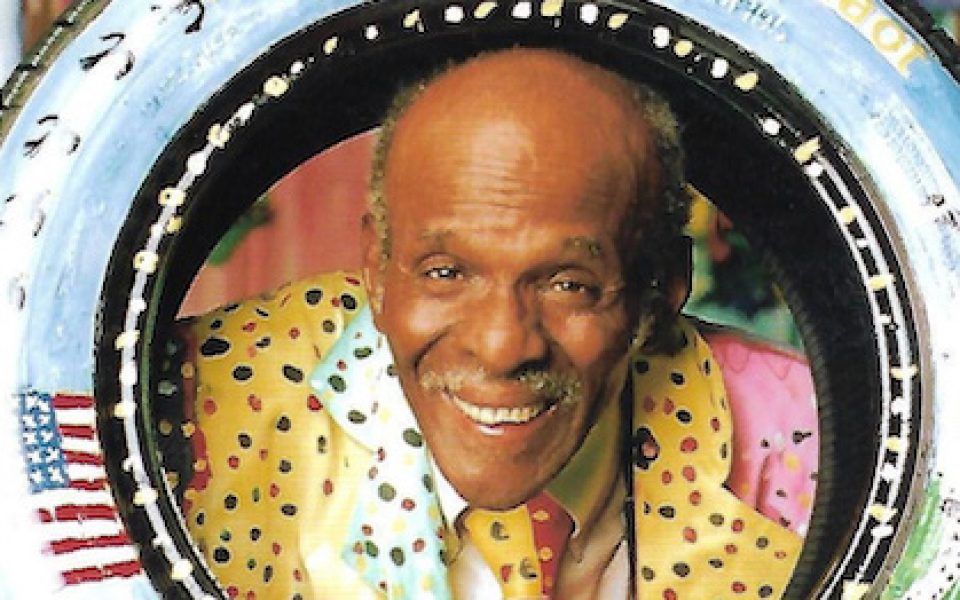

“The Dot Man” kept his studio doors open, and his prices low. Passersby could peruse a “petting zoo” of artwork in his front yard. He would eat a half gallon of ice cream in one sitting. He talked a mile a minute.

Sam “the Dot Man” McMillan was born in Robeson County in 1926 and grew up the youngest of 10 children in a family of sharecroppers. He moved to Winston-Salem in 1977. He chauffeured and made furniture before working for DeWitt Chatham Hanes. Then, in his late sixties, he picked up a paintbrush and hardly let it rest.

In the wake of his passing last August, the Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art in Winston-Salem is showing Remembering Sam, a modest memorial exhibition of the prolific, self-taught artist’s work from public and private collections, through March 10.

“The community response was amazing,” says Wendy Earle, curator of contemporary art at SECCA. “We had over 175 people attend the reception, and many came decked out; we saw all sorts of Sam’s work being worn: overalls, jackets, hats, shoes, purses and many, many ties that he had painted. We had to keep the exhibition small because of the size of the gallery, but Sam was so prolific that we could have filled all 10,000 square feet of our gallery spaces.”

McMillan was an “outsider artist”: self-taught, free from the mainstream art world, often living at the margins of society. Outsider artists’ works are typically two-dimensional and unconcerned with realism.The “Dot Man” moniker stems from Sam’s characteristic use of brightly-colored, frenetic polka dots.

“Some people put dots on things — Sam put dots on things to bring them alive,” says Bob Moyer, a longtime friend and collector of McMillan’s work. “They just don’t sit there or look nice. They have a life of their own.”

Moyer owns more than 40 of Sam’s pieces: just two of the paintings among objects like his kitchen table, bureaus and the desk featured in the exhibition. After meeting in 1992, Moyer sat in Sam’s studio often, exchanging conversation and observing Sam’s instinctive process as others popped in and out. “The Dot Man” would work on one piece, set it aside, pick up another, return to the first, pick up a third — until he felt they were finished.

“It’s intuition,” Moyer says. “The guy is using what he knows, what he sees. There’s not a piece that’s not connected, because it’s all connected to Sam’s mind… and this is why I love outsider art: There is no thought; they see things, they paint. The thing they see may be a vision. Howard Finster saw visions, religious stuff. A lot of religious outsider artists.”

Sam painted with bicycle enamel out of a studio on Northwest Boulevard across from the Hanes Dye and Finishing plant.

“Once you’d walk into it, you’d be amazed,” one of McMillan’s sons, Kenny, says. “Everything was painted: the ceiling, the walls and then all the artwork hanging on the wall. It really struck you as you walked in the door. It was kind of fascinating. A kid walked into his shop, you could see their facial expression change. It was a warm feeling to see that from this man who started painting at 67 years old and became famous.”

A much beloved member of Winston-Salem’s arts community, Sam taught classes for children in his shop, local elementary schools and at the UNC School of the Arts High School.

“He taught the younger generation how to respect themselves and how to be respectful in the world,” Kenny says.

A child never left the shop without a gift. Sam’s work reveals his idealism, and his dream that young people would cultivate racial unity in the decades to come, among other themes like disdain for consumer culture.

“There’s the one piece with the children [of different races] holding hands. My father’s artwork was trying to give a message to the world, and his life motto was: If we hold hands, we can’t fight,” Larry, another of McMillan’s sons, says. “My dad… cared about everybody. In his older days, being 90-something-years-old with dementia, he did get into his cranky ways. But he loved everybody.”

People who knew him also describe him as generous, as someone who donated to local non-profits and freely offered his works to fundraisers. And he had plenty to give: Moyer says that if he created something he liked, he would paint 50 more. Bookends, birdhouses and ties littered his studio before migrating through Winston-Salem or across oceans. He once drove to California to paint a man’s pickup truck.

“One story I love to tell is about the ties,” Moyer says. “There’s a white tie [hanging in the exhibition]. It was a silk tie meant to be painted on. He hated it because his paint didn’t work well on it. His solution to that problem was go to flea markets and buy and paint on old ties. Every other tie looks better because it fits Sam’s mode of working, and so you’ve got a history of ties in front of you. He looked at all the ties like they were the same tie.”

In New Orleans’ Ninth Ward, travelers request the “Sam McMillan Room” in the double shotgun called the Bywater Bed & Breakfast, filled with the man’s dotted furniture: side tables, a rocking chair, a chest of drawers.

“He spread his work and so he spread his spirit, of making people smile,” Moyer says. “It’s hard to look at something Sam painted and not smile. Sam’s career was a lesson in not getting in the way and not holding on. Now the world’s full of Sam’s stuff because he never held onto it.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply