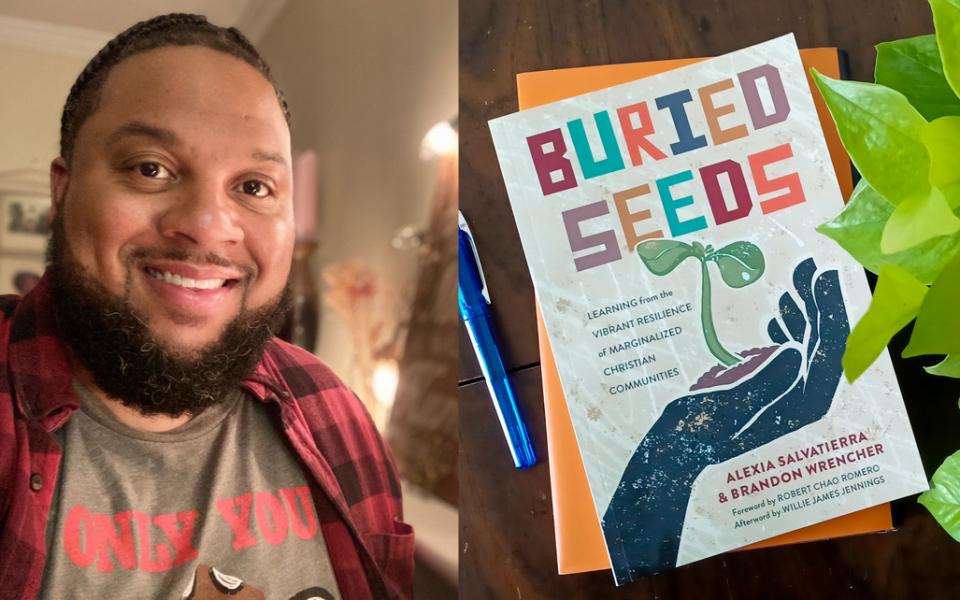

Brandon Wrencher is a senior organizer with Guilford For All and the founder of the Good Neighbor Movement in Greensboro. In October, Wrencher’s second book, Buried Seeds, was published. The book takes a look at how hush harbors of the American Deep South and base ecclesial communities of the Global South offer strategies for modern church and social-justice movements.

On Sunday, Dec. 18, Wrencher will be talking about his book at Scuppernong Books in Greensboro at 2 p.m.

Tell me about your background.

I’m from the Sandhills area of the Piedmont and I come from a Black, working-class family, small-town life. I grew up in two different Black church traditions: Baptist and Holy Pentecostal; there were no more than 50 or so people in those churches. I grew up in those traditions, but what shaped me more than that was the faith of my mother.

She grew up with a faith background but was always a free-thinking person; she would question things and was willing to question the status quo. In most Black Baptist churches in the South, women aren’t supposed to be speaking up, but my mom did that. She wore pantsuits and earrings and lipstick; she was sassy. I didn’t realize that was a problem for her until I grew up.

And as I learned more about Jesus, I was like, Jesus is like my momma.

Then when I went to college at UNC, I fell away from faith. But I was introduced to womanist philosophy, and that changed everything. It changed me to be an organizer and a minister.

How did you come to Greensboro?

I was asked to come to Greensboro to start a faith community in 2017 by the United Methodist Church. It was to be a downtown community that was multiracial and led by Black folks. I started the Good Neighbor Movement that year.

Starting any faith enterprise is just a really difficult thing to do. It takes a certain kind of energy and leadership. Most church plants are kind of gentrifying forces. They don’t root themselves in a place; it looks much more extractive. I recognized immediately, This doesn’t feel good. So I sought out mentors of mine.

I started talking to people like Rev. Nelson Johnson and my co-author Alexia Salvatierra, and I began listening to them. And we were like, “You know, maybe we have in our lineages, Black and brown lineages, the seeds of what it means to start new faith communities for spiritually underserved communities.” Through an organizing path rather than a kind of social entrepreneurship or business model of starting a new venture.’ That’s when we began to read more about the two traditions that formed the basis of the book.

Tell me more about the traditions of base ecclesial communities of the Global South and the hush harbors of the US Deep South.

So base ecclesial communities were a movement within the Catholic Church mainly in the global south, mainly in Latin America. It was a response from people who were not ordained, who were poor, who could not afford full-time clergy in their parishes.

From the very beginning it was an act of protest, a justice act to say, “We deserve to be able to have houses of worship where our leadership can be developed and where we can have the full range of what it means to be a faith community.”

What happened is that these poor folks, brown and Black folks, began to form their own faith communities. They were led by non-ordained folks from working-class backgrounds as small groups who shared leadership.

Hush harbors were similar. Enslaved Africans were only permitted to worship in two different ways: in multiracial but predominantly white churches where white ministers had power, or in slave quarters with a Black congregation but also white leadership. These were still in the gaze of white supremacist religiosity.

Then, some enslaved Africans said, ‘These are false choices; our worship shouldn’t be controlled.’ And they went off into the woods at night illegally. They would take bits and pieces of what they learned about Christianity and blend it with African traditional practices and made a faith and church of their own outside of the surveillance of the plantation.

They were an unsettling force. They were the buried seeds that really animated so much of the movements at that time including the abolitionist movement.

It seems like younger generations don’t consider themselves religious, but you push back against that notion in the book.

It depends on what we mean by church and religion. In those backgrounds, they pushed back on what the definition of church and religion is. What I try to show in the book is not just what’s happening in the past, but examples of where young people — any people — who have left institutional religion have found meaning making or spaces to make big changes in their lives. That these function in similar ways to what religious institutions used to function as. Places like barbershops, activist groups, artist spaces — these function for many people as sacred spaces. They may not have doctrine; that was what I was after.

I want to push back on that narrative without being insensitive to that. Tons of young people have an absolute allergy to the ways organized religion operates today because it can be hateful. But to be critical or to refuse does not mean we limit what can be and what we create for us. And if we are going to have a power analysis where we learn how to resist the most fascist and, frankly, evil forces, we can’t discard and dismiss comrades because we need one another.

What do you hope the future of Christianity in this country looks like?

When I think about my ancestors and the risks that they took to create sacred spaces that would feed their souls, that would love their bodies, that would free them to fight for a world where nobody is without or where nobody is treated without dignity, I don’t believe that is limited to Christianity. But I think that Christianity still has ingredients for that kind of movement to rise again in these times, just look at the Poor People’s Campaign. So it’s less about where I want Christianity to go in this country, but where I want to shift attention.

I want to focus more on these clandestine, off-the-beaten-path, grassroots ways we live out spirituality and faith that is much more about love of self, love of people and a desire for a world where everybody and every creative thing belongs. That is happening all over the place. My desire is that we learn to be good cartographers so that we can map and find and honor those places, because those places will always be there. That’s the idea behind buried seeds — they are always there.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply