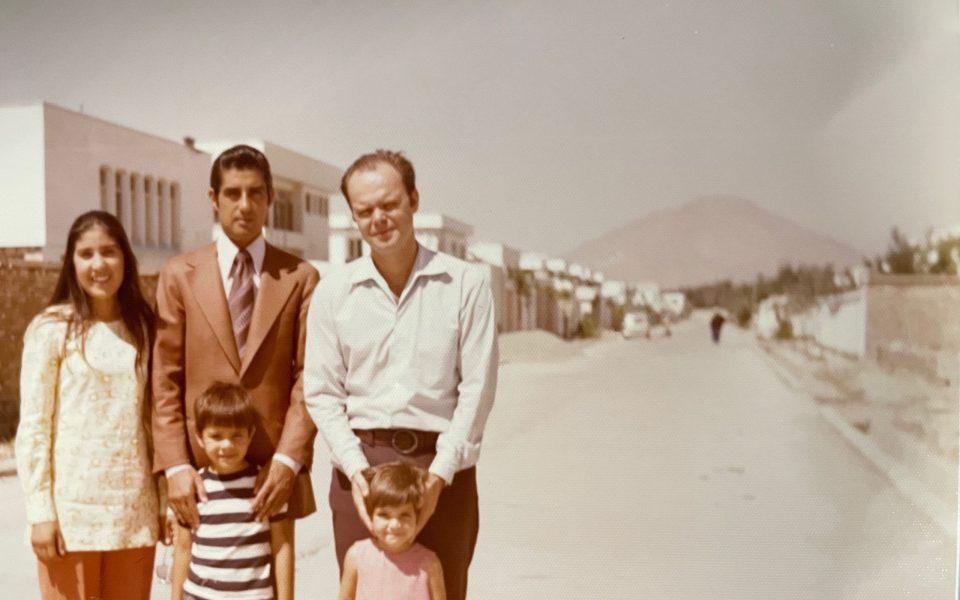

Featured photo: Mariam Stephan’s family circa 1975. (courtesy photo)

Mustafa Rashid, Greensboro, 43

Mustafa Rashid was utterly unprepared for 9/11. A college student at the time, he was confused, angry and, most of all, ashamed for being Afghani.

“I had all these emotions,” he said. “But a few months after that, I went to an Afghani wedding in New York. And seeing them at this wedding, I’m sure they got it 100 times worse than I did living in New York City, but they were still proud of who they were.”

In his lifetime, Mustafa has gone through the gambit of emotions about his Afghani heritage. His father, Said Rashid, is from Afghanistan, but Mustafa was born in Japan, where his mother is from. Mustafa has never been to Afghanistan.

His parents met in the 1980s, after Said fled Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation and decided to attend college in Japan. Said worked in maintenance before going into engineering.

The Soviet occupation began in 1979, and by 1980, the Soviet Union had sent thousands of troops into Afghanistan, assuming control of the capital, Kabul. The invasion was a strategic move by the Soviets as part of the Cold War, which was going strong at the time.

During that time, then-president Ronald Reagan secretly armed the Mujahideen, or holy warriors, in Afghanistan to combat Soviet influence.

“There’s a lot of people who played a role in this, and the US has played a huge role in the days since the Soviet War,” said Mustafa. “Afghanistan didn’t have a ton of money at that time, and the US haphazardly dumped all this money into Afghanistan and didn’t handle corruption. I think that’s the biggest issue over there.”

Mustafa’s family came to the US a little more than 30 years ago, to be closer to Said’s family. Mustafa’s mother didn’t have any family here, so Mustafa grew up mostly around his Afghani cousins.

“All of my aunts and uncles and cousins, we all moved to Greensboro originally,” Mustafa said. “It was a pretty big community for a while for Afghans fleeing the war. A lot of people I knew have since moved on to [Washington] DC or California, but for a while there was a strong community.”

Mustafa’s father has been back to Afghanistan just once since then, about 10 years ago. He went searching for his parents’ graves and was unable to find them due to the ongoing wars.

The most recent upheaval in Afghanistan has left Mustafa and his family feeling uncertain and hopeless, especially for Mustafa’s aunts for whom it is difficult to process what their home country has become. Said’s cousin still lives in Afghanistan.

“It didn’t have to be this way,” Mustafa said. “I know the Afghan people. They’re very proud people. They’re warm. They’re the type of people that even if they don’t have any money, they’ll invite you for dinner. They’ll go out of their way to provide for you as a guest. When I see people going through what they’re going through now, I can’t help but picture the people I know.”

Tahe Zalal, Greensboro, 46

Decades before the Soviet invasion, AG Zalal, who is from Kandahar in Afghanistan, met his wife, a North Carolina native, who was working for the state department.

“They met and dated, and then got married,” said AG’s daughter, Tahe Zalal. “Back in the ’60s and really up until the Soviet Invasion, women and men could socialize and go to school together. There was freedom, but Islam was still a part of daily life. So there was a wonderful blend of tradition and freedom.”

Shortly after his arrival to the states, AG started Afghan Roofing Company in downtown Raleigh. He began to build himself a community of Afghanis in the state that came together for not only dinners and celebrations, but also to protest, specifically after the Soviet invasion. AG and his friends started an organization called Americans for Permanent Peace in Afghanistan. Tahe’s mother would encourage her to come to the protests, but as a child, Tahe rarely saw the point. Now, she understands the importance of speaking out.

“I remember going shopping and my mom sewing curtains, doing all this stuff to make a new home for them,” Tahe said. “When they came over, it was February of 1981 and I remember my dad coming in in the middle of the night and waking me and my sister, saying we had to go to the airport to pick everybody up.

“It took me well into adulthood to see how different my life was,” she continued. “I had a cozy bed in a safe place, yet here’s my dad’s family coming to a new place carrying only the things they could carry, leaving their home behind. When they got here, you would never know the sadness or the fear or anything. They embraced this new life, and they’ve been here ever since.”

Tahe’s uncle and cousins were the last of the family still in Afghanistan up until recently. Her uncle had lived in Germany for several years and married a woman in Pakistan before moving back to Afghanistan. They have five adult children, all of whom recently escaped back into Pakistan. Tahe has never met them.

Several of Tahe’s aunts were able to visit in the late ’90s or early 2000s, and her eldest aunt, Khadija, was able to visit more recently. But now, they are focused on getting her cousins out of the country, especially the women.

All over Afghanistan, women are afraid to leave their homes for fear that the Taliban will stop them. The Taliban says women should not leave home without a man to chaperone them. CNN reported on a rickshaw driver in Kunduz who was physically assaulted for transporting a woman who was traveling without a chaperone.

“I’d always hoped to visit Afghanistan someday,” Tahe said. “I’m 46. You never know, but I’ve kind of given up that dream, but I still hope my son, who’s 15, will be able to visit.”

Mariam Stephan, Greensboro, 49

Mariam Stephan’s memories of Afghanistan are peaceful, illuminated by childhood and the fact that more than 40 years of conflict had not yet torn her mother’s birth country to pieces.

Mariam’s family lived in Afghanistan for a year, in 1978. Shortly after, the Soviet Union took over.

“The ’60s in Kabul were incredibly advanced,” Mariam said. “My mom went to Germany to study abroad and met my father in Hamburg. They married there and came to the states in 1969. She was the first in the family to travel and move abroad, but that started to happen more from the early ’70s through the mid-’80s.”

Her mother, who was born and raised in Kabul, grew up with seven brothers and one sister. Some of them had been forced to flee when the US invaded, them having worked for the Russian government. Most of them now live in the US and Canada. But two of Miriam’s uncles are still in Kabul with their families.

“Right now the concern is that they both have daughters who were either working as professionals or in college, and all of that stuff right now is terrifyingly put on pause,” Mariam said. “Everything is in limbo. They’re hiding in the house and everyone is just waiting.”

Mariam’s mother has passed away, but two of her uncles in California are in touch with their family in Kabul. Mariam’s aunt is in Istanbul and is trying to get her visa to the US.

“Thank God that she’s not in Afghanistan,” Mariam said. “But we’re feeling really helpless and angry about the loss of freedom and support for my cousins in Kabul right now.”

One of the biggest losses for Mariam’s family is the loss of what Afghanistan once was. Mariam recalls that not only was the country physically beautiful, but she remembers the people.

“They just want a beautiful, peaceful life with their family, just like here,” Mariam said. “The people there have tried to hold onto culture and tradition without losing sight of other people’s demands of them. People’s homes and right to live a decent life on their own terms have just disappeared. I’d just want everyone here to contemplate what that would be like and how infuriated you would become if someone suddenly came in and occupied your neighborhood, terrorized you.

“I’m very fortunate,” she said. “I’ve been here my whole life and my sense of loss or dislocation to the country and my mother’s homeland, I feel like it’s such an abstract sense of loss and pain, but it’s a sense that gets heightened now. There’s a helplessness. I knew I would never be able to go back anyway, but it becomes all the more poignant now. Any remnant of reclaiming connection to the land and the beauty of that place is further away from me.”

When Mariam was a child, so few Americans she knew had even heard of Afghanistan, and it saddens her to know that this is how people think of it, as war-torn. Even now, the people she knows only seem to care about Afghanistan when it is in the news.

“The wars and struggles in Afghanistan have been going on for so long, and people only seem to care when it’s fashionable,” she said. “But even 20 years ago when Bush invaded, I realized they’d never be able to leave. It was shocking that this was going to happen. This is the inevitable conclusion when you look at that kind of guerrilla warfare.

“Everyone, regardless of political party, would agree that Americans have a short-term memory,” she continued. “Unless you’re directly involved, something like Afghanistan in particular has such a complicated history. So many hands have tried to take control of it. Everyone from Reagan forward is complicit in cultivating the tragedies that are unfolding now.”

Mustafa, Tahe and Mariam are encouraging the American government to help the people of Afghanistan. The North Carolina Senate can be called at 919-733-4111 or sent letters at 16 W. Jones St., Raleigh, NC 27601

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply