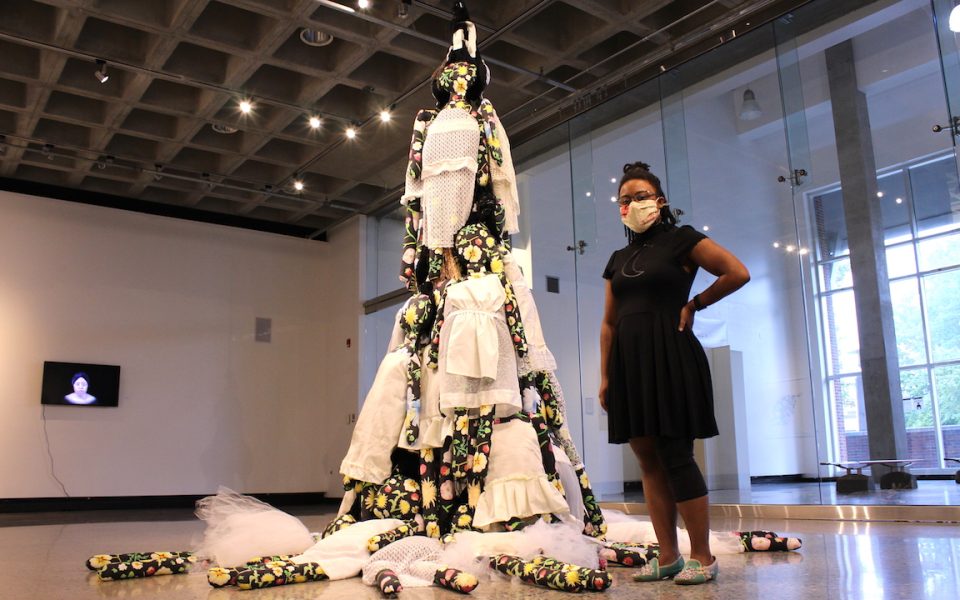

Artist Jasmine Best stands next to her piece, “Pulled Out At the Root,” in the Gatewood Gallery at UNCG. (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka)

The figure kneels in front of the spectator in a subservient pose, her arms bent forward in offering and her head bowed low, obscuring her face. Dandelions and wild strawberries ornament her pitch-black body. Her name is “Baby Girl.”

“It was a specific moment,” artist Jasmine Best remembers. “I was like a tween, maybe 12 or something like that. I was at a cookout, a friend of the family’s. The cookout had slowed down and everyone was outside chilling. I was inside… and this guy comes in and he’s just like ‘Can you make me a plate, baby girl?’”

Best describes her memory from more than a decade ago. She’s transported to a family friend’s cookout and is minding her own business when a man comes inside the house and asks her to fix him a plate. She doesn’t know him. This isn’t her house. She just looks at him until he realizes she’s not going to get him anything.

The memory is solidified in the form of a large, digital and gouache painting by Best which hangs on a wall in the Gatewood Gallery at UNCG. “Baby Girl” and other paintings in the series describe names that the artist has been called throughout her life and the subsequent feelings that arose when she was called them.

“That’s how I was thinking about this pose,” Best says about the painting. “If you’re about to present a platter in a bowing motion because the expectation there was for me to just jump up and be like, ‘Oh yeah! No problem.’ But in reality, it was like, I don’t know you, I don’t know why you felt comfortable calling a strange 12-year-old girl ‘baby girl.’”

The piece encompasses the core message of Best’s new show at the gallery titled, American Weeds Growing Through Docile Garden, which opened on Aug. 21 and runs through Sept. 13.

“This show was born out of a few different experiences I had where I was seeing that there wasn’t as much callout to misogynoir both in and outside of the Black community,” Best says. “I’m not always the best at communicating with people, which is why I think I make art. So, I thought that the best way to discuss it was to create pieces around it.”

Throughout the show, Best tackles issues of sexism and racism and microaggressions surrounding her experience as a Black woman. She parallels the lives and labor of Black women and femmes with weeds that were brought from other parts of the world to America to serve a specific purpose, only to be cast aside and demonized once they began to thrive.

In her series of paintings named after the show, with the Black figures that resemble bodies by Henri Matisse, Best recalls other monikers she’s been called like “negress,” “Nubian queen” and “uppity.”

“These ones were focusing on uncomfortable, unnatural positions,” Best explains. “And the idea that there’s sort of this expectation for Black femmes, and women in general, but I know there’s just this certain level of labor that Black femmes are expected to do… extra effort that goes into making other people comfortable in their presence. This idea of not just shrinking yourself but really bending over backwards to make sure other people are comfortable, whether that’s physically or socially, but it’s at Black femmes’ own expense, that could be body, spiritually, mentally or a mixture of all of those.”

On the bodies of each of the figures are luscious depictions of wild strawberries, dandelions, celandines and pineapple weeds.

“Those are all weeds that serve another purpose,” Best says. “These are things that have specific other tasks that they were brought here to do, but they’re considered weeds but the only difference between a weed and a flower is what is deemed more useful or more beautiful.”

In the center of the gallery hangs looming sculpture made up of fabric dolls created by Best. Their skins reflect the skins of the figures in her paintings and are black with the wildflowers and plants. They wear individual white dresses, each strung up into the mass by her hair. Best titled the work “Pulled Out at the Root.”

She says she learned dollmaking at a young age from her grandmothers and great-grandmothers. She came to view dolls as protectors and decided to use them to signify Black women’s pain and suffering.

“Black women are expected to die off the frame or off the page,” Best says. “Black men at least have this visualization of lynching that is often used in art and literature for symbolism, but Black women don’t. So I was stealing a little bit of that lynching symbolism, but using it where they’re held by their hair which is often a very feminine trait, and Black women have a very political history of their hair.”

Best, who started conceptualizing and working on the show a year ago, worried that by the time the show opened this year that the themes and stories she was trying to tell wouldn’t be relevant. But as the pandemic progressed and the racial justice uprisings spread across the nation, she found that her messages were more relevant than ever.

And although most of the national conversation around racial justice attempts to hold white people and white institutions accountable, Best also extends the same critical questioning to Black patriarchy.

In the most straightforward piece in the show, Best projects a claim onto a black canvas with woven letters made of found fabric. The statement is bold and clear, “Black daughters are not excuses for poor behavior.”

Best explains that the piece is part of a series of text-based works that describe sentiments that she was either “too polite or too Southern to say.”

She describes interactions she’s had with Black men in which she calls them out for saying something sexist and being met with the argument that they couldn’t be sexist because they have a daughter. She says that recent pop culture events with Kanye West, in which he talked about convincing his wife Kim Kardashian to not abort their daughter, and rapper T.I., who made headlines when he said that he makes his daughter go to the doctor regularly to make sure her hymen is intact, made Best’s statement even more relevant during the pandemic.

“It started off more as a personal thing of wanting people to stop and think about the Black women in their lives,” Best says. “Like, What are my actions doing that is affecting them? rather than being immediately defensive. Also noting that that behavior isn’t coming from nowhere…. America has a history of creating Black daughters but disregarding the behavior that is very anti-Black towards them. The Black community didn’t just get that from nowhere.”

As the pandemic rages on, Best says she unfortunately sees more and more relevancy to current events in her work. But the hope, she says, is for her pieces to create meaningful conversations between people.

“I want to create a platform for things that I don’t think people are discussing enough,” Best says. “There’s a lot of discussion around call-out culture and cancelling, but that’s not what I’m trying to do. I want people to just be more aware of what some of the people in their lives are going through.”

American Weeds Growing through Docile Garden will be on display at the UNCG Gatewood Gallery through Sept. 13. Best will host a virtual gallery talk via Zoom about her show on Sept. 10. Learn more about Best at jasminebest.com or follow her on Instagram at @jasminebestart.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply