Marsha P. Johnson, a transgender activist during the late ’60s and ’70s, lived for a time in a Hoboken, NJ high-rise apartment with a man named Randolfe Wicker. He largely tolerated her odd behavior but asked her not to wear drag when coming and going from the apartment.

Instead, she wore bulky clothing, following Wicker’s request, and got on the train to New York. Her dress would peek out of the bottom of her leather jacket and by the time she got to Christopher Street in Manhattan, she’d take off the layers to reveal her authentic self.

Guilford Green Foundation and LGBTQ Center hosted a screening of Pay it No Mind: The Life and Times of Marsha P. Johnson, a feature documentary on Johnson’s life in New York as an activist, at the International Civil Rights Center and Museum in Greensboro. Afterwards, a panel of local activists held a discussion on the film and the LGBTQ+ rights movement.

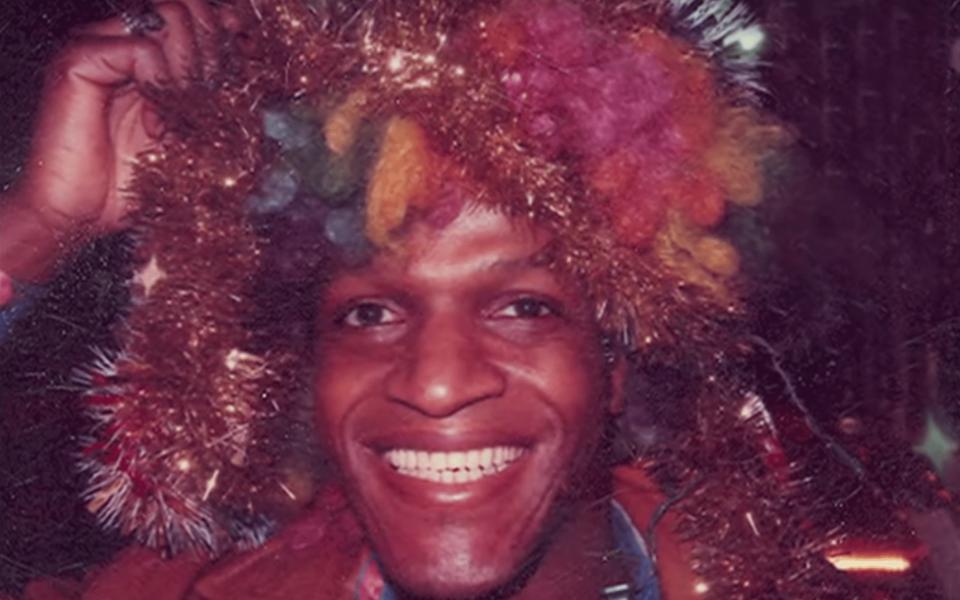

“[Johnson] had a glow about her,” said Roselynn Arroin, a trans woman of color who spoke as a panelist at the event. “Something others don’t understand. Her glow gave her strength and, ultimately, gave her respect in the LGBTQ+ community.” Johnson was like a lighthouse that stood tall in the ceaseless tempest of bigotry towards queer and trans folks. She’s inspired people like Arroin to become activists for the LGBTQ+ movement.

“There was a corporate man who told me that I could sell myself to him in secret but that I couldn’t have a job at his company,” said Arroin, talking about her struggles to live genuinely with her gender identity. “Being at the bottom for so long — it challenged me to become an indestructible woman who built herself from the ground up and when white corporate America said, ‘No,’ she would say, ‘Yes.’”

Arroin first came to Greensboro in 2010. She now works in home healthcare and takes care of two dogs with her boyfriend. For a while, though, things weren’t so idyllic.

“I was homeless,” she said. “I had to depend on sex work…. I didn’t have [things] together was because I wanted to be my authentic self. The doors closed in my face every time, even though I had credentials and a degree. The only way I could survive was to sell my body.”

Johnson moved to New York from Elizabeth, NJ after graduating from high school. Her life at home wasn’t pleasant; her mother knew nothing of the LGBTQ+ community and referred to homosexuals as “lower than dogs.” In 1970, Johnson helped to create the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionary House with prominent activist Sylvia Rivera. The “house” functioned as a shelter for transgender sex workers and other outcast LGBTQ+ youth. Nothing like it had existed before in the United States. She’s famously cited as one of the instigators of the Stonewall rebellion in 1969, which celebrated its 50th anniversary this year, where LGBTQ+ community members protested against the New York law-enforcement who policed their bodies.

“I was one of the queens [who] helped feed the queens that were hungry,” said Johnson in 1992 during her final interview. She went missing four days later and the NYPD eventually found her body in the Hudson River.

Johnson and Arroin share many things in common. They each struggled with their homelives, moved out of their parent’s place with little to no money and worked as sex workers. The most significant similarity, though, is the role they played in the activist circles of their respective communities.

“It’s gonna be the first year that we’re marching down 5th Avenue,” said Johnson in her 1992 interview, referring New York’s gay pride parade for that year. “I think that as long as there are people with AIDS and as long as gay people don’t have their rights, all across America, there’s no reason for celebration…. ’cause you never completely have your rights until [we] all have your rights.”

Arroin now carries the same torch that Johnson did all those years ago.

“As an activist, I’ve been involved in protests and lobbying,” said Arroin. “I’ve gone down to State Street in Raleigh and I’ve lobbied in the legislature’s office. I’ve talked to a lot of legislators about Medicaid expansion in North Carolina so that it would include people living with HIV or AIDS.”

Before Arroin got into lobbying, she had to get her life in order.

“I [once] went to Chemistry and ran into a man named Drew Wofford, he’s now the owner there, and we talked for a while.” she said.

Wofford noticed Arroin’s struggle. She had just moved to an apartment but she had no income. Wofford payed Arroin to mow his grass and he later hired her to work the front door at the club.

Arroin went back to school for nursing while she worked at Chemistry. The club was a safe haven, a place where her identity felt welcomed. In this environment, Arroin didn’t have to hide her dress under a leather jacket — she could express herself to the fullest extent. The cultural translucence she suffered for so long lifted like a veil and she could finally achieve a successful life.

“Our movement began before Stonewall,” said Rev. Liam Hooper, one of the other panelists. Hooper founded Ministries Beyond Welcome, an organization that aims to improve the lives of trans and queer people through public education, advocacy, activism and general support activities. “There were bars burning; people died in them. The oppression queer folks experienced at that time happened every weekend…. And who stood up? The people who were least protected and least able…. Black trans women, Latinx trans women…. Until we, the queer community, stand up collectively and those of us with the privilege of white skin, or regular employment, are willing to put the same amount of work [as] the most marginalized groups put in, then we’ll never get free.”

Pay It No Mind: The Life and Times of Marsha P. Johnson is available to stream on YouTube.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply