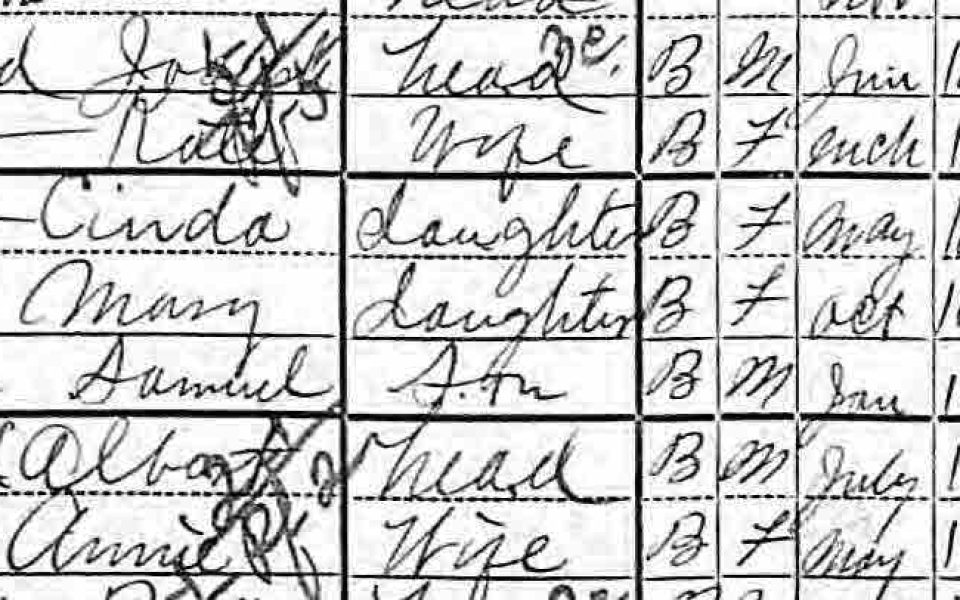

Angenita Boone gestures to the images projected on the screen. She motions to the rows of names, scrawled in cursive and points out the surname of her grandmother’s ancestors — Gailyard. Printed next to some of the names is an abbreviation: ‘neg.’

“‘Neg,’ that’s negro,” Boone explains. “Some have ‘M’ for mullatto and that means you’re mixed or something, but some black people would have a ‘W’ because you looked white cause [they] didn’t ask and you didn’t want to tell [them].”

The abbreviations come from lines on a federal Census dating back to the mid 1800s. Boone stands at the front of the Sally Gant Classroom at Old Salem, where sepia-toned maps of Southern states decorate the walls. Several dozen enthusiasts have come to listen to her workshop, The Basics of Genealogy Research, as part of the 2019 Black History Month Genealogy Conference on Feb. 2.

Halfway through the talk, Boone reveals an unsettling finding: her ancestor’s owners. She describes how she worked backwards up her family tree, starting with her grandmother, until she found a pension record for a relative who served in the Civil War. Using that piece of information, she discovered the man who owned some of her relatives.

“I was happy and elated to find that’s why our last name was Gailliard,” Boone says. She incorporated the slave master’s family tree into her own. “Their history is my history,” she says.

The workshop demonstrates the mission of the conference hosted by the Afro-American Historical Genealogical Society: to research and discover the history of African Americans in the United States. For Boone, that means uncovering some uncomfortable realities.

“They had a hard life,” Boone says about her ancestors. “There’s nothing you can do about it. You just want to know what life was like and how they struggled, and you want your children to pass on that information. It doesn’t make life any better or worse. I’m not mad with anyone, it’s just about finding out the truth as best you can.”

The conference, which was held at Old Salem for the first time this year, was hosted in part due to Old Salem’s recent initiative, Hidden Town, which aims to reveal the history of enslaved and free Africans and African Americans who lived in Salem.

Martha Hartley, director of Moravian research at Old Salem and co-chair of Hidden Town project, says hosting the conference was a natural fit for them.

“We want to locate where enslaved people lived and integrate narrative into the visitor experience,” Hartley says. “We want to connect with descendants to help make the story real.”

For years, a tour of Old Salem has been a given for elementary and middle school field trips, but the stories of slaves and black people who lived in the town remained unshared. Projects like Hidden Town and the genealogy conference look to change that.

Bryana Campbell, a member of the genealogical society’s North Carolina chapter says she remembers school trips to the historical town.

“I remember the bonnets and the weird clothes,” Campbell says. “But I had no idea about the slave community or black community in Old Salem. It makes people know that our people were here. We have to reclaim our history.”

Campbell, who is white on her father’s side and black on her mother’s, says she began researching her family line a few years ago.

“My dad is white, so there’s more records for him,” Campbell says. “There were more people researching and for the most part, they had the tree done. My mom is more difficult. There are fewer records. I expected it but it’s aggravating. They’re people too, so why are they treated any different? Why aren’t there records kept for them?”

Boone explains in her workshop that slaves weren’t counted for the Census until 1870, almost 100 years after the first official Census in 1790. And even then, many had names misspelled or were omitted entirely.

“It’s not that they never lived,” Boone says. “It’s that they were missed, maybe.”

For those starting out, she recommends starting with the 1940 Census which is the last census released to the public. Decennial Censuses take 72 years to be publicly released because of confidentiality rules. Boone emphasizes the importance of tracing family lineage for future generations and lists the types of documents that can help trace family trees for free, without the use of programs like Ancestry.com.

“Marriage certificates or death certificates are free,” Boone says. “So, when there’s snow on the ground and you have nothing to do, go ask your relatives, ‘Who’s this, who’s this?’ Because when they die, no one will know.”

Velda Holmes, a retired EPA worker from Durham, rose early on Saturday to drive to Winston-Salem for the conference. She says she’s been able to trace her mother’s side of the family back to 1866.

“I didn’t know to trace back to the slave owner,” Holmes admits. “It was interesting to hear her talk about that and the documents she found. I’m excited about trying to do that when I get back home.”

Holmes says she’s become the designated family historian. She plans to share her latest findings at her family’s 62nd family reunion.

“I think that for us to stay connected, we need to know as much as possible about our family,” Holmes says. And for her, that’s everything, including her family’s history of being enslaved.

“It was what was going on at the time,” Holmes says. “Good or bad, that is part of your history. The information is out there. You just have to go search it out and once you do that, share it.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply