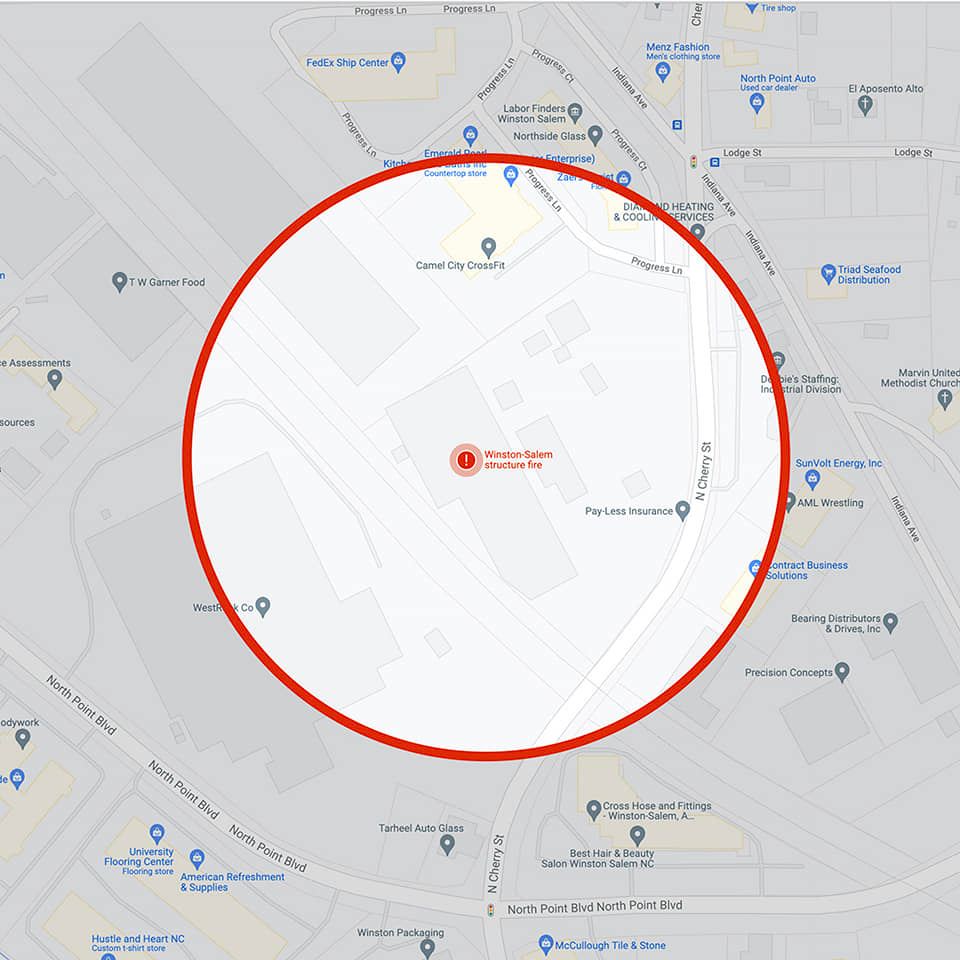

Featured photo: The majority of people in the Weaver Fertilizer blast zone were Winston-Salem’s Black and Brown working class. They were already hurting when a disaster that they never asked for forced them from their homes (photo by Chad Nance)

Tomeaka George

There are cracks in the foundation of the three-room, wood-frame house. The rats come and go as they please, as they are wont to do. What heat Tomeaka George is able to generate from running an open stove along with a noxious kerosene heater flows freely through the cracks and leaches through the thin walls of their house on Melody Lane.

George shares the house with Mom, a double amputee and stroke survivor who spent a lifetime working in a meat-processing plant, which provides her “retirement” with only a modest stipend and government assistance. She works at a local hotel cleaning rooms, but makes the trip back to her house three times a day in order to make sure that her mother is fed, gets to the bathroom and stays clean. Also in the home is Mom’s elderly brother, who needs near-constant care himself, and two of George’s daughters.

It is Jan. 31. There are still piles of frozen snow on the ground; the air inside of George’s house bites with the same vicious determination as the air outside.

She hears the sirens first. They cut through the usual street and industrial noises that bleed into the house. Next she hears the amplified voice of a Winston-Salem firefighter telling her to evacuate her home immediately. No explanation. Just get the hell out and do it fast.

Red lights splash through the front windows as the sounds of the siren and the voice grow more insistent. With her daughter’s help they are able to get Uncle dressed for the outside and Mom into her wheelchair. George doesn’t have a car right now and she has no extra money — not after she just paid the rent. Before she even pushes Mom out into the frigid air, George knows that if they are going to get away from here, they will be doing it on foot. Huddled together in the cold they all begin to walk. Three houses up Melody Lane runs into Cherry Street. One block away from the Weaver Fertilizer plant.

Breathing is difficult from the jump. Tomeaka has everyone put on masks, but the noxious smoke works its way into their noses, their eyes. It burns the skin. When they reach the corner of Melody and Cherry Street, all Tomeaka can see of the fertilizer plant is the angry orange glow of the fire and a dark, billowing column of smoke that stretches into the air like something out of the Old Testament.

Mom starts to scream while fear grips all of them. Tomeaka tries to keep her own fear under control and somehow calm the others. She knows that they have to get away, but how far is safe and how are they going to do this in the cold, through the smoke, on foot pushing Mom in a wheelchair? Tomeaka does exactly what Tomeaka has had to do all of her life.

“I put my trust in the Lord and we just started walking away as fast as we could,” she recalls, “and I tried not to look back.

Brandon and Xzavier Brown

It is 3 a.m. when Brandon and Xzavier Brown hear the fire trucks outside of their brick ranch house on Delmonte Drive, just off of Polo Road. More red lights, this time coloring broad, well kept lawns. The the fireman calls out his warning through the speaker.

The Browns are a hard-working couple with six young children. He’s an Amazon delivery driver. It is impossible for her to work full time with six children, but she takes third shift work from time to time then sleeps whenever she’s able. The brutal realities of the COVID-19 pandemic have been both economic and health related for this family — Xzavier has had the virus three times and the whole family had it earlier in January.

Between kids and work they don’t get online very much and hadn’t gotten word that the Weaver fertilizer plant is engulfed in flames and smoke. They have no idea that more than 6,000 people in a 1-mile radius from the plant need to evacuate their homes immediately. Most importantly, they haven’t heard that there are enough dangerous chemical compounds at the plant in quantities that, if mishandled, could cause the largest land-based explosion in United States history since the Nevada desert nuclear test of the 1950s.

Brandon and Xzavier don’t know that the same kind of chemicals that flattened West, Texas and tore through the Beirut waterfront with apocalyptic fury are located less than a mile from their house, in a plant that had already had one fire in the last month. What they do understand at this moment is that they have to gather their children and they have to get out. Neither one of them has ever seen or heard of fire trucks coming through the neighborhood with a warning like this, and they take it seriously. Both can smell the smoke and taste the chemicals. Xzavier thinks about her children breathing in the smoke, and is sure of only one thing. They have to flee.

The young couple manage to get all of the kids out of the house. They make sure that all of the kids have masks against the acrid smoke. Somehow they get all six kids, including the baby, into the car. Everyone is in pajamas; they don’t take anything with them beside their IDs. One thing they definitely didn’t have was cash. Even though they have work, money is tight. It’s the end of the month and they just struggled to pay all of their bills. There is absolutely no money for a hotel room and no relatives locally who could take them in. They drive around the city for a while, then they park in an empty parking lot to try to stay warm and figure out what has happened. Their entire family of eight is out of the blast zone…. Now what?

Shelby Wilson and Giovanni Reynoso

When Shelby Wilson first hears the knock at the hotel door she thinks that it must be the clerk, finally telling them they have to get out. Her husband Giovanni Reynoso is working, but it isn’t nearly enough and they haven’t been able to pay for the room. With six kids and one on the way, just feeding the family every day is an uncertainty. Shelby is awake when the police officer knocks because she can’t sleep with this worry weighing her down.

Wilson is a small-town girl from Tennessee, but Reynoso has family in Winston-Salem. Before the pandemic Reynoso had a good job, they had a vehicle and they had a roof over their heads. The arbitrary cruelty of the pandemic took all of that away — first the car then the house. Relatives were struggling themselves, so taking in the couple with their six kids and one on the way simply wasn’t an option. Now the man is at their door and the rent is way past due.

As soon as Reynoso opens the door smoke begins to slither into the room. Even as the officer is telling them that they have to flee, Wilson begins to gather up the children. She can smell the smoke. It burns her nose. What’s it doing to the baby? Jesus, she doesn’t even know yet if it’s a boy or girl.

Reynoso rides in the passenger’s seat of a Winston-Salem police cruiser. Two of his little ones are in the back seat. Wilson is in a cruiser in front of them with the other kids. As they pull out of the parking lot Wilson can see up Northwest to Cherry Street, where the whole world seems to be ablaze. The horizon glows orange and red while the column of black, poison smoke looms over her and their family as officers drive them out of the blast zone.

They came to Winston-Salem hoping things would be better.

Families who were already hurting

Tomeaka and her family were walking away from the blaze when they were picked up by a Winston-Salem police officer. He gave them $50 to get a hotel room for the night. Even with that, she couldn’t afford a room so the officer took them to the American Red Cross shelter in the process of being set up at the Lawrence Joel Coliseum Annex. There were no cots yet, no steaming trays of food and emergency blankets like the television commercials. This disaster came with no warning and there was no time to get those things in place. What they did have were some folding tables and chairs.

Shelby, Giovanni and their children were already there. No toys, no electronic gadgets, no options but to sit down in plastic chairs and try their best to keep themselves quiet. Their children ran across the wide open concrete expanse of the empty annex trying to burn off energy while the adults huddled around tables trying to process what had just happened to them.

Brandon and Xavier hadn’t found out about the emergency shelter yet. They were still sitting in their SUV with the engine running to keep warm and their six children trying to be comfortable in the back.

It would be four days before rain and the Winston-Salem Fire Department were able to get the blaze under control, to ensure that a massive chemical explosion wouldn’t rip a hole in Winston-Salem flattening houses, killing thousands and sending a shockwave miles beyond the initial blast site at Weaver Fertilizer.

Thousands of human beings just like Tomeaka, Xzavier, Shelby and their families would be displaced for days, depleting funds that they didn’t have in the first place on hotel rooms, meals, and basic necessities. Money they would never have had to spend if this hadn’t occurred. Thousands more were forced by economic circumstances to go back to their homes before it was remotely safe. They lived with the threat of violent death and in the cloud of poison smoke for days because they simply had no options — none that were communicated to them, anyway. The shelter provided had no facilities for showers, privacy or personal space for belongings, no way to stay safe from the virus that continues to ravage our community.

The majority of people in the Weaver Fertilizer blast zone were Winston-Salem’s Black and Brown working class. They were already hurting when a disaster that they never asked for forced them from their homes and to spend resources that were already stretched to their thinnest, all during a historical pandemic that also disproportionately affects their communities.

Just because the fire is out and residents can go back home does not mean the trauma and risk are over. The Weaver Fertilizer fire has simply alerted the broader community to the struggles and risk their neighbors inside of the blast zone live with every day.

Donations and requests for assistance can be made at: loveoutloudws.com/relief.

Those living in the area can call a new toxicology hotline that has been established by the city at 866-412-7768.

Evacuees displaced by the plant fire can call 336-747-3067 to be reimbursed for hotel stays. They’ll need to show proof of residency and hotel receipts.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply