This story was originally published by UNC Media Hub. Story by Kaitlyn Schmidt. Photography by Jailyn Neville. Video by Olivia Mundorf

In the 1973 Guilford College yearbook, The Quaker, 46 of the 235 pages were devoted to the national basketball championship win. The title page read:

“Maybe it’ll sink in next week or in a month… Maybe.”

“Maybe.”

There was toilet paper littering the campus that night, resembling Marchsnow. There were trophies, banners, a Sports Illustrated article and a letter from President Richard Nixon. The players still frame their maroon jerseys in their homes.

“When would it sink in?” team member M.L. Carr asked. “When we had time to really get away from it.”

This February, the 1973 Guilford College men’s basketball team gathered at their alma mater to celebrate their NAIA National Championship, 50 years removed from it all. But to the team, whose members bantered throughout the weekend, it felt like they were thrusting up number ones in Kansas City just yesterday.

“My 91-year-old mother told me ‘you need to go to bed so you won’t be so hyper when you get to Guilford,’” team member Robert Fulton giggled.

So, did it eventually sink in then?

Getting to know Guilford

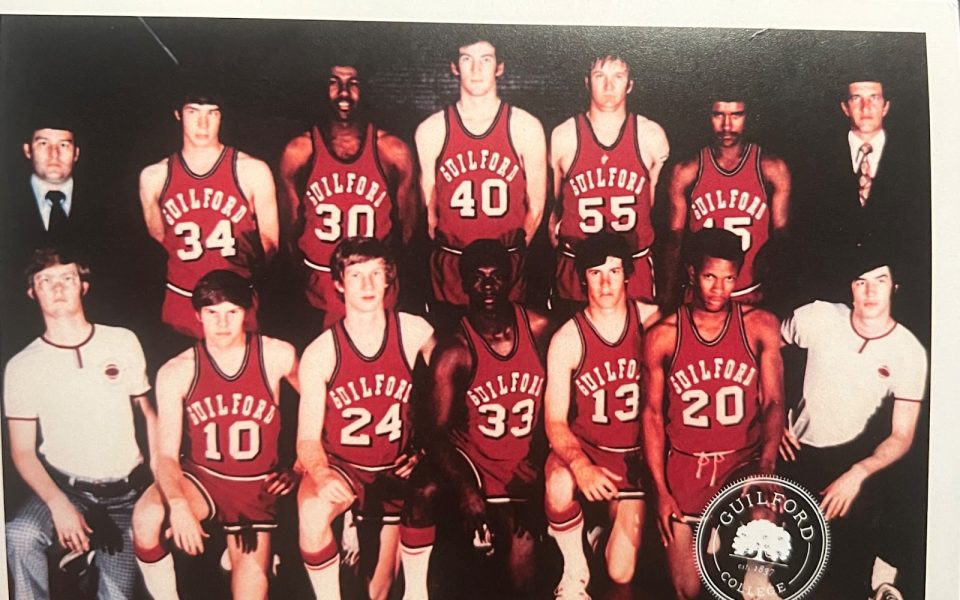

The small Quaker school tucked away in Greensboro, N.C., cultivated an odd array of talent during that 1973 season.

There were senior forwards #15 Teddy East and #30 M.L. Carr, who had unfinished business after placing fourth in the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) championship their freshman year. East was as competitive as they come, arriving on Guilford’s campus after winning the Atkins High School 4A state championship in an undefeated run during his senior year. He also donned a notable afro — which sometimes got him benched when it wasn’t trimmed.

Carr understood hard work too, after growing up getting his hands dirty in chicken plants in his hometown of Wallace, N.C. He chose the Quaker school because it offered the best education to fulfill his career dream of becoming a lawyer. Carr’s constant repetitions and focus in practice soon made him one of the team’s leading scorers, headlining his team with East until his junior year, when he tore his patellar tendon in the winter of 1972.

“As he (Carr) went out the door,” East said, as he gestured to the exit on the right side of Alumni Gym. “Our season went out the door with him.”

Finally rehabilitated for his senior 1973 campaign, Carr was looking forward to getting back into his groove and enjoying upperclassman perks, like getting his own room… But not so fast.

Head coach Jack Jensen requested that Carr room with freshman guard #20 Lloyd B. Free to show him the ropes. Learning ball on the streets of Brooklyn, N.Y., Free was distinct in his mismatched outfits and what his teammates called his “extreme confidence.” He also often stepped on veteran Carr’s playing time that season.

“Carr is willing to give up part of his game,” Jensen said. “Lloyd is the kind who can’t be happy unless he’s getting his share of the points. Even then you have to pat him on the back and tell him how much you love him and need him. Believe me, I’ve told him.”

Then there was the gentle giant sophomore #40 Ray Massengill. His 6-foot-11 stature made up for the fact that he lacked fundamentals and speed; he even admits to having a hard time even catching the basketball.

Massengill and 28-year-old Marine Corps veteran #55 Steve Hankins were both married during their championship season, taking time on their weekends for their families instead of going to shootarounds with the rest of their teammates. For Hankins, though, he didn’t get out much for other reasons.

Deployed for nine years, Hankins served on the Presidential Honor Guard and the 9th Marines — nicknamed the Walking Dead with the highest killed-in-action rate in Marine Corps history — during the Vietnam War. After playing basketball at Camp Lejeune, he chose to play a collegiate sport as a way to assimilate himself to regular life again.

“It was like a buffer for me to cool off from being where I was to fit and back into society,” Hankins said. “Because some of us belonged in a cage when we came home, we had lived like animals.”

Because of the anti-war protests at Guilford, Hankins was instructed by the athletic director to go straight from his dorm to practices, travel solely with his team and avoid busy places like the student union.

Rounding out the bunch were best friends #33 Greg “Jocko” Jackson and #13 Robert Fulton. Both juniors in 1973, their bond started as freshman year roommates. Jackson was seen as the glue of the team both on the court, as the leading point guard, and off of it, breaking up fights and being a steadying influence for the team. Fulton, on the other hand, rode the bench as a walk-on, splitting his time playing both basketball and baseball.

During the 1973 season, Fulton simply planned to be the team manager… Yet, he would get minutes in the NAIA tournament in just a few short months.

In the Crackerbox

Don’t give an inch: the team’s mantra during practices. The starting five of Jackson, Free, Carr, East and Massengill were challenged tirelessly in scrimmages. One drill involved Jensen tossing a ball into center court for two players to race toward — the guy who nabbed the ball didn’t have to run laps. This competition often caused fights.

“We’d fight upstairs, come down, take a shower, and what happened upstairs was left on the floor,” Fulton said. “There was no animosity, nothing carried to the cafeteria, nothing carried over anywhere.”

Guilford’s fiery mentality made them an exciting team to watch over the regular season, as they amassed a 19-4 record. Supporting the team’s success, students and fans formed lines outside of Alumni Gym almost two hours before tipoff to get a coveted spot in the “Crackerbox.” There was no question why the gym took on that nickname: it was standing-room only, packing in over 1,200 rowdy Guilford basketball fans.

“If someone had wanted to, they could have leaned over and untied the shoe if somebody’s throwing a ball in bounds,” Danny Chilton, Guilford class of 1974 graduate, said. “So it was a little snake pit.”

The season’s high came to a halt when the Quakers fell to Catawba in the Carolinas Conference Tournament — its third consecutive conference championship loss. For upperclassmen Carr, East, Fulton and Jackson, the second place trophy only lit their competitive fire. And the season was far from over.

Two days later, Guilford beat Barber-Scotia and then Winston-Salem State to represent District 26 in the NAIA tournament. That sealed Guilford’s postseason fate: the Quakers were going to the tournament for the fifth time in eight years.

With the campus engulfed in student mobs, toilet paper and blaring car radios, Jensen responded to a “speech!” cry in Quaker Square.

“We are going to work real hard now for the national tournament,” Jensen said, who had been hoisted up on shoulders in the crowd. “We are going out there to win it all.”

Good ‘ole Kansas City

The flight on Saturday, March 10, to Kansas City was Fulton’s first time on a plane, and Massengill’s first time out of North Carolina.

And the team wasn’t alone — about 50 fans made the trip, most of them students who hitchhiked to Missouri, slept on the floor of shared hotel rooms and bummed off of each other for food.

In the early hours of Monday morning, the first day of the tournament, Jensen took his team for a half-mile walk through the chilly downtown. For some, it was beneficial to loosen up their bodies and nerves. For others, it helped them be present for the opportunity at hand. That walk soon became a tournament ritual.

“We got a little sightseeing in and there was togetherness,” Carr said. “So when we came on the floor, there was a bond beyond the actual play.”

That unity was evident in Guilford’s first round matchup versus Keene State that afternoon. The Quakers dominated by 26 points at half, leading so comfortably that subs like Fulton played for most of the second half. Only when the Owls cut the lead to 10 did Jensen call the reserve players out of the game — and the Quakers won 91-81.

Guilford took on three more games in the span of three days. In the second round game against Valdosta State, guards Jackson and Free combined for 27 points in the second period and lifted the Quakers to a 17-point win, 98-81.

Guilford’s motley crew continued to defy expectations during the next two rounds. Against Wesmont on Thursday, the Quakers scraped by with a 70-67 win that was largely thanks to Guilford’s14-for-14from the foul line. Free put up 25 in the final four game against Augustana and Massengill locked down the paint on Friday to blow out the Vikings, 77-69. And yet, another win meant that they’d have to do it all over again the next day.

Boy, were they tired by that national championship game.

Just a pack of mixed breed underdogs

Even after besting their tournament opponents by an average of 9.5 points, unseeded Guilford was still the undisputed underdog in its National Championship matchup on Saturday against No. 8 seeded Maryland Eastern Shore. The team with the ex-marine, married man, boy with an afro and player with mismatched socks was underestimated. But this status worked to Guilford’s advantage every time.

The players took one last walk in Kansas City that morning before taking the court in the Municipal Auditorium. The arena was eerily quiet — there were only about 100 fans between the two schools in the stands. But that didn’t mean those rowdy Quaker fans weren’t listening at home.

The parking lot next to Binford Hall on Guilford’s campus was loaded with cars; it was a place off the highway where students got the station signal to tune into the national championship. Chilton and his girlfriend Linda Barnes had driven an hour from Surry County to listen in, leaning forward in the black leather seats of his Chevy II Nova to take in every moment of the game.

Guilford was in an offensive rut early, down nine points when Jensen called a timeout at 8:48 in the first. In the middle of the huddle, the all-too-confident freshman piped up.

“Y’all give me the ball,” Free said. “And I’ll take care of things.”

And take care of things he did. Free scored the final shot in the first half to notch Guilford up by two, 48-46, then personally gave the Quakers a 57-50 lead in the first three minutes of the second period. Later in that half, Free even cockily stole the ball, and on a break, did a 360-degree spin move and drew a foul on his way up for a three-point play.

“Who would even think of doing a 360?” Carr laughed. “That’s a playground move!”

With East’s nine steals and roommates Free and Carr’s combined 63 points in the game, Guilford commanded the lead for the rest of regulation. A shot by East with six seconds left brought the Quakers out of reach, and Guilford won the game 99-96.

After the buzzer sounded, Guilford fans around the stadium triumphantly thrust their pointer fingers up in the air. The banner was revealed, nets were cut and the trophy was presented to the team. Seniors Carr and East shared the weight of the hefty Naismith award, beaming at each other.

“The greatest thing in the world is number one,” Carr said. “Being the first national championship team for Guilford College, you never take that away.”

Meanwhile in that small on-campus parking lot, car horns trumpeted, high-fives and hugs were exchanged and trunks filled with toilet paper were plundered. In a flurry of white and “we’re number one” chants, the Guilford College campus partied through the night.

“I was afraid that if I went to sleep,” one fan said. “I would wake up and find it was only a dream.”

When it finally sunk in

The team parted ways after their Guilford careers, though they still kept in touch. East became a probation officer in Winston-Salem, Hankins coached basketball at North Carolina high schools, and Fulton remained at Guilford to coach baseball from 1985-97.

Jackson was drafted in 1974 by the New York Knicks and played a year in the NBA before retiring and becoming a community leader in his hometown of Brooklyn. Free played a fruitful 14 years in the NBA as the 23rd overall pick of the 1975 draft. In 1981, Free legally changed his first name to “World,” as his hometown friends nicknamed him the “all-world” player. Of course, he obliged.

Instead of fulfilling his dream of attending law school, Carr played pro ball for 12 years, notably with the Detroit Pistons and the Boston Celtics — the franchise that he won the 1981 and 1984 NBA Championships with.

After claiming the 1984 title over the Los Angeles Lakers, Carr was asked if it was the greatest feeling he had ever had in the sport.

“No, it mirrors the best feeling I’ve ever had in the sport,” Carr responded. “My 1973 Guilford College National Championship was big. It may not be bigger than the ‘84 championship against the Lakers, it was just as big. And why?”

“We were unseeded. We were unranked. But when we left the gym in Kansas City, we was ranked.”

Now, half a century after their win, Fulton still saves his luggage tags from his first flights and Hankins keeps his water-stained copy of the Sports Illustrated article about the team, Underdogs Steal the Bone.

As the bunch gathered back inside the Crackerbox in February to rehash the good ‘ole days, they thumbed through old scorebooks and pictures, running their calloused hands over the faded gold plate on the Naismith trophy. In a big pod, the team strolled around the brisk campus of their alma mater exchanging memories, reminiscent of their Kansas City walks.

The last time they had all reunited at Guilford was 13 years ago, when Jensen died. The court in Ragan-Brown Field House was named after him during Basketball Legacy Weekend in 2009; Free and Carr’s jerseys were also retired and hung up then.

In 2012, Jackson died unexpectedly, and some of the team members made the trip up to New York for his funeral and the naming of a Brooklyn school in his memory, the Gregory Jocko Jackson School of Sports, Art and Technology. Each time Fulton mentioned his best friend at the reunion, he sputtered and tears welled in his blue eyes.

“There is a bond that’s been built among that ‘73 team,” Carr said. “At our age, how many times are you gonna get the chance to do this?”

At the banquet on the evening of February 17, the team — minus Free, who did not attend — was honored in front of their wives, children, alumni and the new generation of Guilford men’s and women’s basketball.

“These guys that play today don’t know anything about Free or Carr, we’re all old men,” Fulton said. “It would be like the 1923 team had a reunion when we were playing. It doesn’t mean a whole lot, except what it means to us.”

Through the dinner, drinks and sentimental open-mic speeches, members of that ragtag team 50 years ago experienced the comradery of the national championship run all over again. Thus, 50 years later, did it sink in?

Why, yes. Yes it did.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply