by Jordan Green

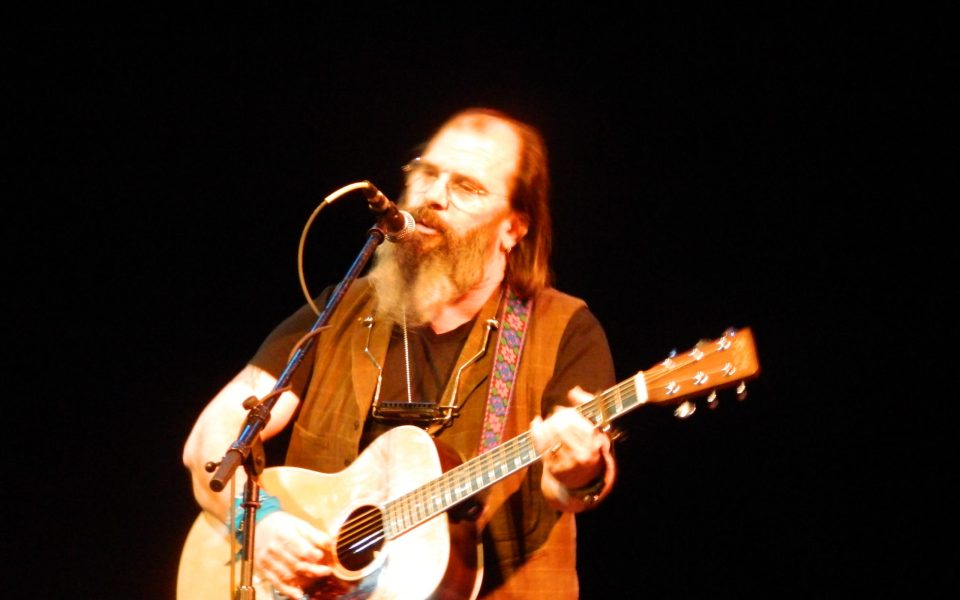

Pushing 60 with thinning hair and a Whitmanesque beard, Steve Earle slung an acoustic guitar and blazed through a four-decades-deep repertoire during his concert on Sunday at the Carolina Theatre in Greensboro.

With only a voice and a guitar — or bouzouki or mandolin, as the case might have been — his expressive vocals and spirited playing easily summoned the “good rockin’ daddy down from Tennessee” who roared onto the scene in 1986 with Guitar Town, the debut album that launched the “new country” movement.

Full of swagger, traditional country musicality and populist indignation even back then, he seemed to emerge with his music fully formed. It’s easy to forget that the Texas-born singer-songwriter came up as a protégé of folkies Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark, themselves schooled under the tutelage of Texas bluesmen Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb.

“I did see Mance Lipscomb and Lightnin’ Hopkins in the same room with Townes and Guy, believe it or not,” Earle told the audience at the Carolina, both bragging and explaining his blues pedigree. He shared that his next album will be primarily blues, and he plans to start recording with his band the Dukes in Nashville in a couple weeks. A collaboration with Shawn Colvin is next, following the February release of the blues collection.

The song that opened Earle’s Greensboro concert from the forthcoming album sounds like it could have been plucked from the early ’60s-era country-blues milieu of Lipscomb and Hopkins with its lightning-fast fingerpicking and jaunty declaration of “ain’t nobody’s daddy now.”

“That’s new, and this next one is not,” Earle said before launching “My Old Friend the Blues,” a song from his first album that still stands as eloquent a testimony to heartbreak as anything ever produced in Nashville short of George Jones.

Earle’s immense talent and restless spirit has translated into a career that sometimes seems to lack coherence and focus, with his new traditionalist foundation melding into hard rock before he slid into the abyss of heroin addiction and returned with a harrowing and defiant burst of songs in early recovery. Since then, he’s made forays into bluegrass and Irish music, sharpened his protest songs during the presidency of George W. Bush and relocated to New York City.

But on Sunday the energetic treatment and emotional commitment he applied to material from the span of his career, with particular focus on Guitar Town and 1996’s I Feel Alright, made his body of work feel of a piece. Wearing jeans, a leather vest, T-shirt and chain wallet, he seemed to embrace the outlaw stance of his youth, while between-song banter about his chemical demons, the impending war with ISIS and the craft of guitar- and mandolin-making revealed a man of wide-ranging interests.

He performed a stunning rendition of “Taneytown,” depicting racial terror in rural Maryland from the 1997 album El Corazon. It’s hard to hear it without experiencing chills, and Earle’s Sunday performance only heightened its emotional power. He hollered and ripped into a fierce guitar solo, followed by a gale-force harmonica piece before nearly dropping down to a whisper and then rebuilding to empathetic rage as he spat out the lyrics.

A series of songs in the middle portion of the set chronicled Earle’s recovery from addiction. He dedicated the romantically haunting “Goodbye” (“Was I just off somewhere or just too high/ But I can’t remember if we said goodbye”) to Emmylou Harris’ mother, who recently passed away, noting that it was the first song he wrote after his four-and-a-half-year hiatus. He gave a spirited and pissed-off performance of the title track from I Feel Alright (“Some of you would live through me, lock me up and throw away the key”), although not as pistol-quick as 19 years ago.

He performed “South Nashville Blues,” an archaic-sounding reverie for the wild side of life.

“It has one fatal flaw: It makes that part of my life seem like more f***ing fun that it really was, particularly near the end,” Earle told the crowd. “For the last 20 years and eight days, whenever I sing that song, I also sing this song lest I forget.”

Then he played a version of “CCKMP (Cocaine Cannot Kill My Pain)” that sounded every bit as harrowing as the day it was released in early 1996.

In 1986, Steve Earle sang “Little Rock ‘n’ Roller,” a trucker’s goodnight phone call to a child from “somewhere on the Arkansas line.”

In Greensboro on Sunday, he talked about going home to New York City the next morning, lugging three guitar cases up the stairs to his third-floor walkup, retrieving his van from the shop and picking up his 4-year-old, John Henry, from school. He talked about how John Henry stopped speaking and was diagnosed with autism at 19 months, and how fortunate he feels that his son likes to be touched and enjoys being around other kids. He expressed gratitude that the city of New York picks up the cost of the special services John Henry needs. The singer-songwriter-father is keenly aware that he will need luck and good health on his side to see his son grow into adulthood.

And then he sang a song called “Remember Me” about how fleeting life is.

It turns out that the distance of time, geography and culture is not so far after all.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply