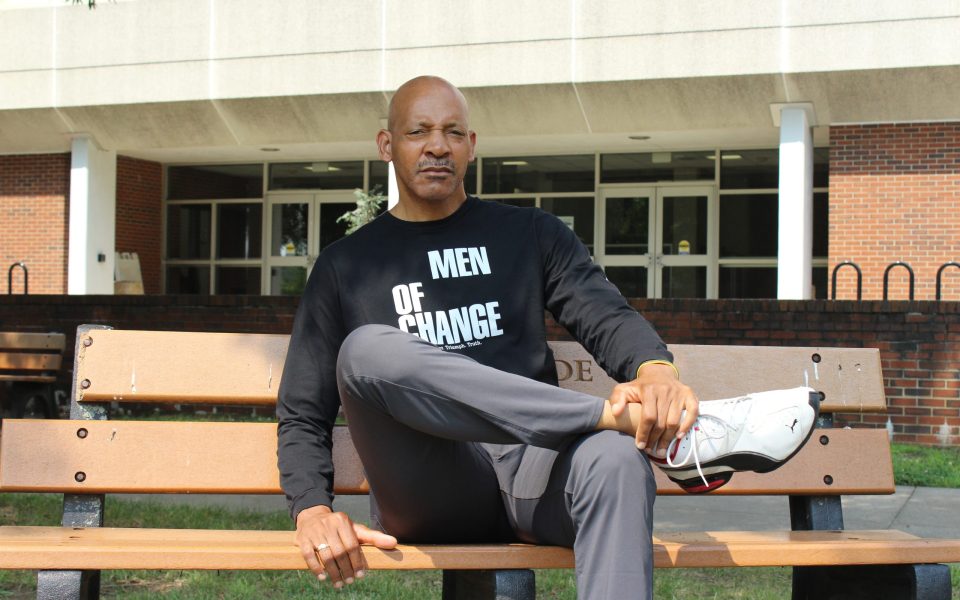

Featured photo: Dr. Robbie Morganfield, who most recently held the position of professor and chair of the Department of Journalism and Mass Communication at NC A&T State University, will soon be heading the Ida B. Wells Society at Morehouse College. (photo by Sayaka Matsuoka)

Dr. Robbie Morganfield has worked in the journalism industry for close to four decades since he got his start as a staff writer for the Sun Sentinel in Ft. Lauderdale in the mid ’80s. Since then, he’s covered city government as a staffer, reworked writers’ copy as an editor, taught at multiple universities as a professor and, most recently, held the position of professor and chair of the Department of Journalism and Mass Communication at NC A&T State University.

In the next few weeks, Morganfield will be transitioning into his new position as the director of the Ida B. Wells Society which will soon be housed at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

The Ida B. Wells Society, which focuses on increasing and retaining journalists and editors of color in the field of investigative reporting, was founded by four Black journalists, including Nikole Hannah-Jones, in 2015. The society moved from Harvard University to UNC-Chapel Hill in 2019. In 2022, the school appointed Hannah-Jones to a named chair of Journalism at UNC’s Hussman School of Journalism and Media. But, as thoroughly reported by NC Newsline’s Joe Killian, only a month later, the UNC Board of Governors refused to vote on giving Hannah-Jones tenure. Afterwards, Hannah-Jones left UNC and announced that she would join Howard University to start a journalism center there with Ta-Nehisi Coates. Now, Morganfield is taking his four decades of experience to further the mission started by Hannah-Jones at Morehouse College.

Morganfield talked about his career, what it’s like being a Black journalist now versus then, and where he hopes the industry is going.

Congrats on landing the Ida B. Wells gig. That’s huge! How did that come to be?

I had actually started dating someone in Atlanta, and I was really interested in moving. I wanted a relationship and wanted more balance in my life. I love my job at A&T, but socially, Greensboro never really captured me because I’ve always loved big cities.

So when I saw the posting and heard that they were moving the society from Chapel Hill to Atlanta, I thought that it might be a good fit for me.

Fortuitously, Nikole Hannah-Jones had been talking about partnering with A&T for her Center at Howard and she and her people were talking about coming down. So she came down and I happened to be the one that took her back to the airport. It really kind of grew from there. We got to talking, she invited me to apply and the interview went really well

Why were you drawn to the job?

I saw the job as an opportunity to broaden my reach in terms of impact. I’ve always tried to look at whether or not I’m making a difference, especially in the lives of young people of color. I always loved working with youth and young people because they give us energy, but also because these are the people that will follow us and hopefully they do it well.

For example, when we were putting together a masterclass on data journalism and investigative journalism at A&T, it turned out that two of the people to put on the masterclass were from the Ida B. Wells Society and they were my former students: Corey Johnson (who had just won a Pulitzer Prize) and Topher Sanders, who was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize. They had both gone through my diversity program at Vanderbilt University. (Both Johnson and Sanders co-founded the Ida B. Wells Society.)

The Ida B. Wells Society position would put me in a different kind of space and allow me to continue to do the kinds of things that matter to me — to allow me to work with students across the country, and even work with students at high schools. Plus, I’ll be working with people in the industry. I can’t turn it down. I’m beyond thrilled to have this opportunity but I’m leaving A&T, which is probably the best job I’ve ever left.

Tell me about your background in journalism.

I grew up in Mississippi and started writing when I was in high school for my high school newspaper. I decided I wanted to be a journalist and attended the University of Mississippi and earned my bachelor’s degree in journalism. My first two years out of college I worked in public relations and absolutely hated it. I always intended to be a journalist.

Then I got a reporting job in Ft. Lauderdale. It was a daily newspaper and I started out covering city government. I eventually moved into covering schools and higher education, and then after that, I landed a job at the Detroit News at a time when newspaper jobs were vibrant.

I got a masters at Ohio State in public affairs reporting. Went back to the news, did some more reporting, won some awards, ended up leaving. I was thinking I was going to become a minister at one point; I went to bible school for one year. Then I was working as a reporter covering city government at the Tulsa Tribune, which was an afternoon paper; I would be the only reporter when I would get there. I did that for one year, then I got the invitation to go and teach. Then got the job at the Houston Chronicle. Went back to school again, went to seminary at Texas Christian University for three years, got to the end of that journey and said, I’m not going to be a minister. Then I was a specialty editor at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. After that I ended up in Nashville working for the Freedom Forum. Left there to get a PhD at Maryland College Park where I was a pastor while I was a full-time PhD student. I stayed in DC for 10 years and then directed a program at Grambling State University in Louisiana. In 2020, I left there to come to NC A&T.

My career has been bursts here and there. I recently came to the conclusion that I’m like a rolling stone; I like to roll in and roll out.

Once, I entertained the idea of enlisting in the military because I wanted to see the world. I think I got into journalism for the same reason of chasing my ambitions, of living in different places.I think I’ve lived in 11 or 12 states over time as a student or working professional.

That’s a hell of a résumé. It shows you’ve been in so many different areas of the industry for a long time. How do you feel like journalism has changed since you’ve been in it?

One of my big passions is advocating for free press and the importance of it, especially in terms of people being informed and aware. I know that we cannot trust politicians to be the voice to tell us everything we need to know. I’m not anti-politician but I believe in checks and balances and I believe in the free press to be a part of the checks and balances. You know, they say in J-school, “If your mama tells you she loves you, check it out.”

This job is extremely important now, I think more than any other time in my lifetime. Everybody wants to put out information regardless of whether it’s good or bad information so the public is bombarded. We have to have systems to navigate that so the public can vet information and determine if it’s reliable. Also, different voices are essential. As an African-American male, I know from my own experience that our voices have not always been welcome and they haven’t always been included in conversations about public life and reporting.

Talk a little more about that. How has your identity as a Black man impacted your work as a journalist?

It’s a very cyclical issue. It calms down for a while and then comes right back. I came in at a time when there was a diversity push in the ’80s. I came into the industry when diversity was being promoted. I was really fortunate. I came in at a time when you could really grow as a journalist; I was able to write my own ticket in a lot of ways. I traveled with George W. Bush when he was running for governor of Texas, I got an Associated Press award for investigative reporting.

But I think the problem is that there are always places where people find acceptance and where they find resistance. There can be some passive-aggressive nature in newsrooms. In some instances, people of color are hired but the environment is not welcoming, not supportive. And when you brought it to the attention of some editors, they would defend it.

Do you think it’s better now? Are things moving in the right direction?

I don’t know that I think it’s necessarily better. I do see some signs in recent times. I’ve known quite a few African-American women in part who have been promoted to positions like editors and that’s something that I didn’t hear back then. But then I do see some signs where it is regressing.

Disinformation is at the core of a lot of the campaigns you’re seeing: anti this, anti that, where anything that is progressive or forward thinking is being attacked. Like the law in Florida banning school teachers from teaching history in a certain way because it makes some people feel uncomfortable. How ridiculous is that? I mean, I was uncomfortable with how history was taught when I was growing up. The way that Black people were depicted. And now, they’re passing laws to protect the sensibilities of white people. That’s the most ridiculous thing I’ve seen in my whole life.

You’ve talked about the role of religion in your life. How does faith and reporting intersect for you?

Historically, most of the first reporters were pastors. The idea of liberation and democracy intersect with religious thought. It’s disheartening when people use religion not to liberate people, but to incarcerate people, to marginalize people.

Religion is a matter of faith, not necessarily fact, and so I’ve seen what the power of what faith can do in my personal life and my family. But I find that a lot of conventional thought about religion is problematic. The journalist in me and the Christian in me questions that.

What’s your favorite part about journalism?

My favorite part is the ability to tell stories and provide people information that helps them make meaningful decisions in their lives.

Becoming a journalist made me more able to talk to people and people learn from stories, people remember stories. I think storytelling has a real vital place in our society and I think as journalists, we get to do that.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply