On the sixth floor of the Wake Forest University Library, a treasure trove hides among the stacks collected in 34 nondescript boxes.

The Harold TP Hayes papers are a compendium of letters, notes, photographs, recorded and transcribed interviews, manuscripts, galley proofs and other pieces pertaining to the life of perhaps the greatest editor in the history of the business.

Hayes was editor of Esquire magazine during its finest years, when it served as a platform for what would become a new kind of journalism. Any serious student of nonfiction has read the writers who toiled under his watch: Gay Talese, Tom Wolfe, Gloria Steinem, Norman Mailer, Nora Ephron and the like.

But he was born and raised in Elkin, NC about an hour outside of Winston-Salem. And before he moved to New York and embarked on his literary career, he graduated from Wake Forest in 1948, back when the school was actually in Wake Forest.

After his death in 1989, his body of work found its way to his alma mater. I found out about it when I saw a documentary about Hayes, Smiling Through the Apocalypse, made by his son Tom that plumbed the contents of the collection, at RiverRun in 2013.

I haven’t stopped thinking about it since.

Hayes presided over the most significant era in journalism since the telephone, when reporters began using the same techniques as novelists — dialogue, metaphor, storyline, style — to write their features. That’s when journalists started writing.

***

It’s a story I know by heart.

It’s a story I know by heart.

In the late 1950s, Esquire magazine had turned to pulp. The 20-year-old men’s literary institution once ran commentary, fiction and features by the likes of Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. But it had veered more towards content appealing to the lowest common denominator: pin-ups, war stories and true crime.

By 1956, Hayes had finished a stint in the Marines, worked for United Press in Atlanta and moved to New York City to work in magazines. That year Esquire’s founding publisher Arnold Gingrich hired him as an assistant.

It was the Golden Age of the American magazine. Postwar affluence and a rapidly developing American culture gave fodder to the medium, more sophisticated than a newspaper, more intimate than the burgeoning medium of television, more satisfying than film. And Esquire was asserting itself as a major player in the game.

By the end of the decade, Gingrich would take on two other noteworthy assistants. One, Hugh Hefner, would abscond to Chicago with the more salacious threads of the old Esquire and weave them into Playboy. The other, Clay Felker, would become Hayes’ rival for control of the magazine.

By 1962, Gingrich was 59 and had been at the helm of Esquire for 29 years. And both Hayes and Felker had designs on his position.

The old man perpetuated the competition, playing the men off each other in what must have been a fascinating intra-office drama. Hayes would come out the winner, named managing editor of the book that year, while Felker spun off to start the Sunday supplement for the New York Herald, recruiting writers such as Tom Wolfe, Jimmy Breslin, Gloria Steinem and Adam Smith to carry the flag. The freebie supplement would eventually become New York magazine, still the best weekly in the business.

Hayes worked his own desk, putting out the kind of magazine writing still analyzed in journalism schools and creative nonfiction classes today.

But in truth, nobody won this competition for the top chair at Esquire. Hayes hung on as managing editor and editor but would never be publisher He left in 1973. Felker actually bought the magazine in 1977 but sold it two years later after a failed attempt to turn it into a “fortnightly.”

Hayes took a few turns on television and did some writing — most memorably a series for Life magazine about animal researcher Dianne Fossey that would become the film Gorillas in the Mist.

His contribution to the new journalism, however, lives forever in those boxes on the sixth floor.

***

The writer Gay Talese spent most of 1965 chasing down Frank Sinatra so he could file a profile for Esquire under Hayes’ editorship.

After a few years of boozy irrelevance, Sinatra was becoming hot again. Talese, fellow Italian-American from the New York area, thought he might be able to pin down the man with a long-form profile.

Trouble was, Sinatra was being kind of a dick about it.

He ditched interviews, had his goons run interference, hid behind velvet ropes and closed doors. Talese was getting frustrated, and in November he typed a letter to his editor from Los Angeles asking for guidance.

“Yesterday I saw Frank Sinatra very briefly. He did not have time to talk — he never seems to have time….

“The disappointments and long wait of this assignment are frustrating, but perhaps we’re making progress. Frank S did allow me (with a half-dozen other of his followers) to accompany him to his dressing room yesterday and he was unself-conscious enough to remove his toupee in my presence.

“The money is holding out… because I am charging things to this hotel bill. I checked around at other hotels and apartments, and the savings would not, I think, be that substantial. Everything is expensive in this goddamned place…. It’s a real gamble, I realize, and yet I have a feeling things will work out. I might not get the piece we’d hoped for — the real Frank Sinatra — … but perhaps, by not getting it — and by getting rejected constantly and by seeing his flunkies protecting his flanks — we will be getting close to the truth about the man.”

The piece, “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” ran in the April 1966 edition of Esquire. It remains one of the most important pieces of journalism in the last 100 years.

***

Hayes’ letters include hundred of missives like this: editorial wranglings between writers and sources, personal words of encouragement, negotiations, criticisms and the deflections thereof.

In April 1965, he turned down a long-form essay about St. Louis by celebrated Beat writer William S. Burroughs, saying, “[I]t’s a mite incoherent for us, I’m afraid. We’ll have to pass up the opportunity of buying it.”

In 1966 he critiqued a piece by Peter Bogdanovich, who at the time was a film critic but would two years later turn to directing and, in 1971, make The Last Picture Show, a coming-of-age masterpiece set in a small Texas town that would be nominated for eight Academy Awards and win two of them.

But in 1966, he was just another journo taking guff from his editor.

“Well, I think this is vastly improved — at least 35% better than it was. But I still can’t use it. Because I do not relish the idea of being called at home and chewed out, let me set forth my reason for this reaction as succinctly as possible: the rendering of Sonny and Cher as apt representatives of teenage fantasy, and the concordant revelation that their own personal existence is a state of near vacuity, insufficiently progress our editorial coverage in this area….”

That same year, Hayes offered the novelist Thomas Pynchon an experimental column seven years before Pynchon would publish his first masterpiece, Gravity’s Rainbow. Pynchon did not get the gig. Hayes wrote:

“All of us felt it was strong and thoughtful, and very close to what we are after. As I mentioned, I believe, I had asked several other writers to try too, and our choice has come down to Wilfrid Sheed.”

I’d never heard of Wilfrid Sheed, but he would win a National Book Award the next year, in 1967. His only other award came 20 years later, a Grammy for the liner notes on the album The Voice – The Columbia Years 1943-1952 by none other than Frank Sinatra.

The photographer Diane Arbus, before her suicide in 1971, earned her reputation by shooting “marginal” people — transgender folks, circus freaks and others on the cultural fringe.

In the 1950s she endeavored to shoot the inmates of a women’s prison in New York City for Esquire. An official from the NY Department of Corrections told her she would have to make a “donation” of at least $50 — “CBS gave us $350” he told her — in order to gain access.

When Hayes got wind of it he wrote the official directly in characteristic prose:

“[Y]our organization is the first one in the city in which we have encountered such a proposal in subjects which we assume to be open and of concern to the general public….

“Therefore we are unable to meet with your requirements, and I wonder if this is really a proper reason for your exclusion of us.”

When Hayes dispatched Arbus to shoot Joan Crawford, the notoriously difficult actress declared that she had never heard of Arbus. An Esquire secretary wrote, “Personally I wonder if the great Miss Crawford might not scare the living daylights out of Miss Arbus,” and suggested a more traditional fashion photog for the shoot. Hayes remained true to his vision in his reply.

“Nix. Call Arbus and find out what she’s published in Fashion Mags, get tearsheets and send to Crawford.”

A few months later, he revisited the subject with Arbus.

“[L]et Crawford go,” Hayes wrote in a short note. “Will get someone else.”

In one of her final pieces of correspondence, Hayes sent her a tiny newspaper horoscope clipping affixed to his personal notepaper.

It reads: “Those who hold the reins have the advantage and you resent it. Your turn will come. Just be patient.”

The Tom Wolfe folder teems with back-and-forths, Hayes’ typed on Esquire letterhead, Wolfe’s quite often handwritten in ink-dipped calligraphy.

It was in 1963, under Hayes’ editorship, that Wolfe took on an assignment to write about the new phenomenon of custom cars. Crippled by writer’s block, he compiled his wild and fanciful notes — with lots of italics, odd::::: punctuation and random exclamations! — and submitted what would become “The kandy-kolored tangerine-flake streamline baby,” one of the very first published pieces of new journalism.

But it was another piece, “Post-orbital remorse,” for another magazine, Rolling Stone, that elicited the highest praise from Hayes.

“Post-orbital remorse,” about the depression astronauts felt after returning to Earth, eventually became the book The Right Stuff in 1979; a film version came out in 1983.

Hayes took an edit of the book before it went to print, and was clearly blown away:

“I really can’t tell you how impressed and admiring I am of what you are doing with this. I expect anything you do to be distinctive, original and compelling but with this you have a theme (many themes!) that touches the lives of everyone, gives them a priceless perception and understanding of the history of their time — and all with whatever artistic skills this terribly complex world requires for us to understand. I am just terribly proud of you.”

I can tell you: Editors rarely talk like that.

His connection to his writers was legendary, but one letter in his files testifies to it directly.

The writer Nora Ephron worked at Esquire in 1973, when Hayes lost his job. She was then a young journalist but would go on to write, among other things, the essay collection Wallflower at the Orgy, the novel Heartburn and screenplays for When Harry Met Sally, Sleepless in Seattle and Julie & Julia.

In a note typed on pink paper, she wrote to her favorite editor:

“I have had two months here, and I have loved it, largely because of you, and I’m not talking about how much fun you are, or how cute, or any of that, but about… the goading you mentioned at lunch, how extraordinary it is to watch you pull out of people what they didn’t know they could do.”

He saved his most effusive charm for Dorothy Parker, the onetime denizen of the Algonquin Round Table and America’s foremost woman of letters of the 20th Century.

By 1957, the year of Parker’s letter to Hayes — written in loopy, schoolgirl script — she was 64, had been blacklisted in Los Angeles for her perceived communist leanings and was living and drinking in an apartment on the Upper East Side. She wanted to write book reviews, and the first one, it seems, went well. Hayes delicately asked her to cut 31 lines from it.

By 1959, however, the doyenne was having trouble making deadlines.

In November 1959, Hayes wrote to thank her for allowing him to visit her home and for the “elegant bottle opener.” He went on to say:

“I didn’t have the nerve to say that your column is due next week. Outside the hospitality of your home now and only slightly less cowardly, I find the production editor more formidable than, last evening, I ever would have suspected. Is this coming Monday too much of a drag?”

Jan. 2, 1962:

“Your piece never came and there is a good possibility that I will be strung up by the thumbs by the accounting department unless I can get you back in the magazine forthwith.”

May 14, 1962:

“We need a column by Wednesday the 23rd. Would you write it to us and send it to us this time? We will be willing to take dictation over the phone indefinitely rather than not have it at all. But this is bound to be wearing on you. And even if this is not the case, I fear the column suffers too much. As you know, we tend to garble your meaning and sabotage your phrases, neither of which occurs when you are able to send us a manuscript.”

Sept. 4, 1962:

“The enemy is at the gate. I’ve been forced in recent weeks to an agonizing reappraisal of the inventory and discover that we’ve paid you roughly 5,000 bucks for columns we haven’t received.”

Oct. 22, 1962:

“I checked immediately on our payments to you in order to see if we had fouled up in some way…. I told them you had failed to receive checks for the months of September and August. They are unable to account for this discrepancy since they have received your cancellations of these checks from the bank for these two months. The only thing this can point to is robbery or forgery in the mail room, which I hope to Christ isn’t the case.”

March 8, 1963:

“Guess what, by God! Management has got to the point of missing you so sorely they are holding me responsible for your absence….

“They asked me then what could we do? Send her $750, I said hopefully, to convince her how much we want her back.

“And they agreed. Your check will arrive within a week or so, no strings attached. How about that! And if you just get me one column — just one… I can send you another.”

Aug. 28, 1963:

“The check went out yesterday….. To facilitate this, I delivered to our Accounting Department seven pounds of my flesh. They will return it if I get a column from you in two weeks. Don’t worry unduly about this since I am slightly overweight.”

Based on this exchange alone, Hayes is the greatest editor in the world.

***

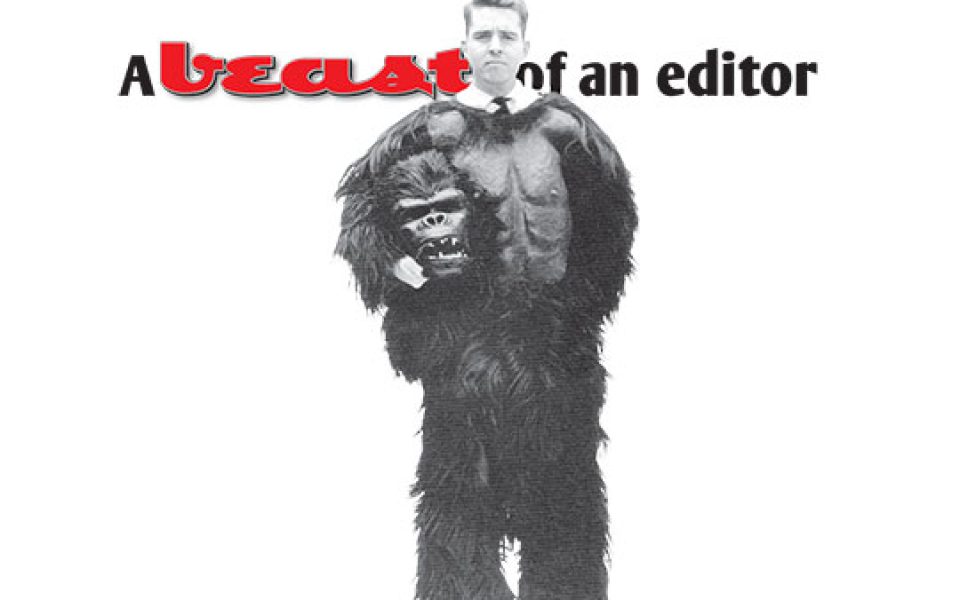

Hayes was widely regarded as charming and genteel in the New York magazine world of his day, with crisp, oiled hair, fitted suits and taps on his shoes that assistants said echoed in the halls as he paced the offices on Madison Avenue.

His gentility comes through in another exchange, with the noted conservative journalist William F. Buckley, who in 1965 was the young founding editor of National Review.

Buckley had heard Esquire was intending to run a piece about Ronald Reagan, whose film career had just about ended but whose political star was beginning to rise. Buckley took issue with the journo assigned to write the story.

“I find it inconceivable that Jessica Mitford should have been given this assignment considering a record of undeviating loyalty to Communist causes, and her presumed loyalty to her own husband, the Communist Mr. Truehaft.”

Hayes replied:

“I’m sure you know how highly I respect your opinions and your commitment to them, but I find it difficult to see as my responsibility the prejudgment of Mitford’s piece on the basis of her reputation.”

Even better was their civilized row over a piece Buckley had written for Esquire in 1966. At issue was a footnote that Buckley said had been tacked onto the end of his article as a kicker. Buckley opened:

“Dear Harold: I love you like a brother. But it ever it happens again, I shall have to come to your office with my shooting iron and blast away in the cause of editorial integrity.”

Hayes replied:

“Dear Bill, As the old company commander of one of my old company commanders used to say back in the Civil War, ‘Plenty of excuses but no reasons.’…

“Lamely but gamely I accept 97% responsibility. The other 3% is yours. Kindly look again at your original.”

Buckley had not labeled his footnote correctly, using “#” instead of “*.”

“I am, as usual, overcome by your charm. But more than that, having seen my original manuscript, I think it plain becomes 97 per cent mine and only 3 per cent yours,” Buckley responded.

Later, Esquire would become Ground Zero for Buckley’s verbal — and legal — war against Gore Vidal. On the strength of one of Vidal’s essays for the magazine, Buckley sued Esquire for libel in 1969.

The Norman Mailer file includes several legal documents.

Mailer was at the top of the literary world in 1964, when Hayes serialized his novel An American Dream in its pages. But letters show he had been a difficult writer as far back as 1959, when he insisted his story, “The mind of an outlaw,” and his name get “top billing” on the cover of the magazine.

In 1962, Hayes tapped him for a monthly column. Mailer’s contract, drawn by his lawyers at Rembar & Zolotar, included the clause “You will have the right to reject any column for reasons of policy. A rejection of any part of a column will constitute a rejection of an entire column.”

Mailer sued the magazine in 1972 over use of his name as a contributor.

***

The Hayes papers are a time capsule of the era: carbon-paper copies of typewritten notes on business letterhead and personal stationery. There are telegrams — I’d never before seen one — and wires, messages long since irrelevant handwritten on notepaper, penciled manuscripts and galley proofs.

A handwritten note from Salvador Dali with instructions, in French, on where to send the check. A letter from the wife of Ernest Hemingway, written on her personal stationery with her New York address on the envelope. Letters from Charles Kuralt, Ring Lardner, Groucho Marx, Hubert Humphrey, Richard Nixon, Saul Bellow. Threats from Timothy Leary. A mash note to Truman Capote. It’s a trove of insight into the great minds of the time, likely never to be repeated. I wonder what we’ve lost in the digitization of our communications. There is no modern-day equivalent to the letter sent to Hayes by James Baldwin in 1966.

Their relationship on file dates back to 1959, when Hayes tapped Baldwin, then an expatriate living in Europe, to write pieces about Charlie Chaplin and Ingmar Bergman.

He never tracked down Chaplin, but “The precarious vogue of Ingmar Bergman” ran in April 1960.

Baldwin and Hayes got into an infamous beef in 1962, after Baldwin’s piece, “Harlem for fun,” did not match the art Hayes had planned for the issue. Hayes tapped Gay Talese to turn something around, and Baldwin was furious.

It would be four more years before Baldwin would issue his apologia, handwritten in scrawling black to “My dear Harold Hayes.” Baldwin used capital A’s in his handwriting:

“I hope you’ll read this in the way it was meant. I’m writing you to clear my conscience. I think, now — have thought for some time, in fact, but did not know how to tell you — that I over-reacted to the Esquire article. I detested it, and I probably always will. I may be wrong or right about that, but the point of this note is today that I think I was extremely unjust to you, and I have long regretted it, and I profoundly hope that you will accept this lame and too-long delayed apology. I have much respect and affection for you, and that’s the truth and life’s much too short for one to allow oneself to be as petty as I think I’ve been.”

For a note from a writer to an editor, it’s startlingly personal.

Another note gains significance with backstory.

By May 1973, Hayes had left Esquire when Gingrich passed him over for the publisher’s position. His rival Clay Felker was riding high on the success of New York magazine while Hayes floundered for work.

The lone item in the Felker file is a single note, on Hayes’ personal stationary, addressed to Felker and hand-delivered to his apartment on East 54th Street. In it, Hayes thanks Felker for hiring him for something called “The Watergate Paper,” and paying him $3,000 to undertake the project. He closes humbly:

“I am grateful for your enthusiasm about all this.”

The project would never be published, its only historical reference point tucked away on the sixth floor of the Wake Forest library.

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Brian, your article made Harold’s family very proud and happy. My daughter first saw it in Greensboro this week and Tom Hayes sent it to us, also.

Phyllis Hayes Johnson (Harold’s sister)

Tega Cay, SC

Thanks so much, Phyllis. I had more fun writing that one than I’ve had in a while. That whole era of journalism changed my life.

Helluva story, man. Amazing to know such snapshots of time are right here in our community.