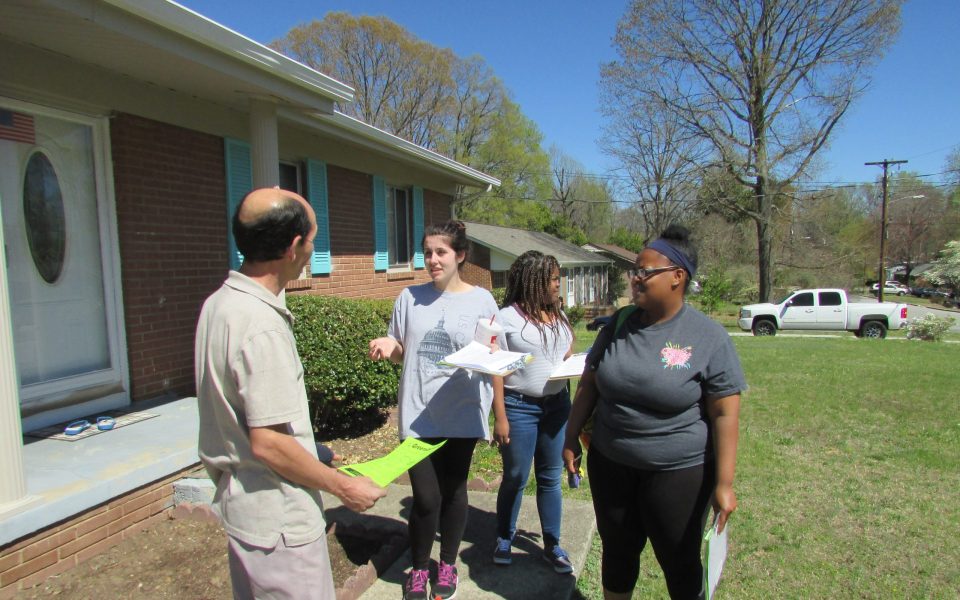

Student volunteers from UNCG are canvassing neighborhoods in Greensboro’s five city council districts to encourage residents to attend idea collection sessions for the city’s participatory budgeting project. Organizers are trying to increase participation in the midst of criticism from Councilman Tony Wilkins.

Tony Wilkins, a Republican who represents suburban District 5 on Greensboro City Council, is one of the most vocal opponents of participatory budgeting, a process that carves out $500,000 from the city’s multi-milliondollar annual budget and allows residents 14 years and older to vote directly on how the money is spent.

As the city kicked off its second year of participatory budgeting, student volunteers from Spoma Jovanovic’s communications and communities class at UNCG combed through Wilkins’ district and encouraged residents to bring proposals for improving their neighborhoods to a series of idea collection sessions. A group of budget delegates will vet the ideas over the summer, and in November residents will have the opportunity to vote on which projects they want to fund.

Wilkins was on the losing side of a closely divided 5-4 vote to implement participatory budgeting in 2014, and he said the first year of the program gave “him plenty of ammunition to support why I oppose it.” Particularly, he objected to the choice made by residents of District 5 to allocate $20,000 for two game tables to be installed at Griffin Recreation Center and Hester Park this spring.

“We live in the highest taxed city in ratio to the size of our city in the second hungriest [metropolitan statistical area] in the country,” Wilkins said in a recent interview, “and to spend $20,000 on game tables was ludicrous in my opinion.”

Wilkins said city staff was able to procure the gaming tables at a lower cost and complete the project for only $10,000. Last month, he persuaded his fellow council members to vote unanimously to reallocate the remaining $10,000 to Out of the Garden Project, which provides food each weekend to the families of K-12 students and operates mobile markets in under-served areas across Greensboro.

Wilkins said he hoped the volunteers’ efforts to increase the number of residents who weigh in would be successful.

“If we have more than what we had last year — 71 out of 50,000 participating, that would certainly be a plus,” he said.

The actual number of District 5 residents who voted on projects last year is 139, according to figures provided by Karen Kixmiller, the lead staffer in the city’s budget office on participatory budgeting. That compares to 323 people in District 4, 303 people in District 2 and 229 people in District 1. District 3 had the lowest participation, with 128 people voting.

The numbers across the five districts are miniscule when considering that the population of each of the five districts is about 54,000 in a city of 269,666 people. Participation in the most recent city council elections in 2015 exceeded voting in participatory budgeting by a factor of about 10, ranging from a low of 2,144 in District 5 where Wilkins ran unopposed to a high of 5,493 in District 3, which featured a competitive election between Justin Outling and Kurt Collins.

Valerie Warren, a consultant who is working under contract as a community engagement coordinator, said she doesn’t think the comparison is fair.

“There’s no Democratic Party or Republican Party machine that’s supporting the effort,” she said. “We don’t have the funds of a C(4) [organization] to pour into a campaign.”

Both Warren and Wayne Abraham, a member of the Participatory Budgeting Steering Committee, pointed to findings in a report by Spoma Jovanovic and Vincent Russell at UNCG indicating the 164 people who participated in the participatory budgeting neighborhood assemblies in 2015 compared favorably to turnout for public input meetings for the city’s annual budget in prior years, which dropped from 114 in 2012 to 69 in 2015.

Abraham also noted that one of the goals of the steering committee is to empower people who don’t typically participate, and 80 percent of the people who showed up to contribute ideas, vet projects and vote on the final ballot said they had never engaged in the city budgeting process before. In that sense, he said, the process was successful.

Abraham said it’s difficult to compare participation in Greensboro with other cities that have undertaken participatory budgeting. The only other city in the United States with a citywide program is Vallejo, Calif., which instituted participatory budgeting through a special tax after the city emerged from bankruptcy — a seismic event that generated significant publicity.

“We’re unique in that we’re doing it in the South, we’re doing it citywide and we’re carving it out of the budget,” Abraham said. “Getting people’s attention isn’t easy.”

On a recent Saturday, six student volunteers from UNCG canvassed neighborhoods to talk to residents about participatory budgeting. They started in the morning near Morehead Elementary in District 4, and reconvened in the parking lot of the State Employees’ Credit Union on Holden Road to begin canvassing in District 5.

Before they had knocked on the first door, the volunteers had to run across four lanes of traffic on Holden Road to get to the Farmington Forest neighborhood near Smith High School.

“We don’t have a crosswalk,” Arissa Drayton groused.

“It’s a project for participatory budgeting,” enthused Megan Montgomery.

After the students broke into two groups, Drayton, Montgomery and their classmate Joy Braswell knocked on their first door. The resident who came to the door gave them a friendly reception, but appeared to not understand English and told them no when Drayton asked if the neighborhood needed sidewalks, crosswalks or street lights.

“People with small children, they’re more enthusiastic,” Braswell reflected as they walked down Goodall Drive. “Then the older folks. It’s the people who are 28 to 45 who are like, ‘Hmmm.’”

“I feel like the older people’s society was a lot nicer, so they’re trying to restore it,” Montgomery said.

Drayton added, “The older folks who are African American, they’re used to having decisions made for them. Now they have a voice and they want to use it.”

Near the end of Goodall Drive, the students found David Allison, a welder, sitting on his front steps. Allison, who doesn’t have children of his own, said his primary concern is Smith High School, where his voting precinct is located. He said he favor demolishing the school, segregating out the troublemakers and then floating a bond to pay for new facilities.

The UNCG students were well aware that the city of Greensboro is not responsible for public schools, but they exercised their discretion to not mention that to Allison so as not to puncture his enthusiasm.

“The thing is everyone wants to tackle the little stuff,” Allison said. “Sidewalks — we could do that ourselves.”

“That’s why we need to hear your voice,” Montgomery said.

“For something like that we need the Gates Foundation,” Allison rejoined.

Montgomery urged Allison to organize his neighbors to come to one of the public input meetings to build a consensus behind his idea.

Drayton visibly winced when Allison referred to Smith High School and Dudley High School as “pre-prison schools,” but she congratulated him: “You’re the first person to give us feedback.”

The students had more luck finding residents with practical ideas in the Lamrocton neighborhood.

At least two residents said they wanted an additional streetlight on Lamroc Road.

Lamont Manning listened quietly to the volunteers’ presentation. Then, without missing a beat, he said, “I need a light right here. It’s really dark.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Kotis Properties budgets the police–many of whom fully participate.