Para leer este reporte en Español, seleccione Español del menú en la parte derecha de esta página.

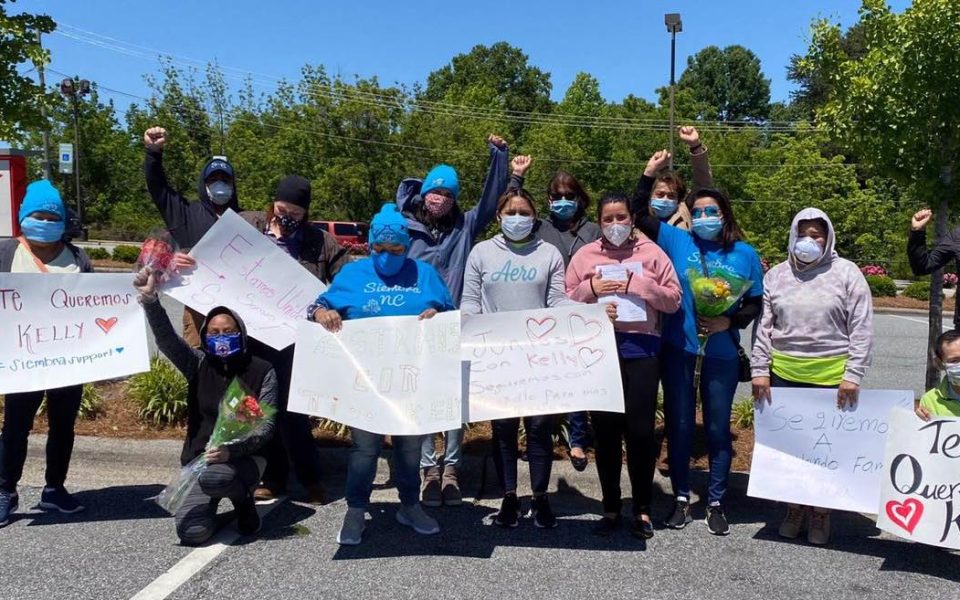

Featured photo: Members of Siembra NC at a recent rally (courtesy photo)

A majority of the state’s Latinx communities are having trouble paying rent and are struggling financially due to job loss in the face of the pandemic, according to a recent survey.

From May 3 to May 6, Siembra NC, a grassroots organization that advocates for Latinx communities, conducted a text message survey with 309 participants from Guilford, Forsyth, Alamance, Mecklenburg, Wake, Durham, Orange, Catawba, Chatham, Davidson and Randolph counties. Question topics ranged from employment, federal assistance to housing and other needs. 154 of the respondents said they live in the Triad. The data showed that 69 percent of respondents live in households where at least one person has lost work and that 70 percent of respondents need help paying rent, which was their greatest concern.

“As you are able to see, we’re talking about high percentages of folks who are not able to pay rent already,” said Kelly Morales, a rapid-response coordinator for Siembra NC. “People who have been owing for the past two months. The concern is that when June 1 comes, it’s clear that these families are in a lot of risk of eviction and facing homelessness.”

In early March and April, state Supreme Court Chief Justice Cheri Beasley issued orders temporarily pausing state court proceedings, including evictions, until June 1. Following the chief justice’s orders, sheriffs across the state, including in Forsyth and Guilford Counties, put a moratorium on executing eviction notices until June 1, but in the past week, both sheriffs’ offices stated that they would resume evictions — on May 29 in Guilford County and June 1 in Forsyth.

That leaves several Latinx families, whose wages have been slashed due to the pandemic, in a precarious situation, according to Morales.

“We know that there is a pause in the courts right now, but we also know that a lot of different neighborhoods and trailer-park communities and apartment complexes have continued to send out messaging that rent is still due and bills are still due and that starting on June 1, they are going to start evicting people,” she said.

Delia Padilla, a Mexican immigrant and advocate for Siembra NC, is one such individual.

Prior to the pandemic, Padilla was working three days a week at an Outback Steakhouse as a line cook, and as a house cleaner for another three days. At the end February, Padilla’s hours at Outback started to get cut and by March, she was laid off. Now, she’s working one or two days a week cleaning houses to make ends meet. Her husband, who works as an A/C installation contractor, has also seen a decrease in work. Prior to the pandemic, he was working six days a week but now only works four.

Even though her family is generating much less income, her landlord at the trailer park where she lives has said that they are waiving late fees but that if rent payments, which are due on the first of every month, are not received by the 12th, they would be sending out eviction notices to tenants. Siembra’s survey found that 45 percent of respondents were not able to pay their full rent for the month of May.

“I think I have the same concerns that any other family might have if they lost 40 to 50 percent of their income,” Padilla said during a phone interview through a translator. “It’s been hard to pay the rent, the bills.”

Fortunately, unlike some of her Latinx community members, Padilla immigrated to the United States 23 years ago and resides here with a green card. As a result, she is receiving a federal stimulus check. However, many in the Latinx community are undocumented and do not have Social Security numbers, which means they won’t receive funds from the government.

In fact, only 13 percent of the survey respondents said that they had a person in the home who qualified for the stimulus check.

“They have no kind of relief,” Morales said. “These are the folks that we are extra concerned about.”

In addition to financial struggles, the survey found that 48 percent of respondents did not know how to access food assistance in their communities.

“Even with good communication around food banks and resources for food access, we still had a high percentage of folks not reaching out to these resources or even knowing that they exist,” Morales said.

She attributes the lack of access to the issue of language barrier. Morales said not speaking English as a first language, as is the case for many immigrant and refugee communities, puts them at a disadvantage for many resources.

“Even at the beginning when we had the stay-at-home orders, we had great information being published but none of it was in the language of our community members,” she said. “We need to have information out there in the languages that folks are speaking.”

Padilla said that she has been getting most of her COVID-19 related information through Siembra or Univision, the Spanish-language TV network.

Websites like the state DHHS, which posts numbers of COVID-19 cases and other data points daily, often don’t have a Spanish version of their site, or when they do, they don’t translate the page properly or fully. In the case of the state’s DHHS website, the page that shows the number of current COVID-19 cases can be translated into different languages like Spanish using a Google Translator tool at the top right of the page, but the graphs and the accompanying information that describe the graphs do not. To explain this, the DHHS has a translator disclaimer page on its site explaining that the “translations should not be considered exact and used only as an approximation of the original English language content.”

At the county level, Siembra Director Andrew Garcés recently pointed out in a series of emails to Guilford County Public Health Director Iulia Vann the lack of data showing COVID-19 cases for Hispanics. The website has graphs for race which includes Asian, black, Native American, other and white, but does not show data for ethnicity, which would include Hispanic.

In a phone call, Vann argued that the ethnicity data wasn’t being posted on the county’s website because staff was mirroring race data from the state’s COVID-19 page, but the state DHHS clearly breaks down the data for ethnicity under the bar graphs for race. Vann said her staff will soon start posting the ethnicity data on the county website as well.

According to the state’s data, 32 percent of cases have been Hispanic even though the state’s Hispanic population is only 9.6 percent based on the US Census. In Guilford County, as of Monday, 109 out of 874 cases, or 12.5 percent of cases were Hispanic, but Hispanic status was unknown or missing for about a third of all cases according to data provided to Triad City Beat by Garcés. The Hispanic population in Guilford is 8.2 percent. In Forsyth, a whopping 54.3 percent of cases were Hispanic according to county data, even though Hispanic individuals only make up 13 percent of the county’s population.

Nationwide CDC data shows that the Latinx population is being disproportionately affected by the coronavirus in both deaths and collateral stress like job loss, and are second only to African Americans in many states, including North Carolina.

In New York City, Latinx individuals had the second-highest rate of coronavirus deaths and nationwide, a Pew Research Center study found that Latinx individuals reported higher rates of layoffs or pay loss because of the pandemic, compared to the rest of the population.

In Guilford County, out of the 35 COVID-19-related deaths, one was a Hispanic individual, which amounts to .03 percent — according to death certificates provided by the county. State data shows that of the 702 total deaths due to COVID-19, only 5 percent were of Hispanic individuals.

While exact causes of higher deaths and infection rates cannot be pinpointed, researchers like Daniel López-Cevallos, professor of Latino and health equity studies at Oregon State University, attributed the trend in a recent New York Times article to issues that predate the pandemic like socioeconomic status, lower education levels, less access to health care and more employment in essential services. Understandably, he said that Latinx individuals with less support systems tend to do worse.

Respondents to Siembra’s survey said the biggest thing that can help them now is financial help for bills and rent payments. They also said they need help with their kids’ education and homework.

Padilla, who has three kids at home, said helping them with schoolwork has been one of the most challenging parts about the pandemic.

“It’s been really hard to support them,” she said. “They ask for help but the book is in English, the assignment is in English and they’re constantly inundated with tasks. They’ve lost motivation.”

To help members of the Latinx community during the pandemic, Siembra has been doing an ongoing donation drive to collect money for families in need.

“We need to listen to our community and see what they’re asking for,” Morales said. “It’s about allowing and recognizing that we don’t all have access to the same resources.”

To learn more about Siembra and its efforts to help the Latinx community, visit the organization’s website here.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply