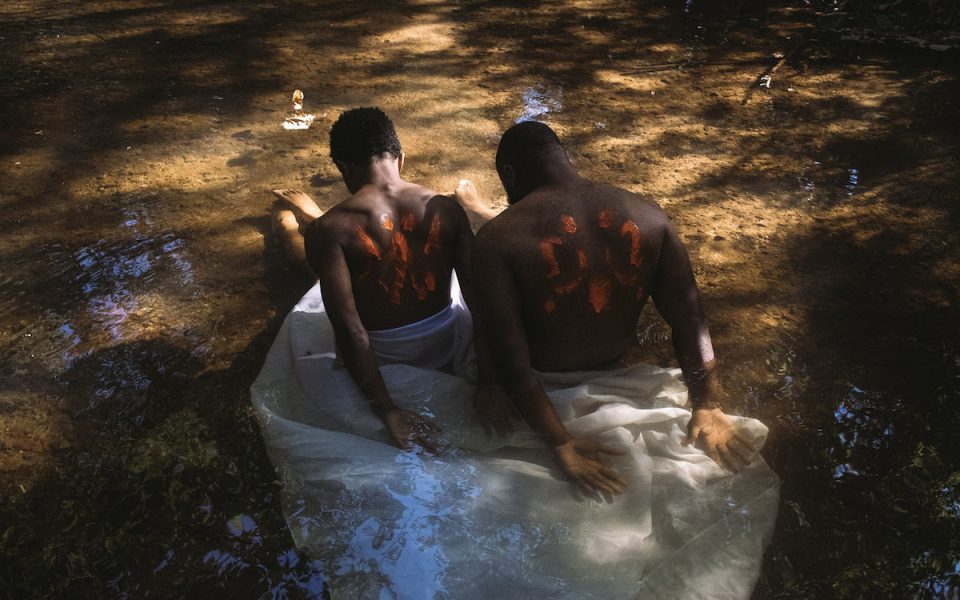

Featured photo: “…from baptisms” (photo by Ashley Johnson)

Is it blood? Are they symbols? What are they saying? What do they mean?

These are the questions that arise when looking at Ashley Johnson’s latest series of work, titled Mark Yourself Safe. In the group of moody photographs that depict the backs of Black men, Johnson paints abstract, Rorschach-inspired patterns onto their bodies, a representation of the viewer’s fear of the Black male.

Johnson, who is a multidisciplinary artist working out of Winston-Salem, will be showing her new series at SECCA as part of the Southern Idioms project starting Jan. 16. The artist says that the images came to her in a dream she had a few years ago in which she was visiting a group home where a bunch of boys broke free and painted the vibrant shapes on their backs.

“This fluorescent orange is bright the way caution and construction signs are bright, making it a very necessary figure in the work,” Johnson responds in an email. “Two things can happen, either the orange shapes beg your attention or the man, and then we do what all audiences do with art — find meaning or reason.”

Johnson responds to the fact that some viewers may make connections of the painted backs to the history of slavery by turning that interpretation back on the viewer and society at large.

“It signals that there is a very siloed way in which we can approach or interpret Black men not just in art, but in our daily lives,” Johnson says. “And much of that centers around fear. If Black men are not useful, then our default is that we have something to be afraid of.”

Johnson says that using the Rorschach-inspired inkblots invites viewers to contemplate what they are afraid of, and why, when it comes to the Black male body.

“Black skin is the same way,” she writes. “We’ve been conditioned to project our judgement onto Black skin as a space to make determinations on our safety. In this way, we use the size and depth of Black skin as a barometer for fear.”

For models, Johnson chose a variety of Black males including her brother, who works at a local meat counter. In a description of the work on her website, Johnson writes that despite his employment at the shop, it doesn’t stop women from clutching their purses when near him nor does it combat complaints about him wearing his hat backwards. All of the individuals in the images for the series have their backs turned, their faces cast away from viewers’ gazes.

In one striking image, Johnson captures her brother leaning away from the viewer as a pit bull stands proudly between his legs. Her brother reaches down to hold his dog in place and to his right, a laundry line pole can be seen. His pants sag slightly below his hips, exposing his grey boxers. The bright orange paint contradicts vibrantly with his deep, dark skin.

“When you focus on this Black man…standing in a neighborhood you wouldn’t dare step foot in, it’s not a question of whether or not you are afraid, because you are,” Johnson writes. “The question is, of what?”

In another image, a pair of Black men sit in a body of water, their heads hanging low, a white sheet of fabric flowing between them. Their hands are behind their backs and sunlight from above dapples gently onto their backs, bringing further attention to the shapes that mark their bodies. Johnson says that excluding faces is a constant thread throughout her work.

“I like for audiences to draw conclusions without the help of the subject’s expression,” she says. “It inadvertently serves the point of the work that you don’t even need a fact to draw a fear-based conclusion or to have a fear-based conclusion before approaching the work.”

And while the work is set to be shown at the museum soon and is already up on her website, Johnsons says that she took a long time to display these pieces because she felt that they weren’t quite done. However, she says recent events have made it necessary to show them now.

“When trying to figure out how to contribute my voice to the movement, I thought, even unfinished it needed to see light,” Johnson says. “At the root of any discomfort is fear.”

The images may draw on Johnson’s personal experiences as a Black woman and use images of family and friends, but Johnson says that the series is for everyone, not just white folks who are contemplating their fear of Blackness.

“This work is for everyone to address bias,” she says. “Deeply embedded, racially motivated bias that enables fear and how that fear impacts our decisions — the people we follow on social media, the neighborhoods we live in, the feelings of danger on certain sides of town…. My contribution to last year’s uprisings was to hold up a really large mirror.”

Mark Yourself Safe will be on display the SECCA from Jan. 16 through Feb. 14. Visit secca.org or hiaj.co for more information.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply