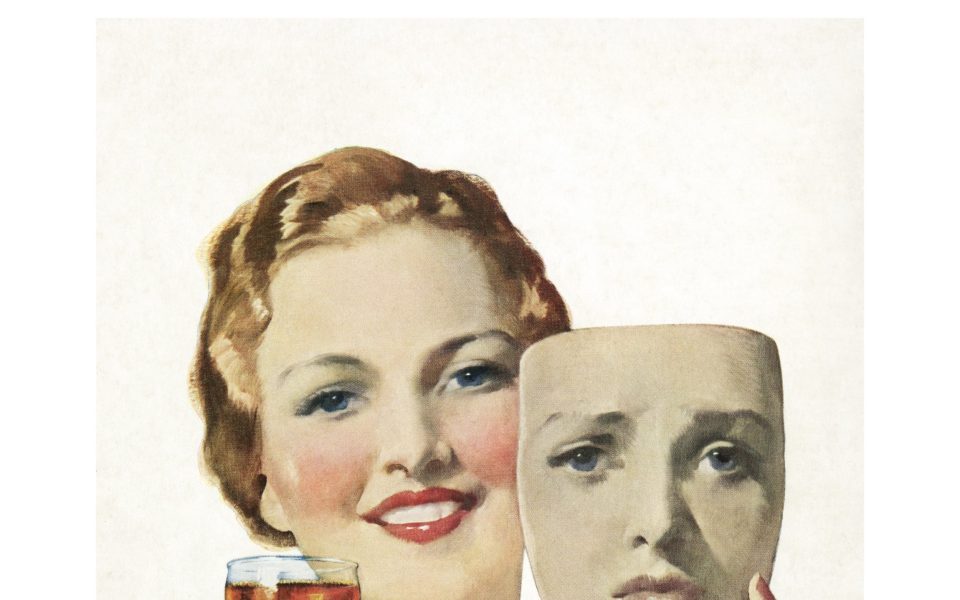

The images that comprise Hank Willis Thomas’ exhibit, Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015, piece together a complex narrative of their subject’s story through the past 100 years: increasing autonomy and idealized beauty set in opposition to racialized otherness.

Further complicating the story, a counter-narrative of backlash periodically pushes against the story of liberation, with images that suggest efforts to dominate and control women, subjugate them as objects of male desire and punish them for their independence.

An abbreviated version of the exhibit, on display at the Weatherspoon Art Museum through Dec. 11, commandeers two lower galleries of the museum with a chronological presentation of advertising images, with the both the original text and brand identification stripped away. What’s left is the underlying imagery used to manipulate desire by playing on powerful and unexamined feelings. By removing the product placement, Thomas hopes viewers will look more closely.

One image in the full exhibit, but not included in the abbreviated version on display at the Weatherspoon, made a distinct impression on me as a 12-year-old subscriber to Rolling Stone. Three young women in one-piece bathing suits sprawl across an oversized beach blanket draped over a wooden deck with the ephemera of beer cans, portable CD players and books laying around. The colors of the women’s bathing suits are strategically aligned with those of the beach towel, which even with the words removed is easily identifiable as the Budweiser motif. The woman in the middle of the trio smiles in a way that is both provocative and demure. The insidious message is pretty unmistakable: Women are an alluring, but controllable facet of a carefree experience with alcohol; they’re literally melting into the woodwork — and the brand.

I doubt that I picked up on those subtleties as an impressionable 12-year-old, but I definitely took note of how weird the whole thing was. Such is the power of a jarring image that captures our attention without us really knowing what’s happening.

©

“I want people to think twice about what they are buying into, literally and conceptually, when they buy a product,” Thomas has said in an interview with his mother, photographer Deborah Willis. “Advertising is a form of social conditioning and brainwashing. It is beautiful in its ability to communicate really complex ideas, but it is also sinister in its capacity to do that.”

The exhibit doesn’t announce the fact that the images are excavated from advertising history. A laminated cheat card in each of the galleries matches the original text to the images, but does not identify the associated products. Some viewers may find themselves absorbing the exhibit at surface level, which provides its own layer of fascinating meaning.

During my visit on Tuesday, I observed two elderly white women leisurely strolling through the exhibit, lingering over an image of a young woman in civilian scrubs working in a 1940s era war industries plant. One of them remarked with a pride about a female family member who worked in the war industries in Alameda, Calif. during the war.

“Some of them didn’t want to give those jobs up,” the woman said. “They liked the freedom. They liked earning money and getting out of the house.”

When they progressed through the exhibit and landed at a 1982 image of a woman’s face angled directly at the camera with a bisecting line dividing a smooth, beautiful and relaxed visage from a garish, almost skeletal version with deep wrinkles and a shadow under the right eye.

“Look at this before-and-after,” one of the women said. “We’re not that bad, are we?”

“That’s what the beach will do to you,” her companion replied.

A Century of White Women functions as a kind of sequel to a previous project, Unbranded: Reflections in Black by Corporate America, 1968-2008, which examined media images of and for black consumers. Thomas, who is black, has said that he doesn’t feel an affinity with the images in A Century of White Women.

“I always like to stress that the craziest thing about blackness is that black people never had much to do with creating it,” he said in his interview with Willis. “It was actually created with a commercial interest in order to turn people into property. The colonialists had to come up with a subhuman brand of person, and that marketing campaign was race. So much of the conversation about race is spent talking about blackness and black people, but it does not, and rarely addresses whiteness. Whiteness was constructed to give certain people an upper hand, and we, brown people all over the world, have been contending with this oppositional hyperbole for centuries.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply