This story was originally published by NC Policy Watch. Story by Joe Killian.

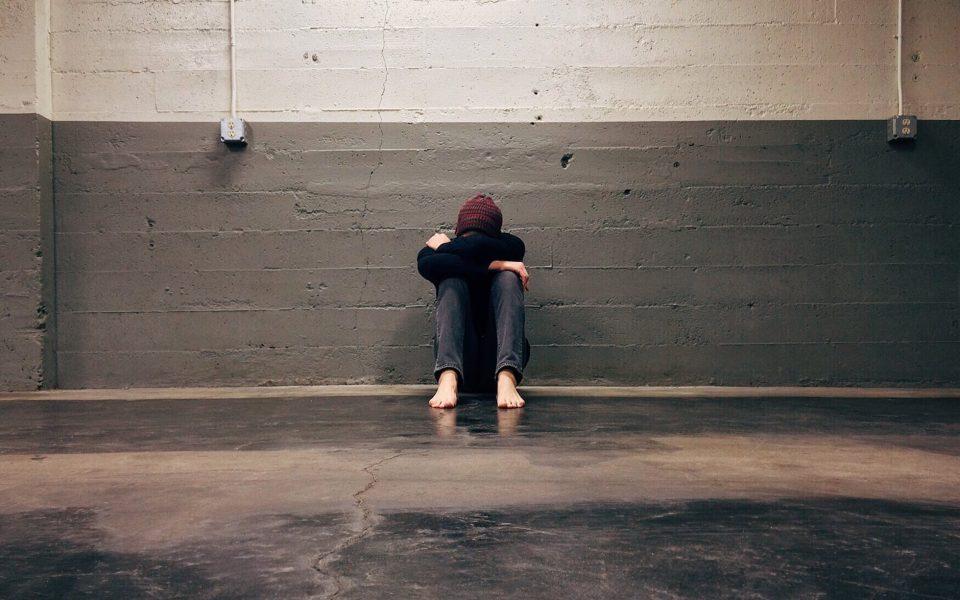

Marcella Middleton grew up in foster care in Colorado and North Carolina and was taken to therapists and put on medications at a young age.

“A lot of people who really weren’t experienced were trying to diagnose me,” she told a town hall on the youth mental health crisis in Winston-Salem last week.

A good therapist helped her sort through the trauma of her early childhood and the experience of living with strangers, adjusting to foster homes. Now an adult volunteer with youth advocacy group SAYSO and the Pembroke County Housing Authority, she’s trying to help a new generation of young people navigate caring for their mental health.

“When I think about the young people now who are in similar situations as I was, they have a different journey,” she said. “The Internet is making us all feel bad about ourselves. They have to contend with that on top of so many other things in their personal lives.”

That’s why recent political agreement on new and expanded funding for mental health care in North Carolina is so important, Middleton said. The staggering number of young people now facing mental health challenges is a bad omen for the future, she said.

“When you’re younger, people are kind of understanding,” Middleton said. “But if those things — if your mental health — is not supported for you, how are you supposed to be successful as an adult?”

Thursday evening’s town hall was the eighth in a series held by the state Department of Health and Human Services and state Senators Joyce Krawiec (R-Forsyth), Jim Burgin (R-Harnett) and Paul Lowe (D-Forsyth).

The lawmakers and NCDHHS Secretary Kodey Kinsley acknowledged that decades of underfunding and stigma surround mental health treatment. And those factors converged with the COVID-19 pandemic to create an unprecedented disaster.

The most recent data from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show the toll the COVID-19 pandemic has had on American mental health in general – but for youth, there has been a particularly steep decline.

- In 2021, more than 4 in 10 (42 percent) students felt persistently sad or hopeless and nearly one-third (29 percent) experienced poor mental health.

- In 2021, more than 1 in 5 (22 percent) students seriously considered attempting suicide and 1 in 10 (10 percent) attempted suicide.

Negative outcomes among LGBTQ youth are particularly pronounced, according to the CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data & Trends Report.

On Thursday, the panel of state DHHS officials and lawmakers heard the frustration and anguish of those who have been left to navigate a hollowed-out mental health support system in the state.

This situation, however, is finally on the verge of changing, Kinsley said.

Last month, after nearly a decade of resistance by Republicans in Raleigh, state lawmakers announced they had reached an agreement on expanding Medicaid in North Carolina. Earlier this month, Gov. Roy Cooper announced a plan to invest $1 billion in mental health services, a number both Democrats and Republicans agree is necessary.

“We need to take the signing bonus from expansion and invest it thoughtfully over time to really change a system that has been antiquated,” Kinsley said.

Lawmakers — Democratic and Republican — agreed. They also emphasized the need for communities to come together to support those with mental health needs and their families as state government scrambles to catch up.

“As a believer, I follow what the Bible says,” Burgin said. “It says if you go on a journey, go with someone so that if you stumble, there’s somebody there to hold you up. I think that’s what peers do.”

People like Middleton and the groups with whom she works have been essential stopgaps in this crisis, he said.

“Having someone who has been through it, who can tell you what to expect,” he said.

Government representatives hear from a lot of people and families with mental health problems and few resources these days, Krawiec said.

“And we’re the last resort,” she sad. “You can be sure they’ve talked to a lot of folks before they come to us. It’s heart breaking. It breaks your heart.”

Properly funding and reimagining mental health care in the state is critical, she said.

“We realize it, and we’re going to do all that we can do,” she said.

Lawmakers have been going back and forth on Medicaid expansion, Lowe said — a long journey that finally seems at an end this legislative session.

“I think the citizens of North Carolina, without a doubt, will be helped by the expansion of Medicaid,” Lowe said.

But traveling the state and hearing the stories of people suffering in the current system, he added, has made it clear the problem was left to compound too long.

“It’s beyond anything that most of us could have imagined,” Lowe said.

The current crisis has focused people, Kinsley said, and perhaps led to opposing political sides coming together to address it. But the problem was there before COVID-19, which pushed the current system to the breaking point and has been particularly devastating for young people.

“Over the last two and a half years we’ve seen first-hand isolation and stress and trauma that has touched every single person in this state, grief and loss that has touched every single person in this state,” Kinsey said.

“And that bears out in the data,” Kinsley said. “We see increasing rates of anxiety and loneliness, disproportionate among our younger people, people who don’t have the same resiliency and framework as older folks may have. And at a time when we had unprecedented fear and frustration in the midst of the pandemic, everybody was confused. We see this now bearing out with 350 people sleeping in emergency rooms without a place to go, people sleeping in DSS offices without access to treatment.”

The state needs to pay for “upstream” care to prevent mental health problems — especially among youth — from getting so bad, Kinsley said. But that can’t be all it does. It also has to spend and improve centers that deal with those in crisis now and in the future.

“The department has a commitment to making sure we get more upstream because an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, 100 percent,” Kinsley said. “But like Sen. Burgin said, we cannot close our eyes, click our heels and stop paying for crisis levels of care and hope that the upstream stuff will be there. We have to do this all at the same time and it’s going to take all of us pushing to do it.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply