I.

Richard Dillon, a member of the Loyal White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, and his friend, David Winebrenner, both from Hammond, Ind., arrived at the home of Chris Barker, the imperial wizard — or national leader — outside Yanceyville, NC around midnight on Dec. 2.

The living room was crowded with people who had traveled from out of state to attend a “victory” parade the following day to celebrate the election of Donald Trump. Many of them were drinking.

As the night progressed, an old argument between Dillon and William Hagen, the California grand dragon — or state leader — resurfaced regarding Hagen’s handling of a violent confrontation between the Loyal White Knights and protesters in Anaheim, Calif. earlier in 2016. At that point, Winebrenner had gone out to their vehicle to fetch a beer for Dillon, and when he returned to the house he “noticed that the environment seemed hectic,” according to an affidavit filed by John T. Ray III, an investigator with the neighboring Person County Sheriff’s Office. Dillon told Winebrenner to load up their vehicle and get ready to leave.

“Dillon stated that Hagen and Barker began to show aggressive behaviors and that Barker was encouraging Hagen to fight Dillon,” Ray wrote in the affidavit. “Dillon advised that Barker continued this behavior and that Hagen eventually stood up and unsheathed a fixed-blade knife. Dillon stated that at this point he stood up and was stabbed by Hagen — two stab wounds to the upper chest area and one stab wound to the right thumb. Dillon advised that after being stabbed, he was able to fight off Hagen [and then] was struck by Barker’s fist.” Dillon said he was confronted by someone he didn’t know as he tried to fight his way towards the front door.

Still outside, Winebrenner started to worry, and began to text his friend to see why he hadn’t come out yet. Not long after that, Winebrenner said, Chris Barker came out of the house.

©

©

“According to Winebrenner, Barker attempted to gain entry to the vehicle and later advised Winebrenner that Dillon was dead,” Ray wrote. “Barker also advised Winebrenner that he would drive him to the ATM and withdraw $2,000 in order for Winebrenner to leave. Winebrenner stated that he denied the offer and took the keys out of the ignition [and] noticed Dillon exiting the residence and still being confronted by other unknown subjects.”

The two Indiana men fled to Danville Regional Medical Center across the state line in Virginia, where Dillon was treated for his stab wounds. When Dillon came to grips with the gravity of the assault, he decided he would press charges. Dillon and Winebrenner showed up in the lobby of the Caswell County Sheriff’s Office and swore out a warrant for Hagen and Barker’s arrest.

It looked a lot like a setup to Dillon. He told Ray that Chris Barker had called him numerous times to ask if he was still coming to the Klan gathering in North Carolina despite a verbal argument in recent months over how Hagen was operating his KKK group in California. Dillon said it was odd for Chris Barker to contact him because usually when he received a call from the Barkers’ phone number it would be from Amanda.

©

©

Hagen was charged with felony assault with a deadly weapon with intent to kill inflicting serious injury — essentially attempted murder — while Barker was charged with felony aiding and abetting assault with a deadly weapon with intent to kill inflicting serious injury. Hagen, the imperial wizard and California grand dragon, would wind up sitting in jail on the day the Loyal White Knights — one of the most feared Klan groups in the country — was expected to lead a triumphal parade to capitalize on the surge of white, Christian nationalism that had swept Donald Trump into office.

The whereabouts of the parade had always been a matter of speculation and confusion, mostly by the Loyal White Knights’ design. The night before Barker had indicated to a reporter at the Burlington Times-News that the parade would take place at 9 a.m. in Pelham, an unincorporated village in the northwest corner of the county where the Loyal White Knights maintained a Post Office box.

That’s when carloads of left-wing antifascists dressed in black, many wearing facemasks, began arriving at a local rest area on Highway 29, joined by an international corps of reporters. The protesters and the press knew nothing about the violent drama that had transpired at Barkers’ house, and rumors flew as the antifascists sent out scouts on a reconnaissance mission in a vain effort to find the Klan. Eventually they tired of waiting and, armed with metal baseball bats, about 150 antifascists marched from a community center around a 1.2-mile loop carrying a banner reading “Against white supremacy” bearing an anarchy symbol and a logo that riffed on the Ghostbusters movie.

With Caswell County sheriff deputies and state highway troopers watching, the antifascists wound back around to the community center, and then piled into cars to Danville looking for the opportunity to confront the Klan. Again, they marched through the streets without encountering their adversaries. When the Loyal White Knights did make an appearance, it was 3 p.m. and not in Pelham or Danville, but in Roxboro, the county seat 22 miles to the east of Yanceyville. As Barker and Hagen sat in jail, a caravan of 20-30 vehicles sped through Roxboro as the occupants yelled, “White power!”

II.

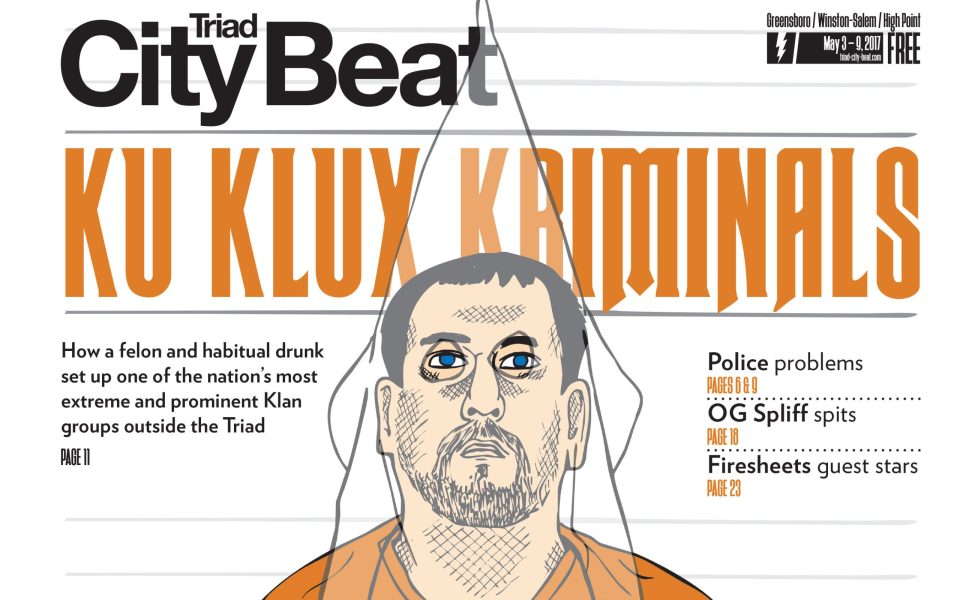

Before he founded the Loyal White Knights, Chris and his wife, Amanda, had been expelled from the Original Knight Riders Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in West Virginia for, among other offenses, “excessive or habitual drunkenness.” On an affidavit of indigency after his Dec. 3, 2016 arrest, Chris Barker indicated that his only employment was “landscape for side jobs in summer.”

The inception of the Loyal White Knights in early 2012 did not seem particularly auspicious at the time. Fliers tossed in the driveways of residents across the northern Piedmont region of North Carolina invited people to a “rally and cross lighting” for “white people only” on May 26 in the town of Harmony in Iredell County. Opponents drawn from a recent campaign against the May 2012 ballot referendum to limit marriage to a man and a woman, along with immigrant rights activists from the Dreamers movement, mustered about 25 people for a couple hours to hold a rain-drenched “Hatred Not Welcome Here” counter-rally in Harmony, but the Klan met on private property and remained invisible to outsiders.

Barker’s group wouldn’t make much of a national impression until the next year, when they went to Memphis, Tenn. to protest the city’s decision to remove the name of Nathan Bedford Forrest, a former Confederate officer and the first national Klan leader, from a local park.

A post on the Loyal White Knights’ website reflects how the group used the Memphis protest to assert primacy as the most extreme and aggressive group in the Klan universe.

“We do not hide behind a mask,” reads the post, which is presumably written by Barker. “While all the other Klans hid in a field with their hands out scared of street action, we were at the front lines wanting a fight. I myself reached out to the imperial wizards asking to stand for our first wizard Nathan Forrest. They all said they were scared and we would be in their prayers. They truthfully should throw their robes into the fire and walk away with their tails between their legs.”

While the Loyal White Knights assert that they had 150 members at the protest, a report by the Southern Poverty Law Center — which monitors extremist groups — estimated that the number of all white supremacists at the protest totaled only 60, while more than 1,000 anti-racists came out to oppose the Klan.

©

©

Whatever the group’s propensity for self-aggrandizement and exaggeration, the razzle-dazzle-ready-for-battle image projected by the Loyal White Knights appeared to pay dividends. The Southern Poverty Law Center reported that the group grew from 16 klaverns — local chapters — in 2012 to 52 in 2013, making it the largest in the country, challenged only by the rival Traditionalist American Knights in Missouri. And judging by flier drops, which are often coordinated to happen simultaneously in different cities around the country through regular national conference calls, the Southern Poverty Law Center judged the Loyal White Knights to be the most visible Klan group in the country.

“They Loyal White Knights is the largest, most extremist Klan group in the country,” said Nate Thayer, a veteran journalist. Renowned for interviewing Cambodian dictator Pol Pot shortly before his death, Thayer has been tracking white supremacist groups for the past two years.

“They are a serious group with serious members,” Thayer said of the Loyal White Knights. “They attract the most extremist and unstable types of people in the white nationalist movement. Of the people who flock to white nationalism, their membership is disproportionately filled with people who are a real problem…. There’s a lot of meth-heads and people who are still pissed off at their mothers. These are people with long criminal histories.”

The Loyal White Knights group has periodically joined forces with the neo-Nazi National Socialist Movement at the most extreme end of the hard-right spectrum since 2012, but the Detroit-based National Socialist Movement distanced itself from the Loyal White Knights last year. When the National Socialist Movement joined with the Traditionalist Worker Party for a rally in Pikeville, Ky. on April 29 as part of an effort to form a National Front to organize white working people frustrated by globalization and opioid addiction, the Loyal White Knights were not included in the new coalition.

As a virulently white separatist, anti-Semitic and homophobic organization, the Loyal White Knights has positioned itself at the crux of almost every major flashpoint of racial tension in the United States over the past five years, focusing on Mexican immigration in 2014, rallying on the steps of the South Carolina State House in July 2015 in the wake of the murder of nine black parishioners at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church by Dylann Roof, and clashing with counter-protesters in southern California during the presidential primary in February 2016.

In a 2014 interview with Triad City Beat, Imperial Wizard Chris Barker described the situation on the United States’ southern border as a “land war.” (At the time he identified himself as Grand Dragon Robert Jones — a pseudonym likely inspired by another Robert Jones, who organized one the largest statewide Klan networks in the country in North Carolina from 1963 to 1969.

“I think we should have our troops there with a shoot-to-kill policy,” Barker said. “These people are obviously not getting the picture.”

In that interview, he advocated for a race war.

“We want to see America stay for Americans,” he said. “You can’t put too many races together on one continent. It’s like the melting pot has soured, and it’s about to explode. We’re going to see a racial war; a lot of us pray for it. We would love to see another civil war, and if it was to happen we believe we would win.”

III.

The Caswell County Courthouse, a squat, utilitarian building near the main highway in Yanceyville — about 40 miles northeast of Greensboro — houses the case files for Imperial Wizard Chris Barker and Grand Dragon William Hagen’s pending charges related to the attempted murder of their fellow Klansmen Richard Dillon. Barker, who was released from jail on Feb. 14 after posting a $75,000 bond, is due back in court on June 26. Hagen’s next court date is on the same day, but he’s already in jail awaiting sentencing in Orange County, Calif. for a conviction related to the 2015 beating of a homeless man outside of a bar, according to a report in the Orange County Register.

Meanwhile, in Caswell County, the justice system has experienced serious challenges. The combined Person/Caswell and Rockingham County district attorney offices have been under investigation since last July for possible theft of state funds related to a scheme in which the two district attorneys hired each others’ wives, according to reporting by the News & Record. Rockingham County District Attorney Craig Blitzer resigned on March 10, but Wallace Bradsher, his counterpart in Person and Caswell counties, has resisted pressure to follow suit.

A couple blocks up the hill from the current court stands the old Caswell Courthouse, an ornate building that now houses county government. A historical marker outside the old courthouse references a colorful history that is likely familiar to Chris Barker: “Erected about 1861. Murder of JW Stephens here in 1870 led to martial law and Kirk-Holden ‘War.’”

Caswell, along with Alamance, its neighbor to the south, held a reputation as being Ku Klux Klan strongholds in the years after the Civil War as the secretive paramilitary group attempted to terrorize free blacks into submission while also intimidating the white radical Republicans who upheld the cause of interracial cooperation. In 1870, Gov. William Woods Holden declared the two counties to be in a state of insurrection when local leaders refused to control violence against blacks and white sympathizers, according to a June 2006 article in This Month in North Carolina. Holden declared martial law in Alamance on March 7, 1870, a couple weeks after white vigilantes lynched Wyatt Outlaw, a black member of the Graham Town Commission.

State Sen. John W. Stephens, a member of the Republican Party and Union League, was lured into a secure room in the Caswell Courthouse while a meeting of the white supremacist Democratic Party was taking place upstairs on May 21. There he found eight white Ku Klux Klan members and a black man. According to an 1873 account in the New York Times, after Stephens refused to renounce his Republican principles while asserting that his black constituents depended on him, he “was thrown down on a table, two of the Kuklux holding his arms. The rope was ordered to be drawn tighter, and the negro was ordered to get a bucket to catch the blood. This done, one of the crowd severed the jugular vein, the negro caught the blood in the bucket, and Stephens was dead. His body was laid on a pile of wood in the room, and the murderers went upstairs, took part in the meeting, and stamped and applauded Democratic speeches.”

As a result, Gov. Holden declared martial law in Caswell on July 8. According to Tomberlin’s account, General George W. Kirk led a state militia into Alamance and Caswell counties, and arrested more than 100 people, who were jailed in Caswell County to await trial before a special military court. Yet the balance of power was to be reversed in short order: Under President Ulysses Grant, the federal government declined to support Gov. Holden’s actions, and the prisoners were released in late August. The white supremacist backlash against Holden would lead to his impeachment in December and removal from office early in 1871.

IV.

At the time Imperial Wizard Chris Barker allegedly participated in the brutal assault against Richard Dillon, he was on supervised release after pleading guilty to federal charges of possession of a firearm by a felon. Among the conditions of Barker’s release, his federal sentence stipulated that he not commit another crime and that he refrain from excessive alcohol use. Additionally, the conditions required that Barker “not associate or be in the company of any gang member/security threat group member, including but not limited to the Ku Klux Klan.

“The defendant shall not frequent any locations where gangs/security threat groups congregate or meet,” it went on to say. “The defendant shall not wear, display, use or possess any clothing or accessories which has any gang or security threat group significance.”

Barker’s two-month sentence after pleading guilty to the charge was lenient by almost any standard, to begin with. In comparison, Randolph Kilfoil, a member of the North Carolina Latin Kings, received a sentence of seven years in federal prison after pleading guilty to possession of a firearm by a felon in the same court in 2010.

When Barker was released from his two-month stint in custody in October 2013, he seemed to routinely violate the terms of his supervised release without consequence. The prohibition against associating with the Klan posed a particular problem.

James W. Long, Chris Barker’s federal probation officer, met with him and his wife, Amanda, at their home in Eden, where they lived at the time, on Oct. 30, three days after his release.

“Mr. Barker reported that he understood the conditions of his supervision and advised that his wife, Amanda Barker, remained an active member of the Loyal White Knights of the KKK which has presented to be a challenge for our office and Mr. Barker’s supervision,” Long wrote in a report to the court.

The probation office investigated numerous allegations throughout Barker’s supervision that he was an active advocate and spokesman for the Loyal White Knights through media interviews. One was an August 2014 story on the Al-Jazeera news website involving a reporter who met two KKK members wearing robes and hoods at the post office in Pelham. The reporter followed the two Klansmen to a location beside a pond and a tobacco field.

“In the interview the lead KKK member expressed his displeasure with the immigration of individuals from other countries to the United States,” Long reported. “He voiced that if some of the illegal aliens were killed that it may send a message to others.

“It should be noted that the vehicle which appeared in the video appeared to be a Chevrolet sedan, which was dark blue in color with a Tri City license tag on the front bumper. The vehicle is a car known to have belonged to Mr. Barker at that time. The probation officer identified Mr. Barker as the KKK member in the video by the sound of his voice and by a circular tattoo which appears on his wrist.”

In August 2015, a state highway patrolman arrested Barker twice in one day before noon for driving while impaired, along with an open container violation.

“Mr. Barker reported on the day of his arrest he and his wife had been drinking with friends at his residence,” Long wrote. “Mr. Barker reported that he was driving to the ABC Store to purchase more alcohol when he was stopped by law enforcement. Mr. Barker reported that he had a bottle of alcohol that he tried to drink as the officer approached his truck. Mr. Barker reported that he was arrested and taken to the Caswell County Jail. Mr. Barker was offered the opportunity to attend substance abuse treatment, but showed no motivation to attend.”

The state charges wound up getting dropped because the state highway patrolman resigned from his position due to his own driving while impaired charge, according to federal court records.

After a meeting with the Barkers at the McDonald’s in Yanceyville in February 2016, Long also observed a bumper sticker displaying the KKK symbol and the words “100% American” on the rear window of the couple’s Dodge Durango. In yet another violation in March of that year, Long ascertained that the Barkers visited a printer in Yanceyville to have a Loyal White Knights banner made. Chris Barker reportedly produced a Loyal White Knights business card and asked the store associate to duplicate the image on the banner.

Long said when confronted with accusations about his ongoing involvement in the Loyal White Knights, Barker typically denied it or passed responsibility to his wife.

“For example, when confronted with the Al-Jazeera interview in August of 2014, Mr. Barker denied being the person interviewed, but did not deny that their personal vehicle was seen in the video,” Long wrote. “Mr. Barker stated that his wife allowed other people to use their car. As Amanda Barker is known to be active with the KKK, this creates difficulties with supervising Mr. Barker. We’ve not enforced the association condition with his wife as they reside together with their two children.”

While Long argued that Barker was in violation of the conditions of his supervised release, he noted to the court that the probation office found itself at odds with federal prosecutors.

“We’ve had ongoing discussions with the Assistant United States Attorney in this case and have had some difference of opinion regarding the interpretation of the special condition wording and what is a violation,” Long wrote.

On June 23, US Magistrate Patrick Auld found probable cause to support the revocation of Barker’s probation.

“The defendant’s family acknowledged during his original sentencing that substance abuse and negative associations have caused the defendant problems throughout his life,” Auld wrote. “Further, the defendant has three prior convictions for driving under the influence, and while on supervised release, he evidently again drove intoxicated, thus endangering the community. Moreover, the record reveals that the defendant has re-associated himself with gang members/security threat group members, and worn, displayed, used and/or possessed clothing and accessories signifying those associations. In sum, when the defendant abuses substances and pursues affiliation with security threat groups, he can quickly become involved in behavior that poses a danger to the community. Under these circumstances, the court lacks a clear and convincing basis to conclude that, if released, the defendant would not pose a danger to the community in the form of substance abuse and negative associations.”

Based on Auld’s finding, US District Court Judge James A. Beaty ordered that Barker to receive three months of home detention and that his supervised release, originally set to expire on Oct. 26, 2016, be extended an additional year.

Up to the time of the alleged assault on Richard Dillon, Long reported that Barker was making good progress.

Court documents acknowledge that Barker violated two separate conditions — not committing a crime and not associating with the Ku Klux Klan — through his involvement in Dillon’s stabbing. Yet in a remarkable piece of legal gymnastics, Barker’s probation officer argued that his probation should be retroactively terminated so that the Dec. 3 violations wouldn’t apply. Long wrote that prior to the original expiration date on Oct. 26, he had realized that Barker had already served the maximum amount of supervised release under federal statute. Judge James A. Beaty agreed to the recommendation despite the fact that, as he had written in his Aug. 25, 2016 order, “The court considered the applicable sentencing guidelines policy range, along with the nature and circumstances of the offense, the history and characteristics of the defendant, any pertinent policy statements issued by the sentencing commission, the need to provide restitution to victims of the offense, and Congress’ objective in avoiding sentencing disparities.”

The federal courts’ apparent reluctance to bring the hammer down on Chris Barker makes a little more sense in light of an allegation published by journalist Nate Thayer in July 2015, on the eve of the Loyal White Knights’ rally on the steps of the South Carolina State House, that Barker is an undercover agent for the FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force.

In the late spring or early summer of 2012, the FBI learned of a plot by Glendon Scott Crawford, an industrial mechanic at General Electric’s Schenectady plant and a self-identified member of the United Northern & Southern Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in upstate New York, to build a death-ray-type weapon of mass destruction to kill Muslims.

“The essence of Crawford’s scheme is the creation of a mobile, remotely operated, radiation-emitting device capable of killing human targets silently and from a distance with lethal doses of radiation,” FBI Special Agent Jeffrey Kent wrote in a July 2013 affidavit. “A central feature of Crawford’s weaponized radiation device is the target(s), and those around them, would not immediately be aware that they had absorbed lethal doses of radiation, and the harmful effects of that radiation would not become apparent until days after the exposure.”

Kent wrote that through monitoring conversations between Crawford and a confidential human source and undercover employee, “agents have heard Crawford state that he harbors animosity towards individuals and groups that he perceives as hostile to the interests of the United States — individuals he refers to as ‘medical waste.’ Crawford has specifically identified Muslims as belonging to this group.”

After unsuccessfully soliciting assistance to build the death ray, Crawford eventually found two separate groups with the apparent means and ability to obtain the type of X-ray systems he needed to make his scheme operational. Both groups, as Kent noted, were controlled by law enforcement.

In late July 2012, Crawford prepared to undergo surgery. He was concerned that he might not survive, and wanted to make sure his scheme went forward. A July 27 email message from Crawford to an undercover FBI employee, although redacted, leaves little doubt about who he thought he could count on to execute the plan. “Further, once you have my computer and phone, get ahold of ————, of the loyal white knights, 1-336-xxx-xxxx. To make certain this happens, I will have a friend names [sic] — working my end to reach you and get this stuff to you. The knights may have the resources to invest and bring the project to fulfillment. That is, if you wish to continue. If not, let me know and I will make arrangements for others to shoulder your load in this.”

Three days later, on July 30, Barker was indicted on two counts of possession of a firearm by a felon. Thayer alleges that in August he agreed to act as an informant for the FBI Joint Terrorism Task Force and assist in making the case against Crawford.

©

©

©

The larger question is, why are you advertising for these people?

We are not “advertising for” the Ku Klux Klan, anymore than we advertise for the Democratic Party, Black Lives Matter or the Greensboro Police Department when we write about them. The Klan is a social force that appeals to a small segment of the population and to an extent shapes our shared reality. Readers deserve to know what they’re doing and how law enforcement is responding to them.

With the revelation that the Barkers are FBI informants and the company they keep, I am surprised they are still alive. I am more surprised that FBI support allows the Loyal White Knights of the KKK to operate with impunity and blanket immunity from prosecution. Repulsive.