On Jan. 12, Triad City Beat published a story in which Brian Ricciardi, the owner of Dom’s and Radici — the Triad’s only full-service vegan restaurants — explained his analysis of how and why his businesses closed.

He talked about inconsistent employees who asked for too much pay, a lack of respect for the food industry and his own refusal to change his vision as the reasons why he closed both locations in August 2022. Now, former employees are speaking out to tell their side.

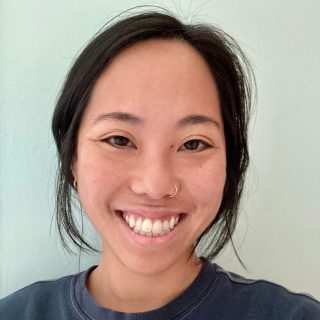

“He framed himself as a noble and valiant man against the world and didn’t acknowledge anything else that happened,” said Catherine Lupien, a former Radici employee.

In a series of conversations, TCB spoke with six former Dom’s and Radici employees who said that lack of consistent pay, clear communication and a general lack of Ricciardi’s presence were the real reasons why his businesses failed.

“I cannot say in strong enough terms that Brian was such an absent owner in that restaurant,” said Katie Lowe who worked at Radici from late May-July 2022. “And then to turn around and blame the servers for having bad attitudes, he wouldn’t even know; he wasn’t there.”

As noted in the former piece, Ricciardi closed both locations in August 2022 and reopened just Dom’s in Winston-Salem a few months later. Now, he’s running the operation by himself using a takeout-only model. Throughout his conversation with TCB he talked about how he didn’t want to just “hire a warm body” and that he was fine doing things on his own if it meant he didn’t have to deal with other people’s issues.

“I’m not dealing with that again; I don’t need anybody,” he said. “If I go back to that, I will close again and I will stay closed and I will wash my hands of this industry.”

But employees who spoke to TCB said that the reason why people don’t want to work for him anymore is because of the way he treats them. Chief among their complaints were consistent accusations of low pay.

“I would say that in terms of wages and work, Dom’s is the least paid job that I’ve had in my life,” said Kyle Govan, who worked as a bartender at Dom’s from August-October 2021. “And I worked in high school.”

Issues with pay

Former servers and bartenders for both locations said that they made the state minimum wage for serving, which is $2.13. That’s not unusual throughout the industry because of the understanding that most servers’ pay comes in the form of tips. But even that was confusing at Ricciardi’s businesses, employees said.

Govan said that as a bartender, he was paid the minimum wage. He worked between 30-40 hours per week but most of that time was spent doing what Govan considered kitchen work.

“I was juicing stuff and preparing things that would go in the drinks,” Govan said.

And while Ricciardi said that juicing fruit for cocktails makes sense as part of the bartender’s job, Govan said it wasn’t financially sustainable because he spent most of his lunch shift prepping but not getting tips because customers didn’t order drinks during the day.

“I spent half of my week just juicing stuff,” Govan said. “I wouldn’t make any money at lunch.”

Kaylyn Snitzel, who also worked at Dom’s as a bartender from June-November 2021, supported Govan’s account.

“During the lunch shift I was doing a lot of prepping,” she said. “I wasn’t getting tipped during that time because the bar was really slow.”

After working 75 hours across two weeks, Govan said his paycheck came to about $400. That amounts to a $5.33 hourly wage. After working about 80 hours, Schnitzel said her paychecks would be about $500 or $6.25 per hour.

When asked about the low wages, Ricciardi said that none of his bartenders made $2.13 per hour. He also said that prep work is part of the job and if it’s slow, that’s just how it is.

“You’re prepping for when it will be busy,” he said. “That comes along with the job of being a bartender. To say you deserve $10 an hour because you’re doing a case of limes, you’re on shift.”

According to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median hourly wage for servers in the US was $12.50/hour in May 2021. That rate includes tips. Based on their data, the lowest 10 percent earned less than $8.58, and the highest 10 percent earned more than $22.07.

Lupien, who worked at Radici from January-July 2022, said that earning such low wages on South Elm Street in downtown Greensboro was discouraging.

“People down the street were making $5 plus tip share,” she said.

Snitzel, the former Dom’s bartender, said that when she was hired on, she was told that tips from online orders would be added to her paycheck. Then she found out that they actually went to the restaurant.

Kaleb Denny, who was hired as a host at Dom’s in October 2021, was also told by a manager that he would be paid $12/hour plus tips from to-go orders. But he said that didn’t happen.

“We would get told one thing but we weren’t sure what the tips were or where they were coming from,” he said. “I know just that it wasn’t reflecting on my check.”

And that’s if he got paid at all.

Several employees who spoke to TCB claimed that pay was late on more than one occasion. Denny said that he didn’t get his first paycheck via direct deposit so Ricciardi, who handled payroll, had to write him a paper check.

“This happened on multiple occasions with people,” Denny said.

Lupien said that during her six-month tenure, Ricciardi forgot to do payroll about four or five times. Once, checks were almost three weeks late, she said.

“He would forget to submit it once a month or so on time,” Lupien said. “He would have to write us paper checks, but the problem was that it took forever to get in touch with him or have him come to Radici. We didn’t know when we could get our checks.”

Lowe, who worked at Radici, supported Lupien’s claim.

“It was consistently not on time,” she said. “We were told we got paid on Friday but then a weekend would pass and we still wouldn’t get paid. We were frustrated because many people timed their bills on when their paycheck was going to come in.”

When asked about the issues with pay, Ricciardi said that he has never been late on payroll.

“Have I had to write paper checks before? Yes, because sometimes I’ve had issues with the payroll service,” he said. “But payday was every other Tuesday at 5 p.m. Nobody was never not paid on time.”

Ricciardi also said that he knew that his employees had bills to pay.

“I have a really big thing about people negatively affecting other people,”he said. “So something like pay that I have control over? Hell no, I know you have rent due; that’s on my mind, I’m not built that way.”

As for the confusion with tips, Ricciardi said that the pooled system was what he used to create a sense of camaraderie between employees.

“Ultimately we were trying to create this team environment in which everyone is together,” he said. “It’s not just my tables and my section, we should all care about this equally.”

And that feeling of camaraderie was felt by many of the employees that spoke to TCB, but broke down, they said, because of Ricciardi’s lack of consistency.

An absent owner

When she first started working at Radici in January 2022, Lupien said she loved it.

“The very beginning of it, the training and the serving for several months was really, really beautiful,” she said. “All of the servers, it was always a really great camaraderie and a great space…. For a while it was a place of peace.”

Her relationship with the manager and the chef was clear and supportive which was important, Lupien said, because Ricciardi was never there.

“Brian was not involved in our management,” she said. “I probably met him like 10 times.”

Lowe, who also loved working at Radici in the beginning, said Ricciardi’s absence was a problem.

“He came in about once or twice a week in the evenings,” she said. “He would come in and sit at the bar and eat and drink, usually with a friend. I never got to know him.”

Sometimes Ricciardi would come in with his girlfriend who took pictures of the food for the website and social media, and would order food and stay past closing, Lowe said.

“He would come in and order a lot of food,” she said. “And the expectation was that you did not leave until every single dish was cleaned, so it was like employees in the back couldn’t go until Brian left and his dishes could be cleaned. I would leave before he left, if I was closing. I would leave as late as 10:30 or 11 p.m. and he would still be there.”

Ricciardi refutes this claim as well.

“I never asked people to make me food past closing,” he said. “I never put anyone in any position that I was demanding special treatment, hell no.”

Ricciardi does concede that he was absent from his businesses at times.

“That is why I hire managers,” he said. “That is their role; that is their place.”

And if he was absent, it was so he could give his staff space to be creative, he said.

“That’s part of the problem,” Ricciardi said. “You give people a certain amount of freedom, creative freedom, and sometimes that comes back to bite you. They’ll say, ‘Well there never was clear cut direction.’ Well, there isn’t going to be, because I’m giving you freedom.”

But that freedom didn’t translate to letting staff be creative, some employees said.

Shane Young started working at Dom’s around March 2021. He knew Ricciardi prior to applying because he was a regular at Mozzarella Fellas, Ricciardi’s first restaurant. As a vegan, he was inspired by Ricciardi’s passion for plant-based food and told him that he’d do anything to help his business thrive.

He started as a dishwasher. Then he worked up to the food line doing prep. While he was there, Young said he worked under the head chef who had gone to culinary school and would bring ideas to Ricciardi about the menu. But more often than not, he would shut them down.

“He wanted us to be in charge of everything, but whenever we had ideas like the chef was wanting to do a particular thing, [Brian] didn’t see it, or it wasn’t the direction he wanted to go,” Young said.

Govan, the bartender from Dom’s, said that he would bring Ricciardi ideas for new cocktails but that he wouldn’t take them into account.

“It was like ‘We are being creative, but you’re not listening to us,’” he said.

Ricciardi pushed back and said that most of the time, he would say yes to new ideas.

“I think I was a very open person,” he said. “I would generally say I’m a ‘Yes man’ to a majority of things. I would say, ‘Sure let’s try it.’”

Denny, the former host at Dom’s who eventually worked up to assistant manager, remembered a time when he brought the idea to have a coffee menu at Dom’s to Ricciardi. One day when he came into work, Denny noticed that Ricciardi had bought an espresso machine “out of nowhere.”

“I said, ‘I’m happy you took my idea, but I need help with executing it and training,’” he said. “He said, ‘Well that’s your task, you have to figure it out.’ He just wanted people to give ideas but he would be mad at you if you weren’t able to execute it.”

On another occasion, Young remembered Ricciardi watching over the chefs make plates in the kitchen when he started criticizing the lack of effort they were putting forth.

“He said, ‘Why aren’t you putting any heart into it?’” Young recalled. “And I thought, You’re not the one here. You’re not the one sitting over this stove so why are you telling me that I’m not putting any heart into it?”

Despite Ricciardi’s absence many of the employees were passionate about their work, Lupien said.

As a server at Radici, she said they went through a lot of training and studied the wines, the food and how different ingredients worked together so they could knowledgeably answer if customers asked questions.

“I put a lot of effort into my job so I could be passionate about what I was selling,” she said.

But the demands by Ricciardi and the inconsistencies with the menus led to employee burnout.

Inconsistent menus

Radici, when it opened after Dom’s, was advertised as an upscale, small-plate, vegetable-focused restaurant that would serve seasonal dishes. In the beginning the menus were creative but when the head chef at Radici was forced to cook at Dom’s because of staff shortages, the menu stagnated.

“Our regulars started to notice,” Lupien said. “They asked, ‘Oh, when’s the menu going to change?’ We had to give a bullshit answer to pacify them because we had no idea when it was going to change.”

Over at Dom’s the issue was reversed.

Young, who worked in the kitchen at Dom’s said that Ricciardi changed the menu fairly often.

“It was inconsistent,” he said.

Snitzel, who worked as a server at Dom’s, said that made her and other front-of-house employees’ jobs even more difficult.

“We were falling apart; we needed him there,” she said. “We needed him to figure out what the hell was going on with the menu. It was never consistent. Sometimes we had customers who really liked a dish and we would have to tell them, ‘We don’t have that anymore.’”

The issue, employees said, came down to a lack of clear communication.

One time Young said he came into a shift and learned that there was going to be a 70-person reservation that day.

“It was so hectic,” he said. “We were still running full capacity on the other side of the restaurant and having the full menu while also trying to satisfy this party of 70.”

While kitchen staff usually doesn’t get tips, that shift Young asked for a cut for his efforts.

“We didn’t get it until four weeks later,” he said. “The worst part about it was that it was like $50. Our efforts were not appreciated.”

Ricciardi said he doesn’t remember that exact event but said there were multiple large-party events at Dom’s.

Quitting time

As time went on, more and more employees started to leave.

In February 2022, Young, who was making $12 per hour, was facing eviction from his apartment after losing a roommate. He texted Ricciardi for an advance on his paycheck but got no response. After almost a year of working at Dom’s, he quit.

“I left because I feel like my worth is more than what Brian wants to give,” he said. Young now works in IT.

Others left after just a few months.

Former Dom’s bartender Kyle Govan, who now works on a food truck, left after three months. Kaleb Denny and Kaylyn Snitzel left Dom’s after four. Denny now works at Starbucks while Snitzel works for a human-capital management company. Catherine Lupien left Radici after seven months and now teaches music lessons from home. Katie Lowe, who now works in a museum, left after just two months.

This issue of a high turnover rate is not, of course, a problem unique to Ricciardi’s businesses. According to a study by 7shifts, a restaurant scheduling company that looked at restaurant data from August 2021-August 2022, the average employee tenure in a restaurant is just 110 days, or a little more than three months. According to the same study, there was about a 55 percent turnover rate for restaurant employees who started in December 2021. According to Bureau of Labor data from November 2021, the quit rate for the food industry rose from 4.8 percent to close to 7 percent in just one year. Additional data analyzed by the National Restaurant Association found that “during the 6-month period between October 2021 and March 2022, unfilled job openings in the hospitality sector exceeded total hires by an average of 500,000 each month.” And that’s due to a lot of issues within the industry including low wages, long hours, difficult work environment and in the worst cases, sexual harassment or assault.

Now, as he tries to run Dom’s alone, Ricciardi admits that he’s a difficult person to work for.

“A thousand percent,” he said. “I’m so specific. I have this almost unrealistic expectation and I know that. I think that’s why I’ve achieved certain things in my life but I know the difficulty that can bring…. I have my stuff. I’m not perfect, but I care about treating people well.”

But that’s where he fell short, according to his past employees.

“I hope this is a wake-up call for him that he needs to treat people with respect and dignity rather than taking advantage of people’s time and loyalty and people who respect the vegan vision,” Denny said. “He really sought out this vegan concept that people really wanted to be a part of.”

Other employees told TCB that it felt like Ricciardi weaponized his vision and his passion for the vegan businesses to succeed.

“He would always be like, ‘Be here for the vision,’ but what’s the vision if I’m not making money and we’re not growing and you’re not here?” Snitzel said.

Because many of the employees were vegan, they wanted the restaurants to succeed.

“We wanted to carry on this idea because we believed in it,” Govan said. “It wasn’t like we didn’t care about the food or the restaurant or the idea. We wanted him to be successful because we have the same ideals that the restaurant does.”

Looking back, the employees express a kind of sadness about what could have been.

“I think it’s sad that the only fully vegan restaurant in Winston-Salem is in his hands,” Young said. “I think that’s the sad part, but we tried to make it work the best we could.”

Join the First Amendment Society, a membership that goes directly to funding TCB‘s newsroom.

We believe that reporting can save the world.

The TCB First Amendment Society recognizes the vital role of a free, unfettered press with a bundling of local experiences designed to build community, and unique engagements with our newsroom that will help you understand, and shape, local journalism’s critical role in uplifting the people in our cities.

All revenue goes directly into the newsroom as reporters’ salaries and freelance commissions.

Leave a Reply