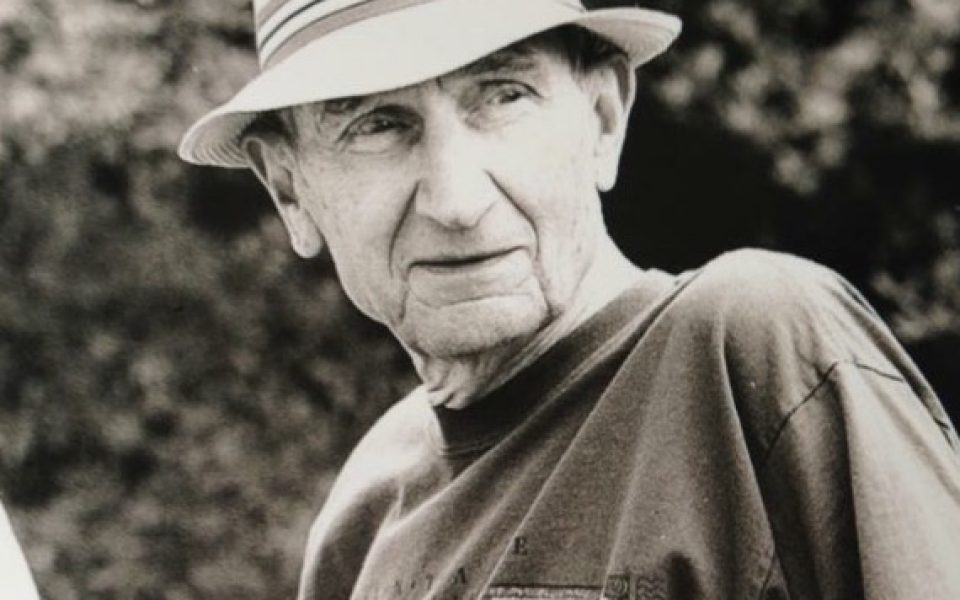

The Rev. Zeb North Holler Jr. was a Jesus follower. I’m having difficulty at the moment thinking of anyone who more fully lived in to that noble yet humble calling.

I first encountered Holler, who died on Dec. 8 at the age of 88, as a speaker at Government Plaza in downtown Greensboro at the culmination of a march from the site of the former Morningside Homes to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the 1979 Klan-Nazi massacre. This is a paraphrase, but I recall Z — as he was known to everyone — essentially saying that we should be able to agree that a society where all people are valued and treated with respect is a worthy goal. His words have stayed with me over the past 12 years as an essential truth, both as a statement of first political principles and moral values.

In the context of the Greensboro Truth & Reconciliation Project, which Z helped launch, these words could be taken as both a salve to the suffering and a challenge to political establishment and authority. If a society where all people are valued and treated with respect is a worthy goal, then how does one accept that five people organizing to improve the lives of low-income millworkers could be extinguished without adequate police protection, and that their killers could be acquitted in a court of law when their crime was committed in broad daylight and captured by television cameras? How is it possible for public opinion to be manipulated towards the cause of demonizing the victims rather than addressing the root cause of inequality that produced the violence?

These are radical questions, and Z’s life reminds me that Jesus’ ministry was geared towards building a community that welcomed outcasts and the poor, and also reminds me that practicing authentic solidarity with those who are shut out of the power structure often requires a willingness to sacrifice prestige and wealth.

By the time I got to know Z — long after he had officially retired as a pastor — he had become something of a beneficent elder. He was not the principal organizer or the most visible orator, but rather an encouraging presence at truth and reconciliation gatherings, press conferences to highlight discrimination against black police officers, and meetings to grapple with allegations of police misconduct against civilians. I will always think of Z — along with his wife, Charlene — as a friend because he consistently greeted me with a wide smile and asked with genuine interest how I was doing. Once, he asked me for feedback on a collection of essays that he wrote about scriptural teachings, while also seeking references to other young people who could help him hone his message.

Z was a white Southern pastor and World War II veteran who didn’t hesitate to take a stand for racial justice when it was dangerous and unpopular to do so — in other words, when it counted. As a young pastor, he hosted the freedom riders in Anderson, SC in 1960, ignoring a threat from the Ku Klux Klan, and later, in 1968, his church in Atlanta fed thousands of people who came to mourn the death of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. In 1979, just two months after becoming the pastor of Presbyterian Church of the Covenant in Greensboro, he rode in the lead hearse of the cortege for the five people killed in the Klan-Nazi massacre so that he could lend moral support to the funeral director, who had expressed reservations about taking the bodies because of fear of violence.

The Rev. Nelson Johnson, whose friends were killed in the massacre, recalled during a memorial service on Sunday how he had met with a group of white pastors shortly after he was unjustly jailed in the aftermath of the atrocity. One of them was Z, who asked him a serious of questions.

“Here was a white man that treated me with respect and who landed a plane on an aircraft carrier in World War II,” Johnson recalled. “That stood out to me.”

They went on to co-found the Beloved Community Center, an interracial activist center in Greensboro that took as its inspiration King’s call for a “beloved community” — a translation of the theological concept of “the kingdom of God.”

As Z’s health was declining, Johnson said he would often say during visits: “Nelson, we’re good friends.” Explaining during the memorial service that his life has been shaped by race and racism, Johnson said that he would respond in all sincerity: “Z, you’re my best white friend.”

On their last visit, a couple weeks ago, Z told Johnson: “Nelson, we are good friends, good friends.”

This time, Johnson’s response was different.

“I didn’t say, ‘Z, you are the best white friend that I have,’” Johnson said. “I told him: ‘I want you to know that you are among the best friends that I have and that I ever expect to have.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply