by Jordan Green

Bonnie & Clyde, a musical produced by the Livestock Players for the Drama Center of City Arts in Greensboro, opens with a 15-year-old Bonnie Parker in small-town Texas pining in song for the glamorous life she’s seen in photos of starlets and flappers, quickly followed by an equally young Clyde Barrow offering up an homage to his hero Billy the Kid.

Thence forward, the eventual lovers’ path towards crime and mayhem seems inevitable as the economic ravages of the Great Depression set in, sheriff’s deputies become instruments of foreclosure and honest people find themselves shut out of the workforce.

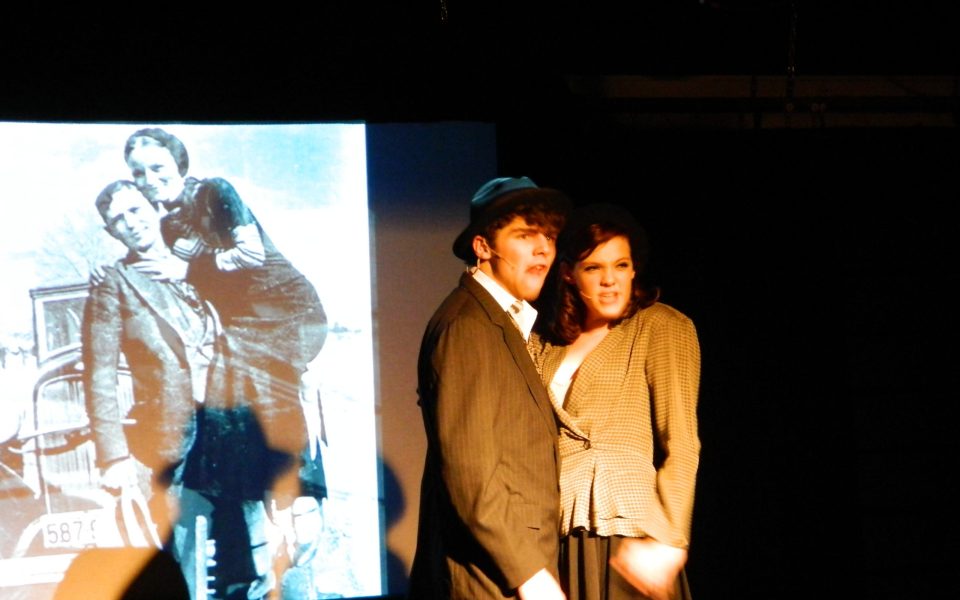

The Nov. 21 production of Bonnie & Clyde at the Stephen D. Hyers Studio Theatre in Greensboro showcased the magnetic stage presence of Rachel Walker and Aaron Boles, respectively a junior at Northwest High School and a junior at Reidsville High School, as Bonnie Parker and Clyde Barrow. The production also ably paired a talented ensemble cast with a minimalist set to create a compelling sense of the social context of the outlaws’ individual exploits.

While Barrow’s path is already set through a sequence of arrests and jail stays when the couple first meets, Parker’s decision to join him is harder to understand. A sequence of ensemble scenes in a gossipy beauty parlor, a church imbued with simple religiosity and a diner struggling to stay in business underscores a sense of confinement and privation that makes Parker’s choice seem irresistible.

Barrow and Parker’s transgressions are enabled by a broad circle of complicity: Buck Barrow, the adoring younger brother, played by Andrew Brodeur, who eventually joins Clyde; and Buck’s resentful wife, Blanche, played by Tori Galloway, who is dragged into the enterprise through her efforts to rescue her husband from criminality, along with the parents of the outlaws, whose misgivings are mitigated by cash and dutiful visits.

Those who bear responsibility for reining in the outlaw couple and their gang are also portrayed sympathetically, particularly the earnest sheriff’s deputy Ted Hinton, played by Alex Acuff, whose unrequited affection for Parker fuels a burning rage to bring Barrow in particular to justice. Mickey Hyland effectively portrays the beleaguered Sheriff Schmidt, who comes across not so much as a tyrannical lawman as an under-resourced public servant. And Jim Freeman, who also plays the judge, gives a compelling vocal performance as the embodiment of stern compassion in preacher’s robes.

The Livestock Players’ production of Bonnie & Clyde inverts the dominant cultural framing of the Depression as a time of working-class solidarity and national cohesion, as promoted by artists ranging from John Steinbeck to Woody Guthrie. Bonnie & Clyde gives us the dark side of social coping during the Depression. As each successive robbery and murder further forecloses on the possibility that Parker and Barrow will be able to go straight and make a fresh start, their path takes on a perverse logic. Those watching the play who are roughly familiar with the actual story of the outlaw couple will sense early on that Parker’s aspirations for fame and glamour will be fulfilled through the complicity of a news media that is only too happy to sensationalize their exploits. As death becomes ever more inevitable, the story takes on an apocalyptic cast, with Bonnie Parker angrily exclaiming to Blanche Barrow that a god interested in salvation wouldn’t have let the land dry up and blow away as dust.

The poems Parker writes to chronicle the couple’s exploits and the photos found in their Joplin, Mo. hideout — published contemporaneously in newspapers and projected on the wall during the Nov. 21 theatrical production — both serve to enshrine the legend.

In a way, the exploits of Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, are the equivalent of the Manson Family murders of the late ’60s: a string of sensational, media-fed crimes that captured the dark zeitgeist of their respective ages. They help us understand something larger about what was transpiring in the culture at the time.

The nine-member ensemble that provides a soundtrack for the production deserves recognition. Delivering backing to the actors’ vocal performances, while also scoring the play’s narrative development, the ensemble moved deftly between hillbilly romps and cabaret sophistication. The ensemble really cooked, particularly with a Charlie Daniels-style Southern rock number replete with guitars and fiddle that, while out of sync with the period also underscored the timelessness of this American story.

When Aaron Boles, as Clyde Barrow, exclaims after attempting to rob a failed bank, “No money in a bank — what the hell is this country coming to?” it reveals something essential about the economic conditions of the Depression.

And when Rachel Walker, as Bonnie Parker, angrily declares, “Me and Clyde Barrow are the only ones alive,” it’s easy to buy in to the sentiment.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply