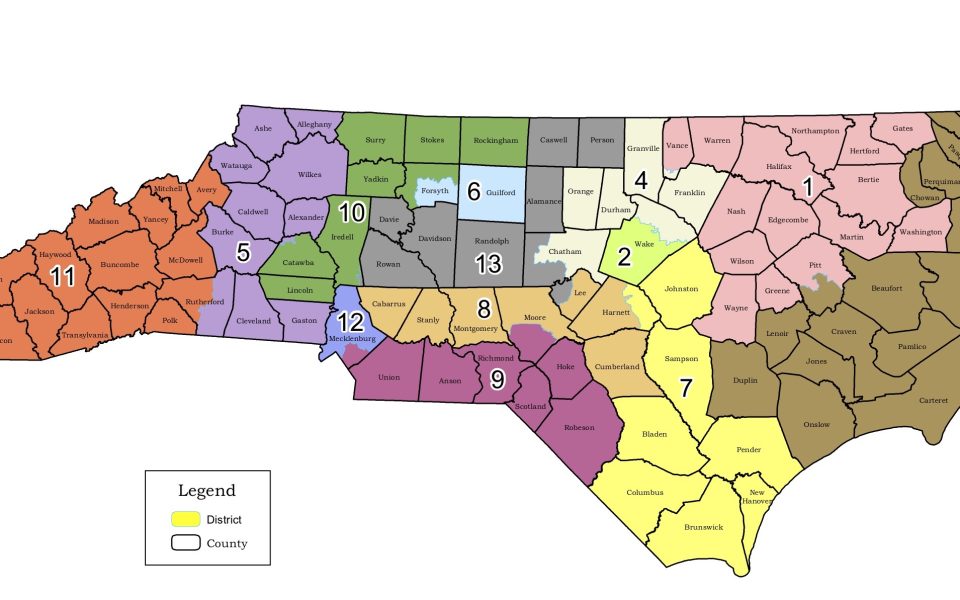

As an illustration of how North Carolina Republicans have cynically manipulated race to maintain political power, it’s hard to imagine a starker example than the line drawn right down the center of NC A&T University, splitting the largest HBCU in the country in two while ensuring that Republicans would hold two congressional districts carved out of Guilford County.

The split was the subject of a short documentary produced by Now This News, released on the eve of the 2018 midterm elections, with 314,700 views to date. Common Cause NC fielded an organizer to mobilize students around the issue. NBC News, Vox and the Grio all published stories, and former Attorney General Eric Holder visited the university to highlight the split.

Under a court order finding the congressional district maps to be an impermissible partisan gerrymander, Republican lawmakers in Raleigh approved a remedial plan last week that does indeed remedy this particular grievance.

The new map — a one-off for the 2020 election before the next round of mapmaking in 2021 based on the next US Census — consolidates Greensboro, Winston-Salem and High Point into a new, compact 6th District and likewise puts most of Wake County into a new, urban 2nd District.

Merging the Triad cities into one congressional district makes sense on a lot of levels. Only two weeks ago, I used this space to note the absurdity that the two ultra-conservative lawmakers who represent Guilford County are attacking the impeachment process, which is presumably supported by a majority of their constituents in this Democratic-leaning county.

So, all good, right?

The short answer is no. The new map passed on strict party-line vote with no support from Democratic state lawmakers. A lawsuit filed on the same day the bill was ratified describes the remedial plan as “another extreme and obvious partisan gerrymander that violates the constitutional rights of North Carolina voters.”

The new map amounts to an 8-5 partisan gerrymander, allowing Democrats to pick up two seats in addition to the three that they currently hold. “We need a 6-7 map, or a 7-6 map, or a 6-6-1 map,” Rep. GK Butterfield (D-NC) told Politico. “Those would be fair maps.”

The mixed review of the remedial plan reveals the tension between two districting criteria — preservation of communities of interest and proportionality. Preserving a community of interest — for example, placing two cities that share an airport, a major road system and potentially a future commuter rail link — in the same district is a traditional districting principle, although in practice it’s often been sacrificed for the sake of preserving political divisions like counties and protecting incumbents. Proportionality — drawing districts so that the partisan balance reflects recent statewide election results — is actually not a principle in current use, although Ohio has adopted it beginning in 2021, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

I spoke with two local Democratic politicians, both of whom acknowledged a benefit to consolidating urban voters in the Triad and Wake County, while still contending that the maps need to be fairer.

-

Rep. Pricey Harrison, a Guilford County Democrat, voted against the map. (file photo) -

Dan Besse, a Winston-Salem City Council member who is running for state House in Forsyth County, said Winston-Salem and Greensboro are better off being represented by a Democrat in Congress. (file photo)

“I think it’s super important that Greensboro, Winston-Salem and much of Wake County will have Democratic representation,” said Rep. Pricey Harrison, a Guilford County Democrat who voted against the map. “That’s an improvement you can’t discount. [But] it could have been a fairer map.”

Dan Besse, a Winston-Salem City Council member who is running for state House in Forsyth County, said Winston-Salem and Greensboro are better off being represented by a Democrat in Congress, particularly when Democrats hold control of the chamber.

“In terms of transportation interests, certainly I am going to feel like I have a better chance to get the attention we need for public transit, and other non-highway interests included in our mix with any mainstream Democrat as opposed to the current Republican representatives,” he said.

The bitter pill for Democrats in evenly divided states like North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin is that their voters are clustered in urban areas while Republican voters are more spread out.

“The fact that in North Carolina, as in most states, people who choose to live in urban areas are more likely to lean toward progressive policies and therefore in today’s environment support Democrats than the sort of more deeply rural areas does make it more challenging to draw districts that are both compact and competitive,” Besse said. “If you put a heavy premium on compactness over competitiveness, then you do kind of exaggerate a Republican lean.”

Besse is a student of politics who can appreciate the structural underpinnings of the system, but he’s also a politician who is optimistic by nature.

“It ought to be possible to draw a number of competitive districts that are reasonably compact and have a party balance more open to the voters in the general election than you find under either the existing map or the one being redrawn,” he insisted.

Michael Bitzer, a political science and history professor at Catawba College, expressed skepticism.

“How are you defining competitive?” he asked. “Six districts Democratic and six districts Republican, and one competitive? Are you talking about all 13? If that’s the case, you’re fighting against what you call political geography. Some counties will vote for one party 60 percent or greater. There are just some practical realities of voter behavior that you can’t go around.”

So, are urban, progressive voters doomed to perpetual under-representation?

“By concentrating themselves into very compact areas, Democrats have done it to themselves, for lack of a better term,” Bitzer said. “It’s nobody’s fault other than where people choose to live. People are sorting themselves into likeminded communities, and those communities are going to vote in very sorted ways, and that’s just the nature of how Americans are choosing to politically isolate themselves. Some would describe it as political segregation.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply