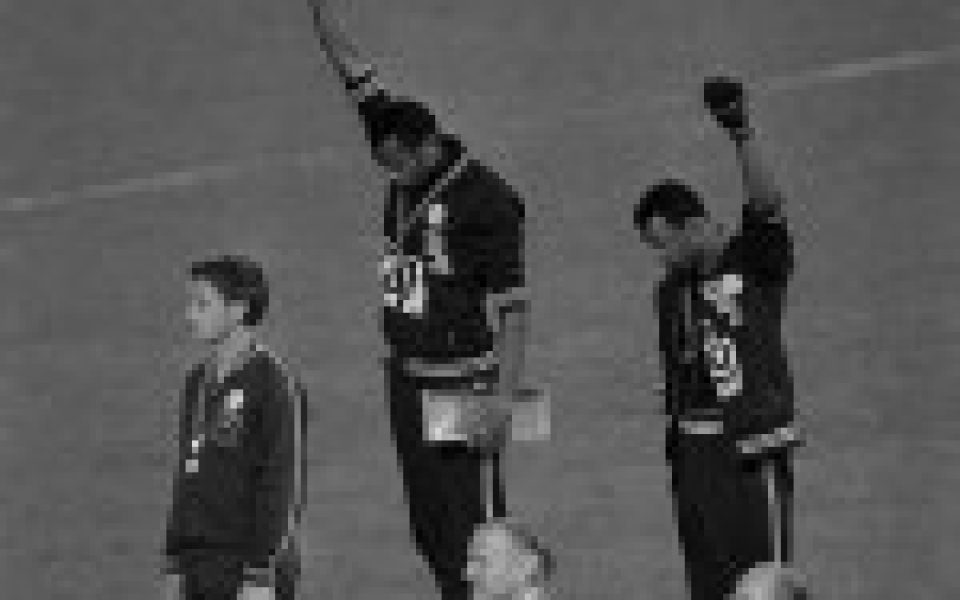

In Mexico City in the summer of 1968, US Olympic runners John Carlos and Tommie Smith raised their black-gloved fists during the National Anthem. The gesture was one of solidarity, resistance and black power, of unimaginable meaning to millions at home. Both men were suspended from the team, ostracized, subject to threats and abuse.

Not until the past few years have sports figures and the greater world around them witnessed the same political and racial tension that moved these two men to undaunted political demonstration nearly 50 years ago.

There is no question as to whether or not the contemporary world of sports intersects and mirrors our country’s intense political climate. San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, for example, continues to receive criticism for refusing to stand for the National Anthem that he felt does not represent him. His decision inspired hundreds of athletes from many backgrounds to follow suit, often resulting in further criticism and even threats. In contrast, Under Armour recently expressed support for President Trump while continuing to profit from sales to children of color whose lives Kaepernick’s dissension directly addresses.

The contention surrounding political stances in professional sports raises an important discussion about the position of influence held by athletes.

Cherizar Crippen, co-chair of communications for Black Lives Matter Greensboro and a political science student at GTCC, stresses the power generated by athletes taking a stand. Much like the physical stances of Smith and Carlos at the 1968 Olympic Games, an athlete’s voice and actions can be symbols of solidarity against oppressive forces, she contends.

But to Crippen, an athlete’s or athletic company’s choices can sponsor the side of the oppressor to an equally powerful degree.

“Companies like Under Armour coming out in support of Trump while their gear is worn by members of marginalized communities and the complicit silence of Tom Brady in the wake of Richard Spencer’s tweets during the Super Bowl are both harmful,” Crippen said, referring to racist, pro-Patriots tweets from the white supremacist Spencer.

Yet for Thomas Santiago, a 22-year-old student at UNCG who coaches Crippen’s nephew in a youth basketball program in Greensboro, the influence of famous athletes is overemphasized.

“We need to stop looking to athletes of high status and instead look to restructuring ourselves,” Santiago said in a phone interview. “We look at what athletes have financially, we see what they have that we don’t, and we assume they can help.”

To Santiago, athletes like the somewhat outspoken LeBron James don’t understand most people’s lives.

“He was kept away from that reality from age 13,” he said, referencing James’ early path to NBA stardom.

[pullquote] ‘Eleven- to 13-year olds may not know all the politics, but they can certainly tell you how they feel.’ – Thomas Santiago [/pullquote]

Though there is some discord between the statements from Crippen and Santiago, they are not necessarily on separate sides of a debate. The harmful actions that Crippen referenced were committed by those who promote the damaging systemic segregation that causes Santiago to look toward his own community for guidance. Systemic racial division often leads the contentious discussion of politics in professional sports.

As more athletes of color refuse to be silent, the role and presence of white athletes is called into question. When black athletes and other athletes of color stand in solidarity with oppressed communities, they put their careers, futures, even their safety in jeopardy. This is a sacrifice that many believe should in no way be black athletes’ burden to bear, much less shoulder alone.

Yet lately, the only white athletes to create waves of serious political impact are Tom Brady and Curt Schilling — clammed up in Brady’s case and clamorous in Schilling’s. Both men abandon the actions and statements of solidarity with athletes of color that some feel should be preeminent in today’s political climate.

For Crippen, there’s no question about white athletes’ role in the work to undo the injustices that contemporary politics has illuminated.

“Being a traitor to white supremacy is the highest calling a white athlete or any white person could have in these times of racial tension,” she said. “Athletes would need to make the principled but difficult decision to be willing to risk income for our collective good. I do doubt that the backlash for white players would be as harsh and long-lasting as it has been historically for black players; maybe if they were confident of that it would motivate them to action.”

Santiago, however, expressed a deeply-rooted skepticism that correlates with the very separate lives of black and white communities.

“What we’ve been through as African Americans makes us more confused to the idea of help,” he said, referring to a wariness that grows with each passing instance of flawed or unfulfilled support from those outside of the black community.

“What’s your true motive behind helping?” he asked rhetorically.

Again Santiago cited the need to focus on local community instead of seeking guidance from those of impossible wealth and fame.

“People my age need to look at what’s around us and look for chances to teach and be taught,” he said. “What’s around us are kids. Eleven- to 13-year olds may not know all the politics, but they can certainly tell you how they feel.”

The political influence of athletes has no set measure. They make up an indeterminate part of the collective action that will determine what these kids will have to sacrifice, what burdens they will bear, and what they may have to shoulder alone.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply