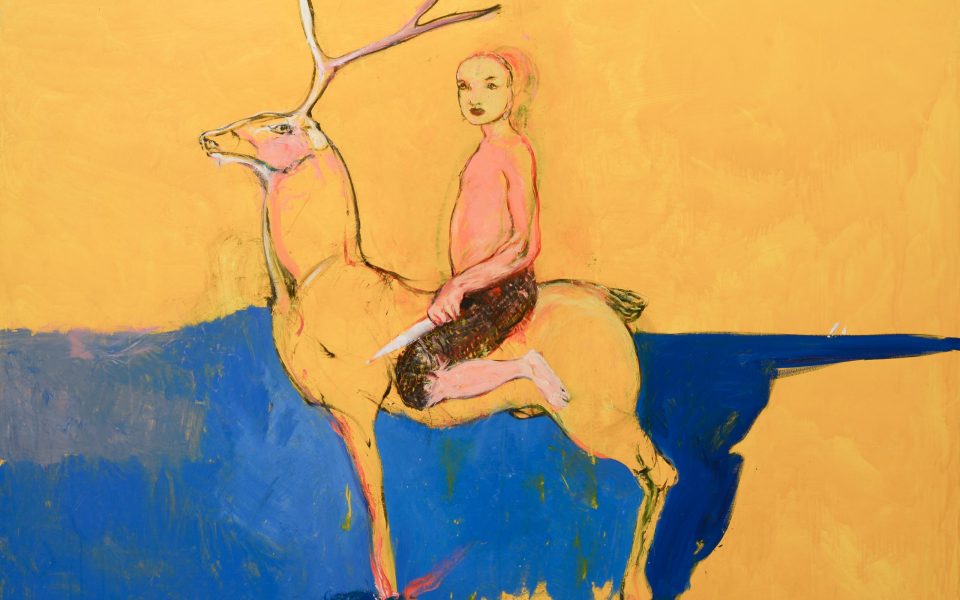

From time to time, Carlos Quintana spits, urinates or spatters beer upon the androgynous, raceless humanoids appearing on his giant, color-saturated canvases. Sometimes he frenetically turns them on their heads so that the vivid oil paint might drip unpredictably.

He is one of 19 contemporary Cuban painters, sculptors, photographers, videographers and installation artists with works recognized in a new exhibit Cubans: Post Truth, Pleasure, and Pain, at the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Arts, on display through Nov. 4. The exhibit — one of the first in the Southeast to feature Cuban artists exclusively — comes four years after former presidents Barack Obama and Raúl Castro reestablished diplomatic relations, rekindling Americans’ interest in the country roughly 100 miles south of our nearest border.

Quintana’s at once dreamy and disquieting artifacts of gestural violence reside in profound contrast to the Vae Victis Vanitas series, Geandy Pavón’s ongoing black-and-white photography project documenting former Cuban political prisoners currently living in exile in the United States, on the adjoining wall. They are no longer young men; wild, white eyebrows reach towards Pavón’s film camera lens aching to tell what they’ve seen. “Vanitas” is a term from the 17th Century Dutch Baroque genre, which frequently included symbols of death, evoking reminders of the transience of life. Pavón replaces still-life skulls with very much alive faces. The Latin phrase “vae victis” translates to “woe to the conquered,” stemming from a legend about the Gauls’ devastating sack of Rome in 390 BCE; those conquered find themselves at the mercy of their conquerors.

Selections from prolific self-portrait artist Aimée García’s series Repression illuminates the political as personal; focusing a career on self-portraiture in an authoritarian collectivist state is quite the political act considering, too, that García is a woman. She overlays her oil-on-wood paintings with fabric and thread fibers, articulating freedom curtailed through tightly-sewn blood-red threadwork and edging the restrictive prison-like bars — perhaps symbolizing censorship and subjugation she incurs — into the viewer’s material space. Her gaze is nervous, but steadfast.

But the story of modern totalitarianism in Cuba is incomplete, told solely through political lenses. Several artists featured in the exhibit approach their work through psychological and sociological frameworks, tackling gender, sexuality, race and religion.

Rocio García is among them. “Sequence Shot 12. Like the Last Blues” from her series The Thriller, depicts a moonlit hell for three naked, male-bodied captives in a building on the shoreline, yet so distant in their bondage from the ship traversing the sprawling sea around their island home, another escaping at risk of death in the far background. The captives’ keeper drinks champagne, shirtless, pants unzipped, a bowtie on the table. They look at each other, powerless. García no doubt touches on male power on a systems level but also the interpersonal; she is distinct among Cuban contemporaries for addressing homoeroticism as a recurring motif in her paintings. Her body of work points to the ubiquity of the erotic, especially given that political and social power hinges on domination, and this is true beyond the borders of her homeland.

Americans do not need to wonder, Who are the people of Cuba? Because they are just like us. They are already telling us, if only we choose to look and listen.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply