Lonnie Holley’s mind is like a kaleidoscope.

With each new turn, a differing perspective emerges that’s just as vivid and complex as the last. It’s ever-changing; his art is the same way.

Holley’s new show, Somewhere in a Dream I Got Lost, which opened at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art on Dec. 13, showcases just a recent slice of his work and includes both sculptural and print pieces, as well as a sample of his music.

Late afternoon on the day of the exhibit’s opening, Holley sits in a corner of the gallery at a listening station in what looks like an IKEA chair, the kind that, without back legs, appears to float. He wears hues of black and multiple rings adorn his left hand while a pair of black-and-white American flag gloves hang from a scarf that’s draped around his neck. On his head sits a pair of headphones through which Holley listens to one of his songs, “I Woke Up in a Fucked-Up America.”

Cacophonous and varied, the instrumentals and Holley’s vocals punch through the speakers, carrying the lyrics like words in a sermon.

“I fell deeper, deeper, deeper in a dream,” belts Holley. “And I dreamed that I woke up in fucked-up America.”

Brass harmonies blare as sharp piano notes cut through Holley’s sing-shouting that sounds like spoken word. At times it’s hard to understand what he’s saying but the feeling is there; it’s one of deep pain and powerful sorrow.

In the gallery, dozens of Holley’s pieces speak to the same sentiment.

Displayed behind a clear, plastic box, a glass bottle with the word “Hood” embossed on it sits atop a pedestal. Filling it are dozens of rusty nuts and bolts and out of the neck emerges a long, heavy water faucet. Titled, “No Milk and Bad Water in the Hood,” the card next to the sculpture describes Holley’s process of creating the piece and how he initially tried to get the faucet to stand on its own in the milk bottle, to no avail. He then added the oxidized pieces of metal and found that they helped keep the pipe upright.

©

“I started thinking about all the metal and rust in the bottle and it made me think about Flint, Michigan,” Holley explains in the card description. “The idea just came to me that people in the ’hood don’t have milk to nourish their babies and the water is tainted. How many other places have their own problems that we won’t know about?”

While he’s known mostly for his music now, the 68-year-old artist has been creating visual art since the late 1970s. Taking hardships from his early life which included years in foster homes and some time in a juvenile labor camp in Alabama, Holley found his calling after carving tombstones for his sister’s children out of sandstone he found at a nearby foundry. Like these first sculptures, his work is predominantly made of found objects that he collects from dumps or roadsides or forgotten creeks and ditches. Trash literally becomes treasure, his medium and his muse.

“I’ve always been different,” Holley says as he walks around the gallery. “I couldn’t afford brand-new materials. A lot of artists can’t afford new materials but that doesn’t make them less of an artist. I use objects that people have thrown away.”

And while the objects he uses may seem simple and commonplace to many, to Holley, they carry layers of meaning. Ordinary objects are rearranged and transformed to tell profound stories.

“He is insanely smart,” says Wendy Earle, the curator of contemporary art at SECCA. “He’s making connections that the rest of just can’t make. He’s looking at things holistically.”

Like “No Milk and Bad Water in the Hood,” many of the pieces in the show reflect themes of neglect and racism, as well as motifs of discrimination and subjugation. A golden eagle trapped in a birdcage symbolizes captivity while a mannequin with a spigot and a bucket stuck in its chest serves as a metaphor for how people can become drained by events in their lives like a tree tapped for its sap.

©

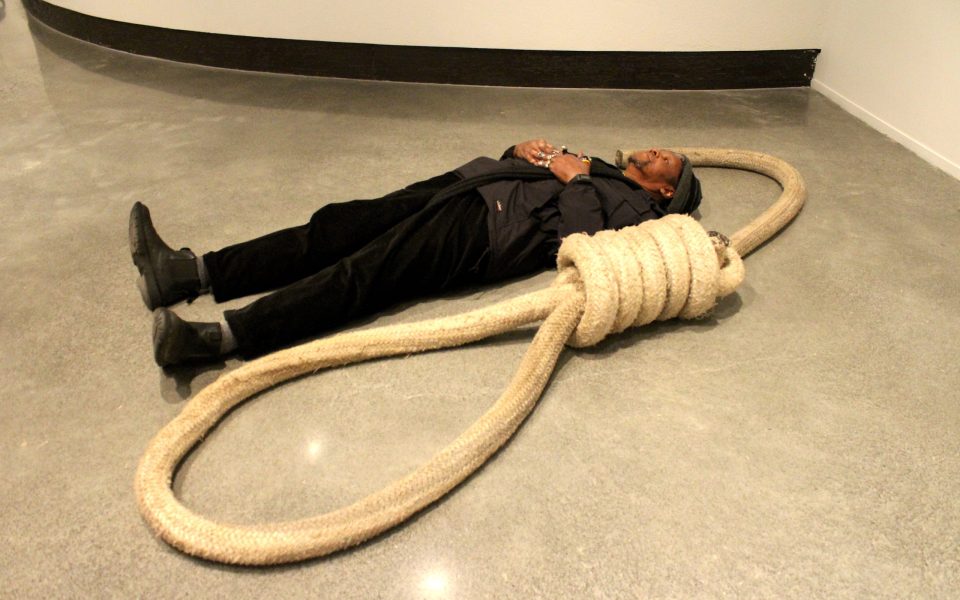

Towards the beginning of the show, at the bottom of the stairs, lays a giant piece of rope that’s been tied into a noose.

Holley walks up to it and lays down at the end of the rope so that his body becomes an extension of it. The looped portion that lays next to him measures about as long as he is tall. It was originally a tow-boat rope, titled “Hung.” The card explains how ropes have been used for good and necessary purposes throughout history but how when used by the wrong people, they can and have, been used for evil.

Even the way Holley speaks has a prophetic quality to it. His words meld together and with every added word — like a bartender making a cocktail — he adds new meaning and depth of flavor to his sentences.

“As humans, as artists, we need to talk about the aftermath of our disasters,” he says.

Looking around the exhibit, it’s hard to imagine that most of the pieces were made in the last two years. At almost 70-years-old, it seems Holley has no intentions of stopping any time soon. His 2018 album, MITH, has been critically acclaimed while his recent short film, “I Snuck Off the Slave Ship,” was recently accepted into the 2019 Sundance Film Festival.

“A lot of my pieces are about self-lubrication, about fueling yourself,” Holley says. “We learn more than just in school; every second of life is an experience.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply