Like virtually everything else in American politics, the mutual exclusion between the narratives through which Democrat and Republican partisans view elections is nearly complete. But unlike, say, guns, abortion or same-sex marriage, elections are the most important institution of democracy. Without confidence in the fair and impartial administration of elections, governance defaults to brute force.

In Guilford, the third most populous in North Carolina, at least one black voter if not two were improperly asked to show ID by white poll workers at a racially mixed precinct in west Greensboro. And at the Bethel AME Church polling place, which serves a neighborhood wedged between NC A&T University and downtown Greensboro, in what Guilford County Elections Director Charlie Collicutt described as “a major irregularity,” poll workers allowed 11 people who were not registered to vote on machines, casting irretrievable ballots.

There aren’t a lot of people talking about these incidents because the affected races weren’t close enough to tip the balance in one direction or another. But in two years we’ll have a hotly contested election between moderate Democrat Roy Cooper and ultra-conservative Republican Dan Forest for governor, a US Senate race and Trump’s re-election bid on the ballot in North Carolina. If the contests are close and any of the votes are in dispute, it’s a good bet that either of these currently obscure facts are likely to be selectively cited by partisans on either side to build a case for the other side’s bad faith.

Let’s rewind to recall how we got here. In 2013, following the US Supreme Court’s Shelby v. Holder decision, Republican lawmakers in North Carolina approved the most repressive election law in the nation by stacking a series of measures governing early voting, provisional ballots and voter ID in a way that consistently disadvantaged black voters, and the federal courts rightfully ruled in 2016 that the law “target[ed] African-American voters with almost surgical precision.”

That year, Republican-Gov. Pat McCrory baselessly accused Democrats of stealing the election before eventually conceding to Cooper. Also, after the 2016 election, Trump claimed without evidence that he would have won the popular vote “if you deduct the millions of people who voted illegally.” And earlier this month, Trump demanded that the election be called for Rick Scott and Ron DeSantis, respectively the Republican candidates for US Senate and governor, based on election-night totals, claiming preposterously that “large numbers of new ballots showed up out of nowhere, and many ballots are missing or forged,” while ignoring the fact that state law allows for overseas absentee ballots from military service members to be received days after the election.

Republicans often claim that fraud is rampant, while Democrats often argue that it’s rare to nonexistent. The facts at the granular level of local elections rarely conform to either narrative.

Marcus Brandon, a former Democratic state lawmaker, said he was dropping off a volunteer at the Muirs Chapel United Methodist Church polling place in west Greensboro on Election Day when a woman flagged him down and told him: “They’re only asking black people for ID.”

The white Republican chief judge acknowledged in an interview with Triad City Beat that one of the poll workers improperly asked two people for ID before she told him he shouldn’t do it.

But another voter who appeared at the polling place hours later — a black woman — said poll workers asked her for her ID. The chief judge disputes the claim. (North Carolina voters approved voter ID in a referendum in the 2018 election, although the details haven’t been hammered out, and the law wasn’t in effect for this election.)

In G67, a predominantly Democrat and African-American precinct adjacent to A&T, Collicutt informed the Guilford County Board of Elections that 11 voters who were not registered walked into the polling place and voted. The poll workers did not offer the voters provisional ballots, as directed by policy, or call in to the office for guidance.

“And they let those voters vote on the voting machine,” Collicutt said. “It is not a retrievable ballot. Those votes are cast anonymously. One of them we found could have been a provisional ballot if they’d been done that way, but we’re missing other essential information that’s not on here. This is a major negative that I hate to have to report. It happened. There’s no recourse. I mean, there’s recourse with the precinct official, but as far as the results there’s nothing.”

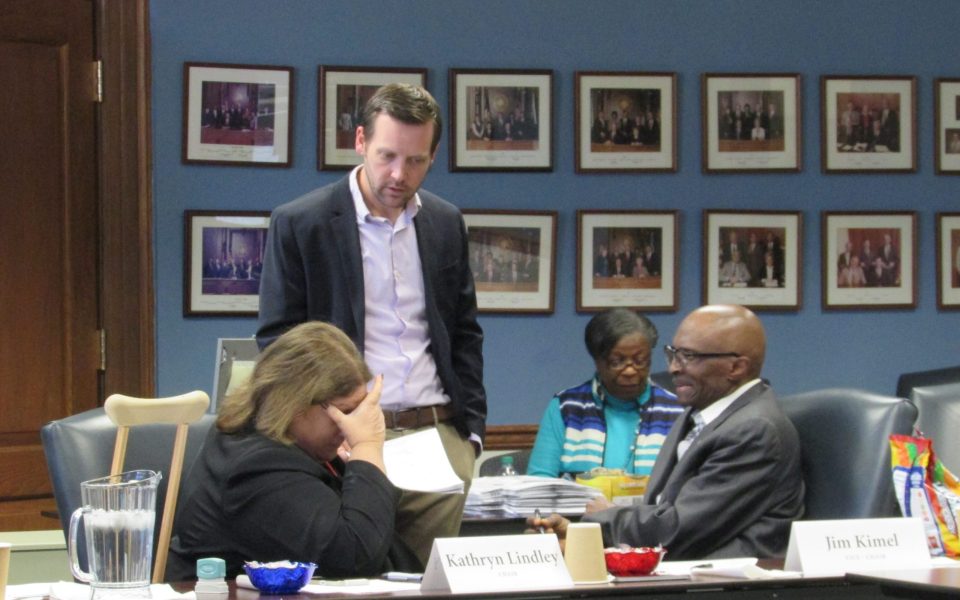

The four-member bipartisan Guilford County Board of Elections voted unanimously to refer the 11 voters to the State Board of Elections for investigation and potential prosecution. Collicutt said all poll workers, who receive nominal compensation, are up for re-appointment, and he’ll address the issue with the party chairs who nominate them before the next round of appointments.

The board also voted unanimously to disapprove provisional ballots by two voters who had previously voted at precincts G04 and G68 — the polling place for the latter is on the A&T campus — and then went to G67 and attempted to vote a second time. Collicutt said in those cases the poll workers at G67 took appropriate action and called officials at the other polling places to confirm that they had already voted, and then offered the voters retrievable provisional ballots.

The board also disapproved 111 provisional ballots cast by voters who were once registered in Guilford County but had subsequently registered in other counties, and referred them to the state for investigation. In all, the local board referred 178 voters to the state for investigation and potential prosecution.

File this under: May or may not become relevant at a later date.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply