UPDATE: On July 3, just one day after this article came out and less than a week since the actual mural went up, the muralist went back and edited the image.

There’s so much to unpack.

Just hours after Greensboro muralist Brian Lewis, popularly known as Jeks, posted a picture of his recent creation on social media, people began dissecting the image and its complicated history.

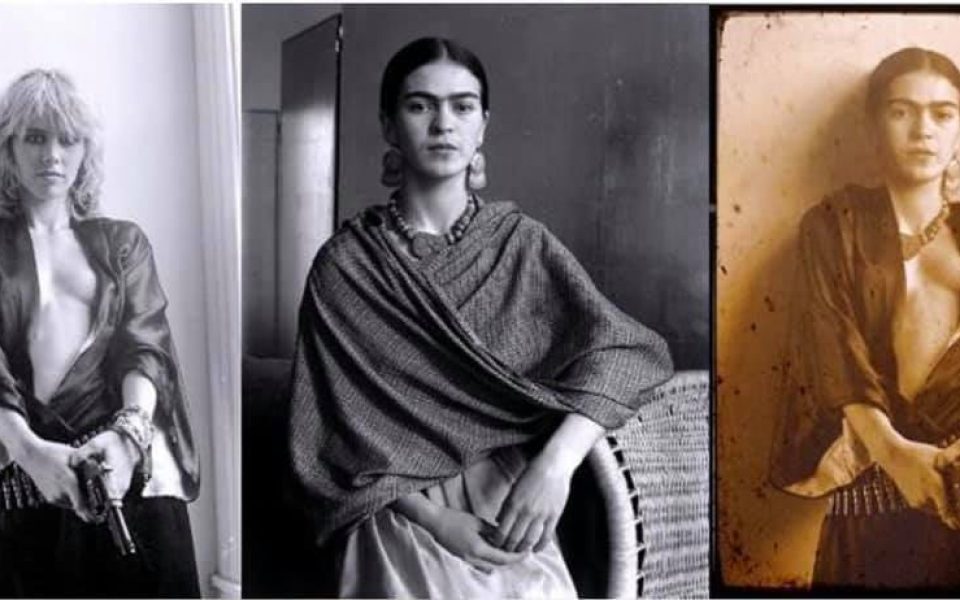

The giant mural — which is painted on the back of Heraldry Arms, a gun shop inside a building owned by Greensboro developer Marty Kotis — depicts a scantily clad Frida Kahlo, unibrow and all, holding a revolver with both hands. She stares out intensely at passersby who drive past Pig Pounder or are on their way to RED Cinemas. On social media, it’s been even harder to ignore.

And therein lies the first main problem with the piece.

It’s fetishizing.

For centuries, women of color of all backgrounds have been fetishized by white men for their “exotic” features. “Sexual chocolate,” “yellow fever,” “spicy Latinas.”

This is no different.

Kotis, who commissioned the piece, said the owner of Heraldry Arms, Jay Bulluck, was the one who picked the image as a symbol of female empowerment. In a statement sent to TCB by email, Bulluck says that “the mural was neither commissioned by me, paid for by me, or painted by me. I’m truly sorry for any pain felt by the Triad community.” When asked whether he chose the image, Bulluck refused to confirm whether or not he selected the image.

Still, you have to wonder. Did any of these three men ask women they knew if they felt empowered by the image? Any Latino women? Any queer women of color? Any disabled folks?

Probably not.

And Kahlo was all of these things.

In a Facebook comment, one poster said it best. The image distills the famous Mexican artist and activist down to a single identity as an “NRA pinup.”

Kahlo had a complicated relationship with her body. As a child, she contracted polio which made her legs different lengths. When Kahlo was 18, she famously suffered a horrific traffic accident in which the bus she and her boyfriend were riding in collided with a streetcar. An iron handrail impaled Kahlo through her pelvis, fracturing her pelvic bone. Over the next 30 years, Kahlo spent much of her life battling one disease or ailment after another. She suffered multiple miscarriages and was mostly bedridden the last four years before she died.

In her self-portraits, Kahlo often depicted herself in lavish settings with her pet monkey and her signature flower crown, but also conveyed complex feelings about her body and trauma.

Graphic paintings of her miscarriages and “The Broken Column” show Kahlo in some of her most traumatic moments.

“So much about the image is the erasure of Frida Kahlo while preserving the cool status,” says Fahiym Hanna, the owner of Sensuous Scents in Greensboro, which boasts another mural by Lewis of Nipsey Hussle. “The hero status that is generally exploited for capitalistic gain.”

Hanna cites other figures like Che Guevara who have been used in this same way to sell merchandise.

Hanna, who is perfectly happy with how the Nipsey Hussle mural turned out, says that the difference between the two works is how the art came to be.

In this instance, he says that he met with other vendors and invited members of the community to talk about what a tribute to the late rapper might look like. Once they settled on an image, they hired Lewis to paint the mural. They made sure that no guns were in the image. They didn’t want to romanticize gang violence. No scantily clad women either. It’s not what Hussle stood for.

It’s a vastly different situation with the Kahlo piece.

This is an instance where three clueless white men decided to make a work of art and then after members of the community — mostly women and many who identify as LGBTQ — spoke out against it on social media, their criticisms were ignored or even deleted.

Lewis has deleted negative comments on his Instagram and the Heraldry Arms Facebook page went inactive the same day.

“Unfortunately, important voices were silenced when a social marketing company for Heraldry Arms deleted the conversation on the Facebook without consulting me,” Bulluck wrote in his emailed statement. “They have since been terminated and subsequently, the FB page rendered unpublished.”

Kotis says that he doesn’t mind receiving feedback but that changing the mural goes against his values as a libertarian and a “champion of free speech.”

“I’m not a big fan of censorship of art overall or kind of crowdsourcing art,” he said on Monday. Well, deleting feedback seems like censorship to me.

This also all went down while Kotis was in Washington, DC for a “research trip” into Mexican culture. And yet he still doesn’t see how minimizing one of the greatest Mexican artists and activists into a pin-up doll isn’t offensive? The blatant cognitive dissonance astounds me.

In an email on Tuesday, Casa Azul, a local artistic collective that focuses on Latinx culture and issues said that the portrait “does not honor [Kahlo’s] legacy” and that “the mural is irrelevant and out of context of Frida Kahlo’s life and representation of her body.”

Kotis repeatedly said that he doesn’t think any of the members involved — Lewis, himself, or Bulluck — have any particular attachment to the image. So why not change it?

Clearly there are multiple people in the community who have voiced how they find the image offensive.

They say that art is in the eye of the beholder, and this is public art. We have to look at it. It’s not as if we choose to go to a museum and know what we are getting ourselves into. Critics of this article will say that we’re too sensitive or trying to censor this art. But we have a right to say when we hate something. And we hate it. Take it down or change it to something that doesn’t degrade our identities and distill us into propaganda.

We’re past being quiet about it.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Spot on! Thanks for bringing up so many powerful points!

Free speech is either free speech both ways or not at all. Art is subjective, what one person finds objective or hates is exactly the point. Weak to break it down in terms of gender, race, and sexual orientation. Stronger to discuss re-appropriation for commercial purposes. Bottom line: it was talked about, and isn’t that the goal of artifice in the first place? To be looked at, thought about, and talked about? The Frida Kahlo With A Gun mash-up mural checked all the boxes. Didn’t see a mention yet as to how the appropriation of a Rising Sun inspired background in the mural could be harmful or degrading to those who identify as Japanese or are of Japanese decent.

Exactly right. It’s ironic that at the bottom of this editorial is an ad for the First Amendment Society.

[…] in 2019, Managing Editor Sayaka Matsuoka wrote an opinion piece about how much she hated a temporary Frida Kahlo mural that went up in Greensboro. You can read the […]

[…] in 2019, Managing Editor Sayaka Matsuoka wrote an opinion piece about how much she hated a temporary Frida Kahlo mural that went up in Greensboro. You can read the […]

[…] in 2019, Managing Editor Sayaka Matsuoka wrote an opinion piece about how much she hated a temporary Frida Kahlo mural that went up in Greensboro. You can read the […]