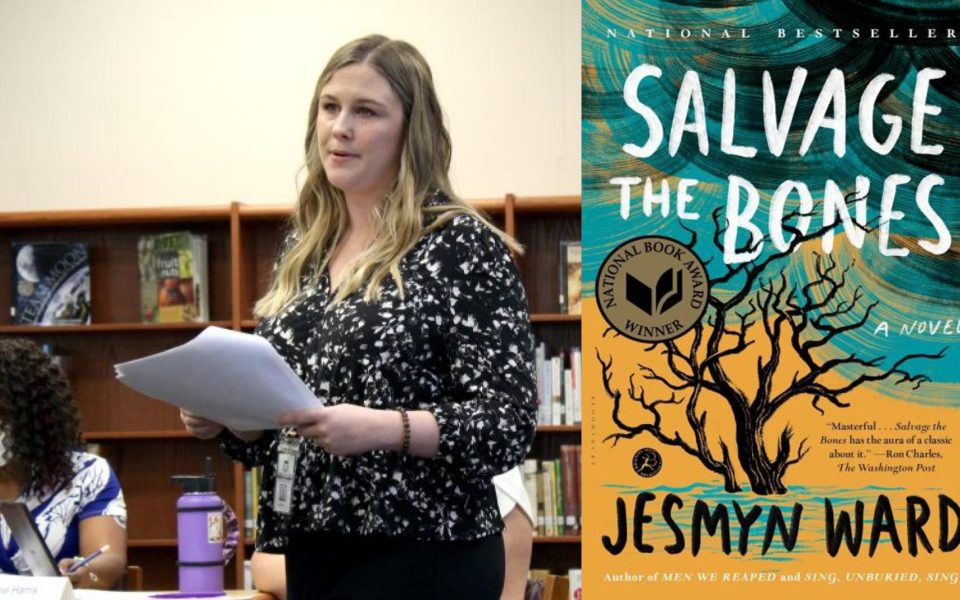

Featured photo: Northern Guilford High School English teacher Holly Weaver is currently fighting a book ban that challenges ‘Salvage the Bones’ by Jesmyn Ward.

UPDATE: On Thursday afternoon, 12 members of the Northern High School Media and Technology Advisory Committee voted to retain ‘Salvage the Bones’ on the AP Literature syllabus, and to retain it in the school library, while one committee member voted to remove the book from the curriculum and from the school library. Because the school library had not carried the book before now, a copy will be provided, according to a committee spokesperson.

AP English teacher Holly Weaver looked confident as she stared out into the crowd. Her long, blonde hair fell past her shoulders as she spoke directly to nearly 100 people who had gathered in Northern Guilford High School’s library on Thursday morning. Her voice never shook, never quavered. And why would it? Weaver, who has been teaching in public schools for the last eight years, is used to this; she does this every day. She gets up in front of room and talks about literature and themes and motifs, just like she did this morning.

“Sometimes, the human experience is controversial,” Weaver said during her presentation.

And it was controversy that brought Weaver to defend a book at Thursday’s public hearing. For the last several weeks, the Northern High School English teacher has been involved in a resource-challenge process after mothers of two of her students took issue with a book she assigned as part of her AP English class’s curriculum. The book, Salvage the Bones, is a 2011 novel written by Jesmyn Ward, who is the only woman and only Black author to win the National Book Award for Fiction twice. The first time was in 2011 for the exact book that is currently being challenged by parents Elena Wachendorfer and Kimberly Magnussen. The second time Ward won the title was in 2017 for her book Sing, Unburied, Sing.

What is the process for challenging books in Guilford County?

Per Guilford County Schools’ rules, concerns over resources are typically sent to the school’s official, often the principal, who explains the school district’s resource-selection policy, then encourages the complainant to meet with the teacher for discussion. Teachers are then to offer the students an alternative resource. If the concern is not resolved at that point, then a form can be filled out by the complainant, which gets forwarded to the school’s Media and Technology Advisory Committee’s chairperson, who schedules a public meeting. The committee members must read and review the challenged resource to deliberate on whether they will keep the resource, remove it, or keep it but with restrictions. The public meeting lasts just one hour and if the committee does not have time to deliberate within the hour, then another meeting is scheduled within the next five school days for members to meet and make their decision. Once their decision is made, the teacher and the complainants are notified, and if the complainants are unsatisfied with the committee’s decision, they can submit a different form which will go to a higher-level District Review Committee. That committee will follow the same process as before and hold an hour-long public hearing in which they’ll hear from the teacher and the complainants to make their decision. If the complainants are still unhappy with the result, they can appeal to the school board and superintendent by filing another appeal form.

According to public records requested by Triad City Beat, Wachendorfer and Magnussen submitted forms in mid-April urging the removal of Salvage the Bones from the school, calling the novel “trash,” “garbage” and “pornography.”

During her presentation, Weaver noted that of the 104 students in her English classes, only five students took issue with the book. She also taught the book last year in her AP English class, which is optional, and the book was well-received by students, many of whom told her the book was their favorite of the year. Weaver also told her students when she assigned the book that it contains descriptions of violence, sex and profanity and if they wanted, they could skip certain passages that made them uncomfortable, or read an alternative book altogether. Five students moved forward with the alternate option, but two of the students raised their concerns with their parents who initiated the challenge process.

Why is this book being challenged?

Since its publication in 2011, Salvage the Bones has not only won the National Book Award for Fiction, but has also been praised by critics across the country. Following a working-class Black family living in southern Mississippi in 2005 right before Hurricane Katrina, the book tackles issues of race, poverty, sex and gender, mostly from the perspective of Esch, a 15-year-old Black girl. During her presentation, Weaver explained to the crowd — which was mostly made up of supporters including fellow educators and current students — that she chose the book for its various themes, symbolism and complex characters.

“This novel contains themes that will always be relevant,” Weaver said. “Teenagers will have to navigate their world, and yes, that world does involve uncomfortable topics like statutory rape and teenage pregnancy. However, this book also shows the timeless themes of family loyalty and resilience. Moreover, the themes in this work are incredibly nuanced and complex.”

The parts of the book that Wachendorfer and Magnussen took issue with include passages that depict Esch being coerced into having sex with a 19-year-old male. During their comments Wachendorfer and Magnussen argued that the book was “pornographic” and “tacky.”

As they read from the book, students in the audience rolled their eyes and snickered. Others shook their heads.

“That’s pedophilia, depicting sex between an adult and a child, a minor,” Wachendorfer said. “We know this happens in the real world, but what value does this add to the story?”

Wachendorfer then went on to argue that “porn is not protected free speech.”

Magnussen, who spoke next, cited similar lines of argument during her allotted 10 minutes.

“Why not choose a book that deals with issues of poverty class struggle, hardship, natural disaster, ethnic and cultural values minus the offensive language and obscene and sexual content in a way that doesn’t sugar coat these issues but showcases the rising above and overcoming?” Magnussen said. “There is no value in lewd and sexual depictions.”

Despite Magnussen’s urging to teach without “sugarcoating” issues, Weaver’s argument in favor of Salvage the Bones expressed that the parents’ efforts to ban the book was just that.

“When asked why she wrote Salvage the Bones, Jesmyn Ward notes her desire to not let Hurricane Katrina fade away from the public consciousness,” Weaver said. “She says, ‘I realized that if I was going to assume the responsibility of writing about my home, I needed narrative ruthlessness. I couldn’t dull the edges and fall in love with my characters and spare them. Life does not spare us.’

“Some of us many never know what it’s like to be poor,” Weaver continued. “We may never know what it’s like to be Black; we may never know what it’s like to be a pregnant teenager; we may never know what it’s like to be the only girl in the family. But thank goodness for literature. Thank goodness reading allows us to walk in someone else’s shoes, even if only for a few hundred pages.”

During her presentation Weaver also noted that the book was on an approved list of AP course texts and has been endorsed by multiple curriculum specialists. One of the most impactful moments of the hearing came when Weaver pulled up a video recorded by author Jesmyn Ward herself in which she talks about why she wrote the book and urges the committee to keep it in schools.

“I’m not here to convince anyone of anything beyond saying that this is a story about family, about love, about real issues and circumstances that young people confront every day,” Ward says in the video. “It is the artist’s work to examine all parts of the human experience with the goal of getting at deeper truths; that’s my aim. I hope you’ll continue to allow Ms. Weaver to teach your children about experiences that differ from their own. There’s so much that we can all learn from each other.”

Two students who attended the public hearing on Thursday held signs in support of Weaver that read, “Reality should not be banned” and “Banning Books = Hiding the Truth.”

Naiya McKnight, a 12th grader in one of Weaver’s English classes, said she showed up because “silencing the voice of young African-American women won’t silence the experiences that they go through.” McKnight, who is Black, said she enjoyed the book even though it was hard to read because it was important to have uncomfortable conversations. Next to her, senior Peyton Clendon said that she and the other students are mature enough to make decisions for themselves on whether to read the book. If students don’t like the book, they can read the alternate, she argued. But the book shouldn’t be banned for all students.

“She gave us other options,” Clendon said. “She’s going the extra mile. She shouldn’t be discarded as a bad teacher for that.”

Now what?

After hearing from both parents and Weaver, the 13 members of Northern High School’s Media and Technology Advisory Committee gave their own statements. The committee is made up of nine staff members — including teachers of various subjects — and three parents and one student.

Andrew Hulberg, a social studies teacher at Northern, said that when he first learned about the book from his son, he was shocked by the content but that through conversations with his child, they came to understand why the novel was part of the curriculum.

“It was not what he was expecting, but he kept reading and kept wanting and kept seeing and that’s what I’ve always encouraged my child to do,” he said. “If a book challenges this and the book does have uncomfortable content, I will not deny that the book has done its job. And I need my child to be a great thinker, especially going forward to see alternative perspectives.”

Another member of the committee, parent Karin Rochester, said that the difficult topics depicted in Salvage the Bones are important for students who may have lived sheltered lives.

“We as parents forget that some of our kids grow up in such a bubble, they don’t understand that some kids’ lives are very different than what they are experiencing personally,” Rochester said.

Located in the northern part of Greensboro near Summerfield, Northern Guilford High School has a majority-white student population and the school has one of the lowest rates of students who get free or reduced lunch.

“This book is not pornography,” Rochester continued. “This book is a young girl’s pragmatic account of her life…. It is fiction, but I’m sure it’s not fiction for someone…. When our lucky, protected children read about her horrible situation, they should be shocked…. How about instead of focusing on how graphic the portrayal of her life is in the book, we asked our AP Lit seniors how learning about the rough home lives that some people are born into can become a call to action to improve life for others in our country and in our world?”

Of the 13 committee members, only 10 were able to speak within the allotted hour. Three — including a student, Assistant Principal Monique Wallace and Media Specialist Annie Harris — did not get the opportunity to speak. This means that a closed session will be scheduled within the next five school days for the committee to meet again and make a decision. That meeting will not be open to the public. And while an official decision has not yet been made, every member who had time to talk spoke in favor of keeping the novel at the school.

On Thursday afternoon, Weaver said that she felt hopeful that the committee would reaffirm her stance to keep the book within schools.

“I’ve seen many positives come out of this conversation,” Weaver said. “I have received a number of emails from colleagues, students and parents in support for keeping the novel…. I’ve been warmed to see our community stand up for their freedom to read. These conversations are a reminder of why I love teaching English literature.”

Weaver, who is finishing out her second year teaching at Northern, said that before this whole process started, she submitted her resignation letter to the school.

“I am planning on moving to the Asheville community to be closer to my family,” she told TCB. “I’m unsure of what I will be doing in the future, but I hope that I will still have a place in education.”

How and why book-bannings are spreading across the country

According to Guilford County Schools Media Services Director Natalie Strange, this is the first resource challenge that the school district has seen in a while.

“We have a large student population, nearly 70,000 students, over 114 school libraries that operate,” she said. “So looking at that total population, I’m not seeing a glut of resource challenges.”

Other schools in the state and across the country have been busier.

According to an April report by PEN America, a literary and free expression advocacy organization, school districts in 26 states banned or opened investigations into more than 1,100 books from July 2021 to March 2022.

“Over the past nine months, the scope of such censorship has expanded rapidly,” the report states.

And that mirrors what advocates are seeing in North Carolina, too.

“Here in North Carolina, in several counties, people are showing up and insisting that the schools — whether they’re pressuring the school principals, the librarians, or the school boards —remove books from the reading lists or from the shelves in the local libraries,” said Janice D. Robinson, the NC Program Director for Red, Wine and Blue, an organization that channels the collective power of suburban women. “They’re showing up to get public libraries to remove books, too.”

According to a map on Red, Wine and Blue’s website, many of the resource challenges are happening in the central part of the state in counties like Chatham and Moore. In nearby Wake County, conservatives successfully moved the public library system to permanently ban Gender Queer, a 2019 memoir by author Maia Kobabe, from their shelves. The graphic novel deals with what it means to be gender nonbinary and asexual. In Union County, Superintendent Bill Nolte removed Nic Stone’s 2017 novel Dear Martin from schools after receiving one parent complaint. The book chronicles how an Ivy League-bound Black student becomes the victim of racial profiling.

Across the nation, a vocal conservative movement has been making the news after targeting a variety of texts including ones with LGBTQ+ perspectives to ones that deal with racial injustice. Other titles that have been targeted include classics such as Toni Morrison’s Beloved and the Bluest Eye. Graphic novel Maus, about the Holocaust, has also been challenged in multiple school districts.

“It’s a continuation of making CRT a boogieman issue,” Robinson said. “No elementary teacher is teaching their kids CRT. That is a big lie to scare people into thinking their kids are being indoctrinated.”

It appears the rhetoric is trickling place at the national level. Across the country, lawmakers are introducing bills that aim to restrict what teachers can teach in schools, including topics like gender and racial identity. In NC, Lt. Governor Mark Robinson has been one of the most vocal proponents of this movement.

“He’s alleging all sorts of things like books are pornography or grooming going on in public schools,” said Todd Warren, a statewide campaign strategist with Down Home NC. “One of their favorite words to use is ‘indoctrination’…. But it’s so clear that it’s an outright attack on Black and brown students and LGBTQ+ students and staff.”

According to Warren, banning books is just the newest issue that’s been taken up by the conservative movement in this country.

“It started by being anti-mask, then it was anti-CRT and now it’s moved into censorship and book-banning,” Warren said. “What all of these things have in common is they focus on essentially what is a nonissue for the day-to-day functioning of schools…. They don’t want to talk about what schools really need which is funding and resources and staffing.”

Part of the strategy, according to Warren and Robinson, is using topics like book-banning to rally the base of the GOP to win elections. In both Guilford and Forsyth Counties, many school-board candidates for the midterm elections ran on a platform that fell in line with the national conservative fearmongering rhetoric about CRT and LGBTQ+ issues in schools.

“You’ve got a strategy coming directly out of Steve Bannon’s War Room,” Warren said. “The strategy is to enflame racial tensions and gender identity with the hope of mobilizing their base which they increasingly know is in the minority. They are doing it in ways that appear to be organically arising everywhere, but it’s actually a very well-funded movement that is targeting certain electoral districts.”

And that’s a problem because the majority of the country is against banning books, according to national polling. A poll conducted in mid-February of this year by CBS and YouGov found that “83 percent of Americans believe no book should be banned for criticizing US history, and 85 percent said no book should be banned for presenting political ideas they don’t agree with. A healthy 87 percent of Americans surveyed believe no book should be outlawed for discussing race and slavery.”

To combat this wave, Warren said that community members need to do what they did Thursday morning: show up in support of teachers and librarians and school boards to keep books in schools.

“The people who do the work of representing our schools need to hear from the majority because there’s a very loud voice in the room,” Warren said. “Because it could get tiresome over time. They need to know that parents by and large are happy with their schools.”

That kind of support matters for teachers like Weaver.

“This experience has been a lot of emotional labor,” Weaver said. “Usually my evenings or weekends are spent working on lessons or grading but this situation has been incredibly distracting and exhausting.”

While she doesn’t know where she’ll end up after leaving Guilford County Schools, Weaver said she wants her experience to motivate other educators to fight against book banning moving forward.

“While this experience has been difficult, I want the teacher reading this to know that they shouldn’t be afraid of the national book banning trend,” Weaver said. “It is going to take a community of parents, administrators, teachers and students to stand up for the freedom to read, and from my experience, many people are willing to take that stand. I believe there is integrity in this world.”

The hearing where the committee will finish deliberating and make a decision about the book has not yet been scheduled according to Guilford County staff. TCB will continue to follow this story and make updates as needed.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

[…] Guilford High School (NC) addresses the board about the power of that book and why she uses it (only 5 students have complained). ““We are asking our community to please not follow Representative Patterson’s example of […]

[…] The instructor who assigned the “controversial” e book Salvage The Bones in Northern Guilford Excessive College (NC) addresses the board in regards to the energy of that e book and why she makes use of it (only 5 students have complained). […]

[…] The teacher who assigned the “controversial” book Salvage The Bones in Northern Guilford High School (NC) addresses the board about the power of that book and why she uses it (only 5 students have complained). […]

[…] The teacher who assigned the “controversial” book Salvage The Bones in Northern Guilford High School (NC) addresses the board about the power of that book and why she uses it (only 5 students have complained). […]

[…] The teacher who assigned the “controversial” book Salvage The Bones in Northern Guilford High School (NC) addresses the board about the power of that book and why she uses it (only 5 students have complained). […]

[…] Guilford High School (NC) addresses the board about the power of that book and why she uses it (only 5 students have complained). ““We are asking our community to please not follow Representative Patterson’s example of […]

[…] Guilford High School (NC) addresses the board about the power of that book and why she uses it (only 5 students have complained). ““We are asking our community to please not follow Representative Patterson’s example of […]

[…] The teacher who assigned the “controversial” book Salvage The Bones in Northern Guilford High School (NC) addresses the board about the power of that book and why she uses it (only 5 students have complained). […]

[…] The teacher who assigned the “controversial” book Salvage The Bones in Northern Guilford High School (NC) addresses the board about the power of that book and why she uses it (only 5 students have complained). […]

[…] The teacher who assigned the “controversial” book Salvage The Bones in Northern Guilford High School (NC) addresses the board about the power of that book and why she uses it (only 5 students have complained). […]

[…] The teacher who assigned the “controversial” book Salvage The Bones in Northern Guilford High School (NC) addresses the board about the power of that book and why she uses it (only 5 students have complained). […]

[…] brings us to the third interesting thing about the novel: its recent challenge in Guilford County, North Carolina over its inclusion in an AP English class. Two students took offense at the book, […]

[…] librarians wrote about preparations for budgets for small spaces, efforts to ban books at public libraries, teaching computer skills in rural Vermont, different library jobs on the rise, the library in […]