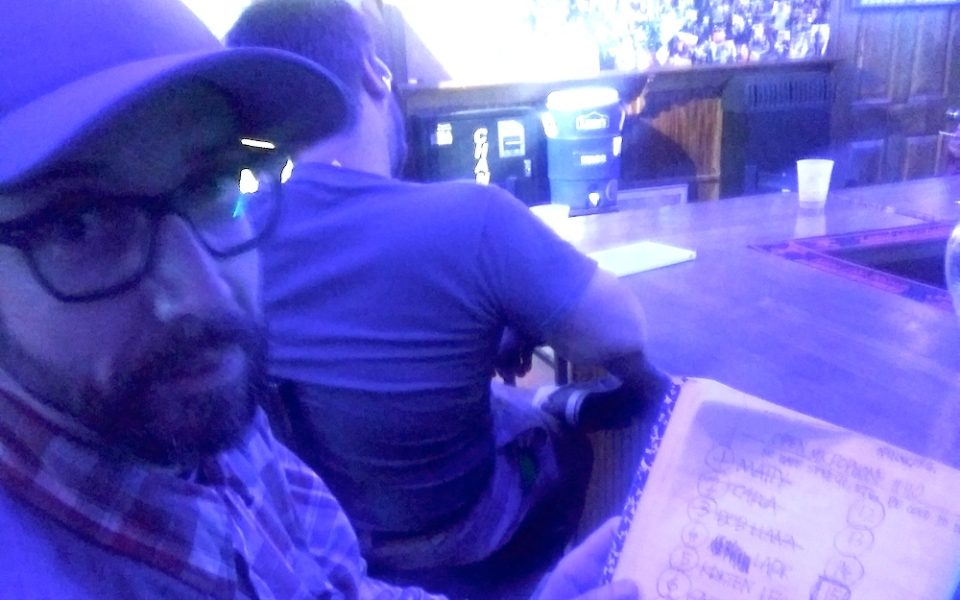

It’s half an hour before showtime and he’s working the floor, double-checking the sign-up sheet against people who are actually in the room. He keeps the list in an old-school marbled composition book, crosses off each act as they get on stage.

It’s a different show every week. Tonight a few first-timers will make their debut, including a groovy folk singer from Atlanta named Carly who will pull a couple sets. After he tunes his guitar at the bar, Michael Springer will drop a couple of tight originals to the barroom’s delight.

“He just moved to Greensboro,” Sheets will say. “He’s been here since Saturday.”

Then there’s Bob Liana, a harp player who’s in town on business from New Jersey who likes to drop in on open-mic nights when he’s on the road. Before he begins his piece, he’ll admit that back in the 1970s he studied under Piedmont blues harmonicist Sonny Terry, and then rip into a frenzy of blowing, stomping, hooting and hollering to raise the ghosts of the flatlands.

Sheets has been a stanchion of the city’s creative underclass for 20 years. He’s played with Laila Nur and Molly McGinn. He’s played with Magpie Thief. He was a Monkeywhaler and a Blockhead. And does anyone even remember Deviled Eggs?

And hey — there’s Kristen Leigh over in the corner of the Westerwood Tavern, waiting for the show to begin. She called herself Callie West when she used to play Sheets’ Flatiron open-mic night, and eventually joined his band. Later she’ll pull out a shruti box and make it drone like a bagpipe while belting out a country spiritual and, on guitar, an original.

Sheets hasn’t seen her in 10 years, but he loved her once, long ago.

But maybe he loves them all.

He wants you to know about Brandi Alexandria, who just moved up from Charlotte and has been coming by to sing a capella for a couple weeks now. He wants you to know about Mikey the bartender, about Buster the dog, And there’s this new act, Film Noir, featuring a young, scorching guitarist dripping with jewelry and a bearded grad student making rhymes. Later on, they’ll enter quickly through the back door, burn the place down with a short set and then make a hasty exit.

“Oh yeah,” Sheets says now. “Those guys.” They’ve already landed a Thursday night gig at Preyer Brewing, he says.

He’s about to go on, so he finalizes the list in the notebook. At the Flatiron he used a chalkboard on the wall, and at New York Pizza he wrote it on a pizza box, until he felt guilty for wasting a whole pizza box, so he started stealing the white sheets of paper from the folded boxes and using that. He started using the notebook after he settled in here at Westerwood.

He’s still got the flannel shirt, the ballcap, the thick glasses that make him look like he’s staring at everything with wonder, but Sheets has gained a kind of troubadour’s gravitas after all these years holding it down, through sickness and health and everything else that came with it. He’s wiser. And maybe a little tired. But it’s showtime.

Matty Sheets shuffles to the stage with a ukulele strapped across his body with what looks to be a piece of red ribbon tied around the instument’s waist. In a moment he’ll drop a four-stringed lament that somehow beautifies his pain and gives it to the room like a gift. But before he can open his mouth to the microphone, the crowd comes alive with shouts and whoops.

“Thank you for being Matty Sheets, you beautiful son of a bitch!” a bar patron shouts.

Sheets nods his head. It’s all he ever wanted.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply