For Frederic Church, painting became a lifelong pilgrimage in a search for transcendence.

During the post-Civil War period when many artists were still focused on neoclassical and religious themes, and more banal depictions of nature and American life, Church’s romantic vision reached beyond a nation at war, to the expanding west and the farthest reaches of the globe, capturing not only what the natural landscapes hold, but the feelings it produces in those who witness them.

Frederic Church: A Painter’s Pilgrimage at Reynolda House Museum of American Art, which runs until May 13, focuses on his journey and artistic growth, a search for inspiration that took him to places that existed only in myth and legend to the American public of the 19th Century.

Reynolda House, which holds Church’s 1855 masterpiece “The Andes of Ecuador” in its permanent collection, is one of only three venues hosting the exhibit that was organized by the Detroit Institute of Arts. The primary focus of the exhibit is that of Church’s journeys to the Middle East, Greece and Rome from 1867 to 1869. Church was the first major American painter to visit the locations. With the notion of sharing foreign landscapes and architecture with the American public, Church’s travels also held a personal purpose.

[pullquote]To learn more about Frederic Church: A painter’s pilgrimage, visit reynoldahouse.org.[/pullquote]In the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War and the death of his two small children in 1865, Church turned his artistic eye from nature towards history, specifically history as it touches on the natural world. He wanted to see the ruins of once-great civilizations and where they stood, with hopes of dealing with the loss that affected his country as well as his own personal sorrow.

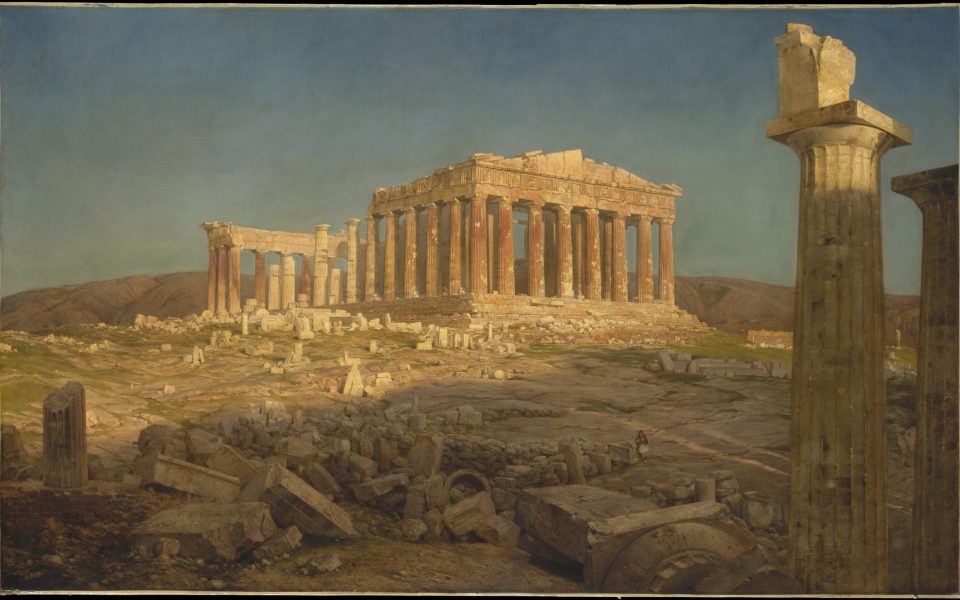

Church’s expansion into historic themes can be seen most aptly in his 1871 painting “The Parthenon,” completed a few years after his visit to Greece. Though on first glance, Church’s famous use of color and luminism catches and directs the eye to the glowing ruins caught in the waning afternoon light, there is still much more at play on the canvas measuring in at almost six feet tall. In the lower horizon of the work, we see the ancient ruins covered by shadow and time, reduced to mere rubble among the dirt. While against an expanse of blue sky, golden sunlight rests heavenly on the still-standing structure of the Parthenon’s columns, making them glow in the most sacred of ways, though the threat of shadows and dust prey at the footsteps of this once magnificent edifice. The light becomes the focus of the scene, one of Church’s signature features, as if starkly illuminating humanity’s accomplishments, while also showing its fleeting nature and the brevity of life.

Caught nearly at the exact center of the painting is the tiny image of a man, leaning against the smooth edge of fallen brick. Commentary had rarely entered into Church’s works until the late 1860s. The painting acts as a sort of meditation on civilizations and humans’ lust for power. While societies have been able to achieve greatness, the artist seems to argue for a recognition of the infinitesimal place human beings hold in the universe. The idea shook Church’s audience at the time and speaks to the current climate of the world.

Among the finished masterpieces in the exhibit, the public is allowed, for the first time, to see Church’s numerous sketches and plans for what would become his renowned works. On rare display is Church’s great post-pilgrimage work on his estate he named Olana, sitting upon a high hill overlooking the Hudson River, north of New York City. Taking inspiration from Middle Eastern architecture and ornamentation, blended with his own aesthetic and spiritual ideals, Olana consumed Church’s sole attention for well over three decades. The exhibit reveals the architectural drawings that Church created while planning his Persian-style temple on a hill.

The Church exhibit at Reynolda House displays the artist’s vision and journey into realms and landscapes that were thought inaccessible. Moving linearly from the pilgrimage’s start until its effects on the artist thereafter, the exhibit allows a rare view into the growth of one of America’s most lauded masters of art and his search for answers in the world’s most remote landscapes.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply